Office of Economic Policy

U.S. Department of the Treasury

Non-compete Contracts: Economic Effects and Policy

Implications

March 2016

2

Table of Contents

Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 3

Section I. Non-competes and Their Justifications ................................................................................... 6

Section II. What Can We Say About the Justifications? ...................................................................... 11

Section III. The Details of Non-compete Enforcement ......................................................................... 14

Section IV. Effects of Non-compete Enforcement ................................................................................. 18

Section V. Directions for Reform ............................................................................................................ 24

Appendix A ............................................................................................................................................... 27

Appendix B ............................................................................................................................................... 32

Works Cited .............................................................................................................................................. 34

3

Executive Summary

Non-compete agreements are contracts between workers and firms that delay employees’ ability

to work for competing firms. Employers use these agreements for a variety of reasons: they can

protect trade secrets, reduce labor turnover, impose costs on competing firms, and improve

employer leverage in future negotiations with workers. However, many of these benefits come

at the expense of workers and the broader economy. Recent research suggests that a

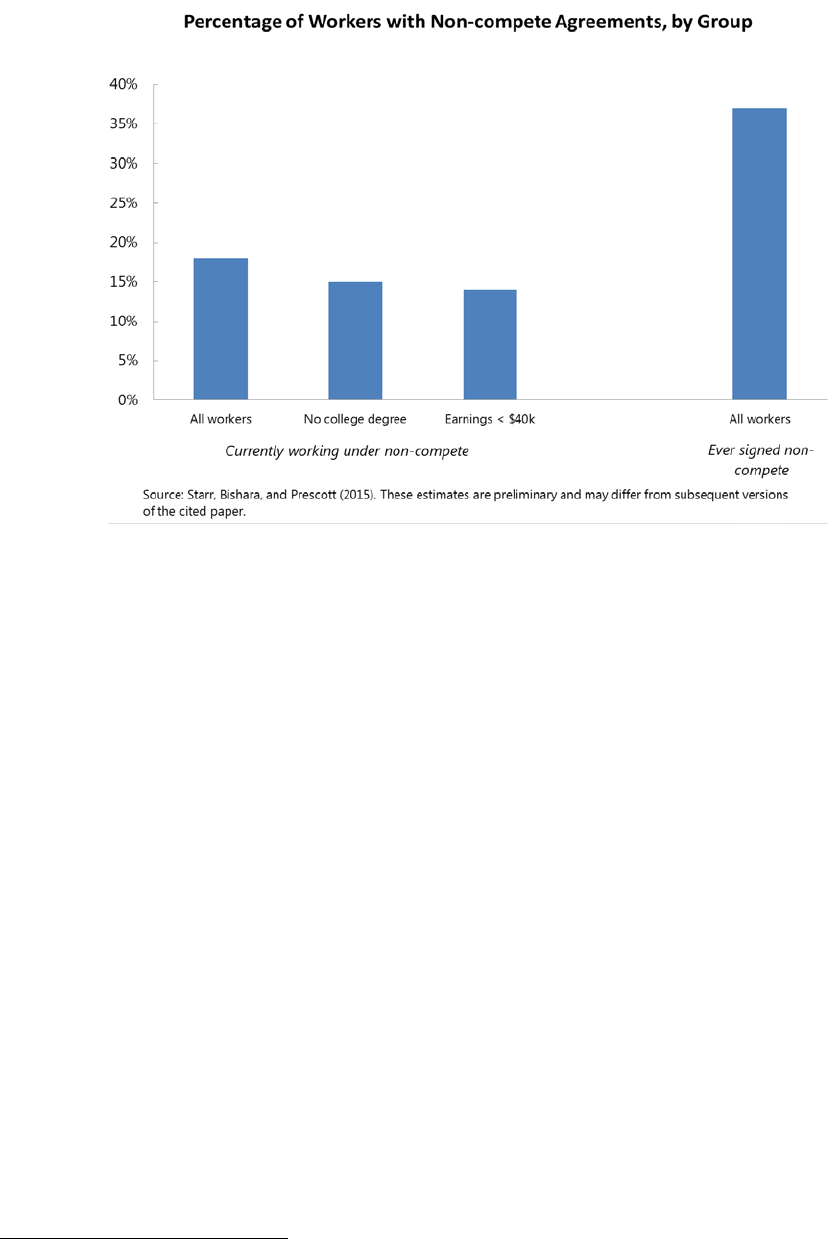

considerable number of American workers (18 percent of all workers, or nearly 30 million

people) are covered by non-compete agreements.

1

The prevalence of such agreements raises

important questions about how they affect worker welfare, job mobility, business dynamics, and

economic growth more generally. This report presents insights from economic theory and

evidence on the economic effects of non-compete agreements. It goes on to discuss policy

implications, starting a discussion about how such agreements could be used in a way that

balances the interests of firms with those of workers and society as a whole.

Non-compete agreements have social benefits in some situations.

• Non-competes are sometimes used to protect trade secrets, which can promote

innovation.

• By reducing the probability of worker exit, non-competes may increase employers’

incentives to provide costly training.

• Employers with especially high turnover costs could use non-competes to match with

workers who have a low desire to switch jobs in the future.

But non-compete agreements can also impose large costs on workers.

• Worker bargaining power is reduced after a non-compete is signed, possibly leading to

lower wages.

• Non-competes sometimes induce workers to leave their occupations entirely, foregoing

accumulated training and experience in their fields.

1

These and other similar numbers throughout the executive summary and report are from Starr, Bishara, and

Prescott (2015) and private correspondence with the authors. Note that all figures are preliminary and may change

slightly.

4

• Reduced job churn caused by non-competes is itself a concern for the U.S. economy. Job

churn helps to raise labor productivity by achieving a better matching of workers and

firms, and may facilitate the development of industrial clusters like Silicon Valley.

Moreover, there is reason to believe that many specific instances of non-compete

agreements are less likely to produce social benefits.

• Non-competes are often used by employers in non-transparent ways:

o Many workers do not realize when they accept a job that they have signed a non-

compete, or they do not understand its implications.

o Many workers are asked to sign a non-compete only after accepting a job offer.

One lower-bound estimate is that 37 percent of workers are in this position.

o Many firms ask workers to sign non-competes that are entirely or partly

unenforceable in certain jurisdictions, suggesting that firms may be relying on a

lack of worker knowledge. For instance, California workers are bound by non-

competes at a rate slightly higher than the national average (19 percent), despite

the fact that, with limited exceptions, non-competes are not enforced in that state.

2

• Only 24 percent of workers report that they possess trade secrets. Moreover, less than

half of workers who have non-competes also report possessing trade secrets, suggesting

that trade secrets cannot explain the majority of non-compete activity.

• Non-competes are common among workers who report lower rates of trade secret

possession: 15 percent of workers without a four-year college degree are subject to non-

competes, and 14 percent of workers earning less than $40,000 have non-competes. This

is true even though workers without four-year degrees are half as likely to possess trade

secrets as those with four-year degrees, and workers earning less than $40,000 possess

trade secrets at less than half the rate of their higher-earning counterparts.

• Available evidence suggests that workers with a low initial desire to switch jobs are not

more likely to match with employers who require non-competes.

• In some cases, non-competes prevent workers from finding new employment even after

being fired without cause; in such cases, it is difficult to believe that non-competes yield

social benefits.

2

Depending on the facts of the individual case, such non-competes may be enforced in other states.

5

States vary greatly in the manner and degree to which they will enforce non-competes.

• In some states, non-compete enforcement is determined by statute, while in others it is

determined exclusively by case law.

• Some states refuse to enforce non-competes, or refuse to enforce non-competes that

contain any unenforceable provisions (“red-pencil” doctrine), although a majority of

states will modify overbroad non-compete contracts to render them enforceable (“blue-

pencil” and “equitable reform” doctrines).

The analysis in this report suggests several broad recommendations that would minimize

the harms associated with non-compete agreements.

• Increase transparency in the offering of non-competes.

• Encourage employers to use enforceable non-compete contracts.

• Require that firms provide “consideration” to workers bound by non-compete contracts in

exchange for both signing and abiding by non-competes.

6

I. Non-competes and Their Justifications

3

Non-compete contracts – agreements between workers and firms that restrict workers’ ability to

take new employment – have a long history, but their scope, prevalence, and enforcement have

varied widely across time and place. With the recent development of more comprehensive data

on their usage, it has become more apparent that non-competes are an important labor market

institution meriting careful study. Recent research shows that as many as 30 million workers are

currently covered by non-compete agreements. While in some cases non-compete agreements

can promote innovation, their misuse can benefit firms at the expense of workers and the broader

economy. Details of non-competes and their enforcement have implications for worker

bargaining power, job mobility, and economic growth. This report draws on insights from

economic theory, as well as a rapidly growing body of empirical evidence, to help clarify

thinking about non-competes and non-compete reform.

What are non-competes and who is bound by them?

Many employers ask their employees to sign non-compete agreements. The details of these

contracts vary greatly across firms and states, but they share a common purpose: restricting the

ability of a worker to compete with his or her current employer for some specified period of

time, often in a specified geographic area. Typically, this takes the form of a prohibition on

taking employment at a rival firm, where “rival” may be interpreted quite broadly to include all

firms within a given industry.

Non-compete agreements have become quite common among a variety of types of workers. As

shown in the chart below, roughly 18 percent of workers currently report working under a non-

compete agreement and about 37 percent of workers report having worked under one at some

point during their career. Although such agreements are less common among less-educated

workers and lower-income workers, the fractions of these workers operating under one are still

substantial.

4

3

This report benefited greatly from discussions with Professor Evan Starr, and we are grateful for his time and

expertise. We also make extensive use of Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015). However, the views expressed here

are not necessarily those of Starr and his coauthors, nor are they implicated in any errors.

4

See Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015).

7

How are non-competes typically justified?

The conventional picture of a workplace characterized by non-compete agreements is one that

features trade secrets, including sophisticated technical information and business practices that

firms have a strong interest in protecting. By preventing a worker from taking such secrets to a

firm’s competitors, the non-compete essentially solves a “hold-up” problem: ex ante, both

worker and firm have an interest in sharing vital information, as this raises the worker’s

productivity. But ex post, the worker has an incentive to threaten the firm with divulgence of the

information, raising his or her compensation by some amount equal to or less than the firm’s

valuation of the information. Predicting this state of affairs, the firm is unwilling to share the

information in the first place unless it has some legal recourse like a non-compete contract.

Occasionally, client relationships are included along with trade secrets in this explanation (and

are sometimes treated similarly as a matter of state law). However, it is not clear that

relationships with clients constitute a socially valuable investment analogous to trade secrets.

5

For this reason, trade secrets will be the focus of discussion in this report.

5

For instance, a trade secret involving intellectual property may be the product of expensive investments. If the

investment had not been made, none of the benefits of the property would have been realized. By contrast, the

8

While non-competes help solve the trade secrets “hold-up” problem, they are not the only tool at

employers’ disposal. States generally have laws prohibiting theft or disclosure of trade secrets.

In addition, employers can use compensation schemes that discourage turnover for workers with

trade secret access (e.g., employers may provide additional compensation contingent on the

worker remaining at the firm).

6

We provide further evidence regarding trade secrets later in the

report.

What are other possible explanations?

What might explain the existence of non-competes among workers who are not plausibly

affected by the sort of trade secrets discussed previously? A number of explanations have been

suggested. One possibility (training) – which may coexist with either of the next two

explanations – is that firms and workers use non-competes to encourage more investment in

workers. In general, firms are reluctant to pay for training that improves a worker’s “general”

skills and makes her more valuable to it and other firms alike. Economists usually think of

general training as occurring when workers accept wage cuts to compensate their employer for

its expenses in providing the training.

7

For various practical reasons, however, workers may be

unwilling to pay for training.

8

Non-competes offer an alternative: firms get an assurance that

workers are unlikely to leave for some period of time, allowing the firm to capture more of the

increased productivity from costly training it provides, and workers receive more training than

they otherwise would.

Another possibility (screening) is that non-competes are an attempt by firms to preferentially

hire workers with a low likelihood of departure. Underlying this alternative is the assumption

that firms face substantial costs for hiring and separating with workers.

9

Moreover, it is not

obvious to firms which workers are most likely to exit, and workers cannot credibly assert their

probability of leaving (i.e., all workers will pretend to have a very low probability, as this raises

their perceived value to the firm). By making non-competes a condition of employment, firms

client, and their need for a good or service, presumably exist independently of any investment made by the

employer.

6

See Salop and Salop (1976) for one discussion of such a mechanism.

7

See Becker (1962).

8

For instance, workers may be credit-constrained and unable to finance the training, or workers may have difficulty

observing the quality of the training, rendering them less willing to pay for it.

9

See Hamermesh (1995).

9

reduce the value of the job to those workers who know they are likely to depart. For those

workers who do not expect to leave imminently, the non-compete is less of an imposition. Note

that in order for this explanation to be correct, prospective workers must understand the non-

compete and its implications.

A final explanation (henceforth referred to as lack of salience) is that workers do not pay

attention to non-compete contracts and do not realize how much bargaining power and future

employment flexibility they are foregoing. Only later, when workers consider exiting a firm, do

they become aware of the existence and/or implications of the non-compete agreement.

10

Other

workers may be aware of the non-compete, but only after it is presented to them once they have

accepted a position or started working, and not at the time the job offer was originally extended.

According to this explanation, only employers benefit from the non-compete, as they obtain

increased bargaining power in future wage negotiations, reduced turnover costs, and possible

impairment of rivals’ ability to hire.

How do the different non-compete explanations affect the optimal policy response?

The explanations for non-compete agreements described above have different implications for

the desirability of such agreements. Thinking through these implications helps to shed light on

the appropriate policy response. The first three explanations – trade secrets, training, and

screening – suggest that non-competes can be socially desirable. The last explanation, lack of

salience, suggests that non-competes are socially harmful.

The conventional explanation for non-compete agreements involving protection of trade secrets

is a potentially strong justification for such agreements where it genuinely applies, and where

other devices for protection of employers (like trade secrets law) are not effective. As previously

discussed, non-competes can encourage additional economic activity and broader information

sharing when trade secrets are significant.

The training and screening explanations for non-compete agreements also suggest social

benefits. If worker training is sufficiently enhanced by the availability of non-competes, or if

10

Research in other contexts has found a large role for salience considerations. See Kahneman (2003) for a

discussion of salience as it relates to behavioral economics, and Feldman, Katuscak, and Kawano (2016) for an

example from the tax literature.

10

firms with unusually high separation costs are able to match more appropriately with workers,

both worker and firm are better off. Balanced against these benefits are the social costs

associated with diminished mobility.

The final explanation for non-compete agreements – lack of salience – implies that non-

competes are merely a costly transfer from workers to firms, made possible by workers’ lack of

awareness. According to this explanation, non-competes lead to diminished worker mobility and

a loss of human capital, with no corresponding benefit to society. When workers are legally

prevented from accepting competitors’ offers, those workers have less leverage in wage

negotiations and fewer opportunities to develop their careers outside of their current firm. By

contrast, the firms using non-competes benefit through reduced turnover costs, increased

bargaining power, and denial of valuable employees to competitors.

Constructing ideal policy for non-competes requires determining which explanation is most

relevant for a particular type of worker (i.e., for low-skill service workers vs. high-skill IT

workers), and balancing the trade-offs between non-competes’ benefits and their undesirable

consequences. For instance, low-wage workers may be particularly poorly served by non-

competes due to the lower likelihood that trade secrets are relevant.

However, it is not always easy to distinguish among the different explanations for non-competes,

and several possible reforms are beneficial regardless of the underlying explanation. For

example, measures to improve the salience and transparency of non-competes and non-compete

enforceability are broadly useful and will help to minimize the worst effects of non-competes.

In Section V, some directions for policy reform are described and their reasoning briefly

explained.

11

II. What Can We Say About the Justifications?

Research on non-competes is still at an early stage. However, a recent paper provides

comprehensive data on workers with non-competes, answering many of the most important

questions about these workers.

11

In addition to collecting information on the characteristics of

workers who sign non-competes, this research also examines the extent to which workers with

non-competes actually interact with clients, have access to client-specific information, and work

with trade secrets.

12

This section summarizes the literature examining the different rationales for

non-compete agreements.

Protecting trade secrets. If protection of trade secrets were the main explanation for non-

compete agreements, then one would expect such agreements to be highly concentrated among

workers with advanced education and occupations likely to feature trade secrets.

13,14

However,

the fraction of workers without a four-year college degree reporting a current non-compete

agreement is about 15 percent, only slightly below the 18 percent share for all workers.

15

While

engineering and computer/mathematical occupations have the highest non-compete prevalence at

slightly more than one-third, occupations like personal services and installation and repair also

include many workers with non-competes, at about 18 percent. When entry-level workers at fast

food restaurants are asked to sign two-year non-competes, it becomes less plausible that trade

secrets are always the primary motivation for such agreements.

16

Unsurprisingly, workers who reported access to trade secrets were much more likely to be bound

by a non-compete, with about a 25 percentage point higher probability than those who report no

interaction with clients, no access to client-specific information, and no possession of trade

secrets. The link between client access and non-competes is not as strong: those who report such

11

See Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015).

12

As the authors’ data is collected through an online survey, achieving a representative sample may be challenging.

The authors note, however, that more traditional survey designs face similar difficulties.

13

Note that not all trade secrets are equivalent from an economic perspective. Though the legal definition of trade

secrets embraces a wide variety of private information (e.g., fast-food recipes), some of these examples may not

involve a substantial “hold-up” problem of the kind described above.

14

See Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015) for evidence that occupations and income groups differ substantially in the

degree to which they involve trade secrets.

15

See Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015).

16

See http://www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2014/10/15/does-jimmy-johns-non-compete-clause-for-sandwich-

makers-have-legal-legs/.

12

access (but no trade secrets) have about a 7 percentage point higher probability of a non-

compete. However, less than half of all workers with non-competes report possessing trade

secrets. Together, these findings suggest that the trade secrets explanation is likely part, but not

all, of the story of non-competes.

Encouraging training. Non-compete enforcement is associated with more worker training. Evan

Starr finds that a “one standard deviation increase in a state’s overall enforceability level

increases the probability that the average high litigation occupation receives firm-sponsored

training by 2.4% relative to low litigation occupations.”

17

Interestingly, this work finds that

when states require firms to offer substantial “consideration” along with a non-compete (e.g.,

promotions, training, and higher wages), both training and wage outcomes for workers are

improved.

Facilitating screening. Starr, Bishara, and Prescott have developed data that are directly relevant

to the question of screening by asking their survey respondents how long they expected to work

for their current employer, then comparing the responses of workers who have and have not

signed non-competes. Interestingly, after controlling for various demographic and economic

variables, there is no relationship between expected tenure and likelihood of having signed a

non-compete. This result suggests that screening is not an important part of the non-compete

story.

Exploiting lack of salience. Several pieces of evidence suggest that employers are relying on

workers’ incomplete understanding of non-compete agreements. First, employers often require

that workers sign non-compete agreements even in states that refuse to enforce them. For

example, in California, which (with limited exceptions) does not enforce non-compete

agreements, the fraction of workers currently under a non-compete is 19 percent, which is

slightly higher than the national average.

Second, a separate survey, exclusively focused on members of the Institute of Electrical and

Electronics Engineers, reports that “…barely 3 in 10 workers reported that they were told about

the non-compete in their job offer. In nearly 70% of cases, the worker was asked to sign the

17

See Starr (2015), page 3. “Enforceability level” is defined by Starr to capture all the dimensions of non-compete

enforcement, and “high-litigation” refers to occupations characterized by more legal action related to non-compete

contracts.

13

non-compete after accepting the offer – and, consequently, after having turned down (all) other

offers. Nearly half the time, the non-compete was not presented to employees until or after the

first day at work.”

18

This evidence is especially powerful insofar as it applies to highly-

educated, high-wage workers who might be considered more likely to understand the process

surrounding non-competes. Even in cases where the conventional explanation of trade secrets

has a surface plausibility, firms often delay the presentation of non-competes. This behavior

would not be necessary if non-competes were a mutually-beneficial arrangement.

Finally, Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015) find that only 10 percent of workers with non-

competes report bargaining over their non-compete, with 38 percent of the non-bargainers not

realizing that they could even negotiate.

19

Moreover, workers appear confused as to whether

non-competes are even enforceable in their states. In preliminary work by Starr and coauthors,

workers are shown to be frequently incorrect or unsure as to whether their non-competes are

actually enforceable. Again, this is not consistent with a “perfect information” setting in which

workers knowingly accepted the limitations imposed by non-competes.

18

See Marx and Fleming (2012), page 49.

19

See Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015).

14

III. The Details of Non-compete Enforcement

Non-compete enforcement differs significantly across states. Some relevant terms of art are

defined below.

Non-compete contract: A contract that delays or in some other way restricts a

worker’s ability to compete with a previous employer. Typically this entails restrictions on

future employment.

Consideration: A benefit received by a signatory to a contract. Generally, both

parties must receive consideration in order for a contract to be valid. Consideration commonly

includes property or promises of specific actions. In the case of a non-compete, consideration

may sometimes refer to wage increases, promotions, or continued employment (sometimes

including hiring).

Protectable interests: These are the aspects of an employer-employee

relationship that provide the legal motivation for a non-compete agreement. They vary state to

state, but frequently include trade secrets, confidential information, goodwill, and/or client

relationships. Some states additionally provide protection for special training.

Red-pencil doctrine: Doctrine prevailing in some states requiring that courts

must declare an entire non-compete contract void if one or more of its provisions are found to be

defective under state law or precedent.

Blue-pencil doctrine: Doctrine prevailing in some states requiring that courts

delete provisions of a non-compete contract that render it overbroad or otherwise defective,

retaining the enforceable subset of the contract.

Equitable reform, aka Reformation: Doctrine prevailing in some states

requiring that courts may rewrite a non-compete contract so as to render it non-defective. Unlike

blue-pencil doctrine, this may entail insertions of new text.

15

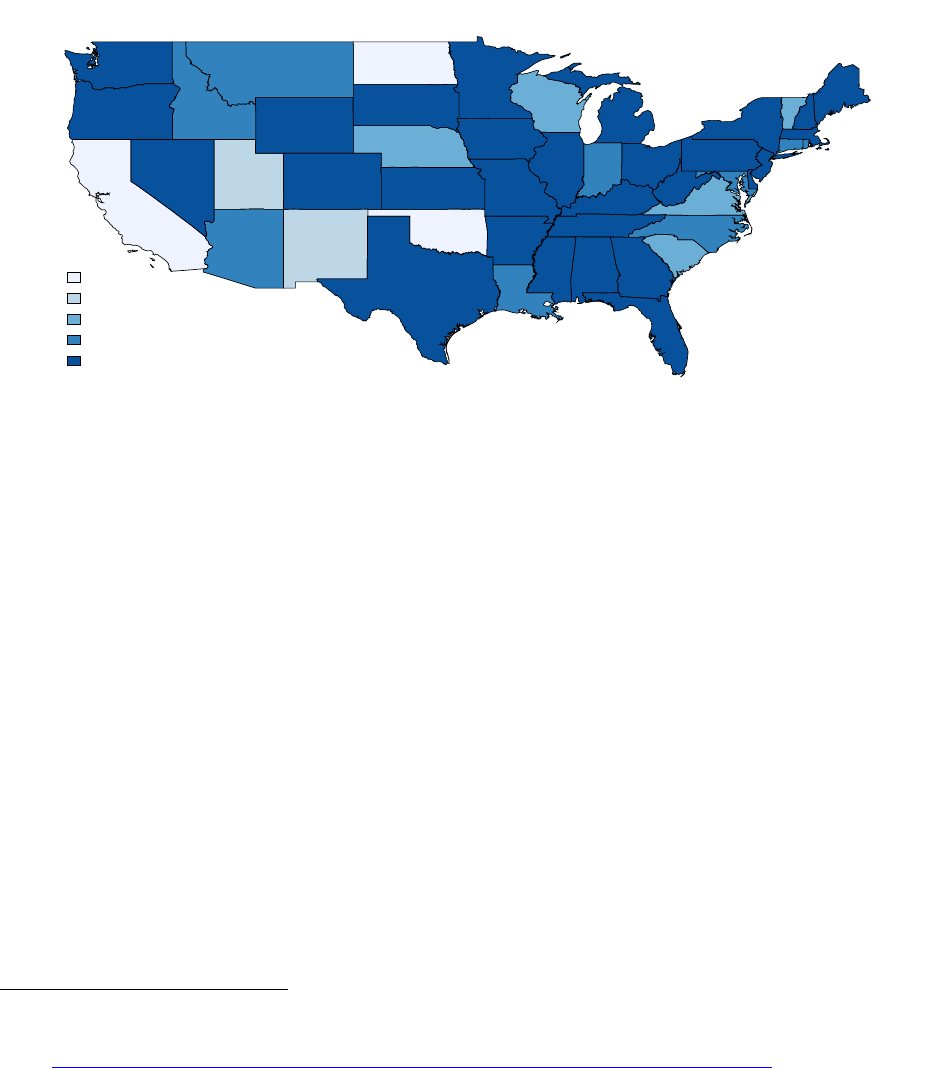

Currently, nearly all states will enforce non-compete agreements to some extent. Within those

states, non-compete enforcement may be restricted in a variety of ways that vary from state to

state. See Beck Reed Riden LLP for a summary of state rules.

20

Judicial modification of non-competes. Rather than declaring specific contracts completely

enforceable or unenforceable, courts in certain states may alter the contracts themselves. In

those states, judges may declare portions of a contract void but other parts to be valid under what

is called “blue pencil doctrine.”

The following stylized example may help to explain how this doctrine might work. Suppose that

a contract states that “The employee agrees not to work for any business competitive with the

employer for one year in the following counties: Leelanau, Benzie, and Manistee.” Purely

hypothetically, a judge might find the inclusion of Benzie to be overbroad, and could determine

that the non-compete is valid once Benzie County is removed. However, as blue-pencil doctrine

does not allow a court to add terms to a contract, the contract could not be revised to add “agrees

not to work in an administrative capacity”, were the court to hold that this qualifier was

necessary to prevent the contract from being overbroad.

In other states, an “equitable reform” or “reformation” doctrine allows judges to amend the

language in question to generate an enforceable contract consistent with the original intent of the

existing contract.

21

This allows more flexibility than the blue pencil rule and increases the

likelihood of a non-compete being upheld in some form, all else equal. It may also encourage

firms to take risks in the writing of contracts, including provisions likely to be struck down. If

workers do not have a good sense of which parts of a contract are enforceable, then these

untenable provisions may still affect their behavior. On the opposite end of the spectrum, some

states simply do not allow any judicial modification of contracts, but instead hold that any

unenforceable provisions render the entire contract unenforceable. This is sometimes known as

“red-pencil” doctrine.

20

Other summaries of non-compete law exist and are in some cases slightly inconsistent with the Beck Reed Riden

table we use; see “Summary of Covenants Not to Compete: A Global Perspective

” by Fenwick and West LLP, for

one alternative.

21

In some cases, this doctrine is (confusingly) also referred to as “blue-pencil.”

16

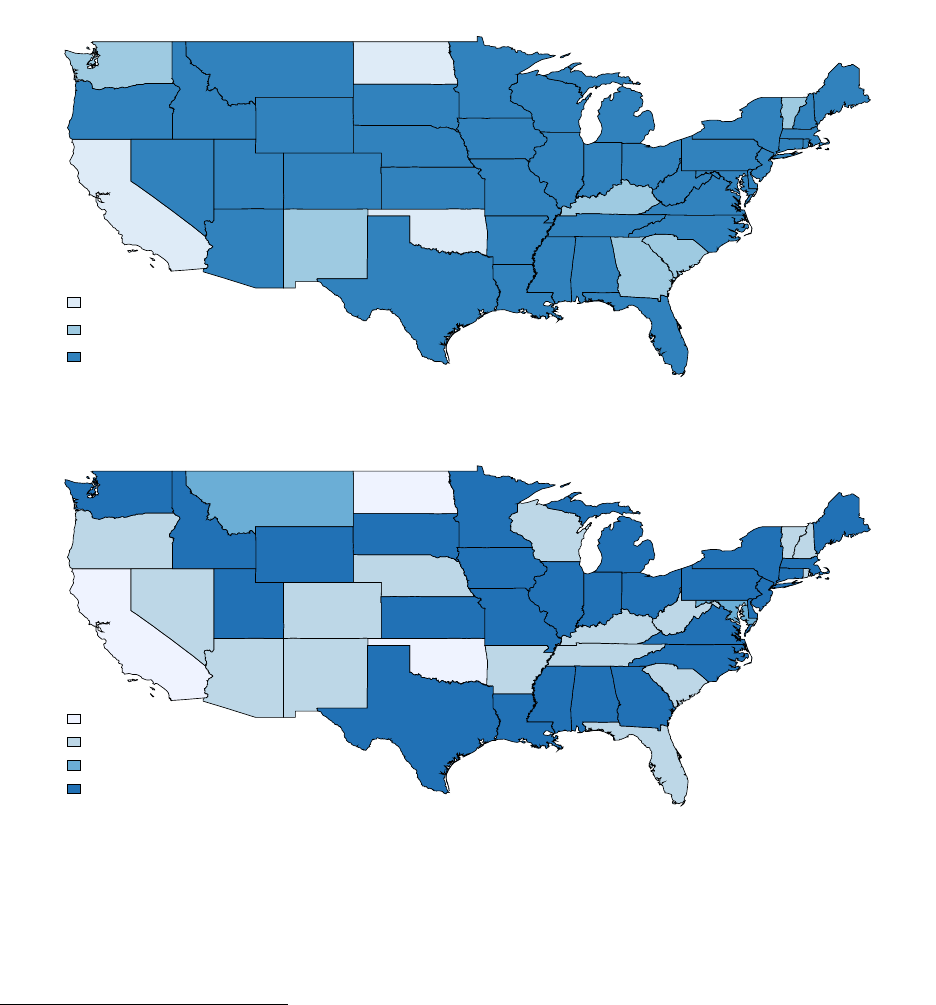

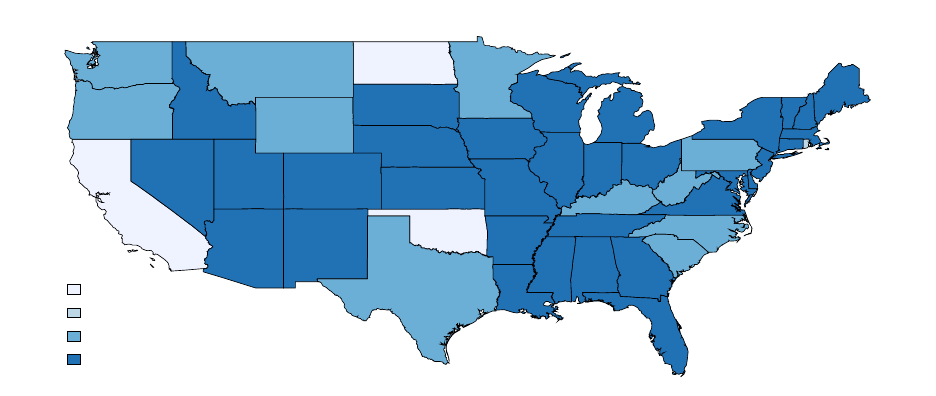

The figure below illustrates findings by one survey of the use of each rule by state.

22

See

Appendix B for additional figures illustrating the survey’s findings regarding other important

dimensions of non-compete enforcement, including treatment of trade secrets, enforceability in

case of firing without cause, and whether “continued employment” counts as worker

consideration in exchange for a non-compete.

Quits vs. Layoffs. The paradigmatic case of non-compete enforcement is one in which an

employee quits and is prevented from working for a competitor. However, even fired workers

are often bound by non-compete contracts. One survey reports that, as of 2015, non-competes

were enforceable against employees discharged without cause in about half of states.

23

Recent changes in non-compete enforcement. Several states have recently altered their

approaches to non-compete enforcement. Notably, Georgia amended its constitution in 2011 to

allow for increased enforcement of non-compete agreements.

24

Other states have altered their

statutes to extend or limit the reaches of non-competes, as with a recent statute in Alabama that

more explicitly explains what is and is not a valid protectable interest. Like Alabama, Oregon

passed a statute that more clearly defines the bounds of a non-compete. As of 2016, new non-

competes in Oregon will be limited to a maximum of 18-month duration. New Mexico also

22

Alaska and Hawaii, not shown, are both “reformation” states.

23

See Beck Reed Riden LLP (2015).

24

See http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=aadbea62-9a31-4ae3-92dd-8198906c37f6.

Not enforced

Undecided

Red pencil

Blue pencil

Reformation

Source: A State by State Survey of Employee Noncompetes, Beck Reed Riden

Non-compete Enforcement Regime

17

more clearly defined the bounds of non-competes, restricting their enforceability for certain

health care practitioners. In Hawaii, non-competes have been prohibited for tech workers.

25

In other states, legislators have recently proposed significant changes. A bill similar to that

passed in Hawaii was introduced, but not enacted, in Missouri. In New Jersey and Maryland,

bills were proposed that would render non-competes unenforceable for any workers eligible to

receive unemployment compensation. State legislators in Massachusetts, Michigan, and

Washington have proposed that non-competes be made largely unenforceable in their states.

Finally, Senators Franken and Murphy have proposed that firms be prohibited from entering into

non-compete agreements with workers making less than $15 per hour.

26

Appendix A provides a brief summary of the development of non-compete law over the long run.

25

See https://legiscan.com/AL/bill/HB352/2015, http://gov.oregonlive.com/bill/2015/HB3236/,

http://www.nmlegis.gov/lcs/legislation.aspx?chamber=S&legtype=B&legno=325&year=15, and

http://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/session2015/bills/HB1090_CD1_.HTM, for Alabama, Oregon, New Mexico, and

Hawaii law, respectively.

26

Private correspondence with Evan Starr. See

http://house.mo.gov/billtracking/bills151/billpdf/intro/HB0597I.PDF

,

http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2012/Bills/A4000/3970_I1.HTM,

http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2013RS/fnotes/bil_0001/sb0051.pdf, https://malegislature.gov/Bills/189/House/H1701,

http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(eemdorjddeyzki1vwou5lszu))/mileg.aspx?page=GetObject&objectName=2015-

HB-4198, http://app.leg.wa.gov/billinfo/summary.aspx?year=2015&bill=2931, for Missouri, New Jersey, Maryland,

Massachusetts, Michigan, and Washington, respectively. See

http://www.franken.senate.gov/files/documents/150604MOVEsummary.pdf for the proposed federal bill.

18

IV. Effects of Non-compete Enforcement

The effects of non-compete enforcement on mobility. According to authors of a recent study, the

state of Michigan inadvertently “legalized” non-competes in 1985.

27

This presented a rarely

available opportunity to study the effect of non-compete enforcement. Typically, it is difficult to

rule out the possibility that changes in law reflect changes in current or expected economic

circumstances. Thus, a simple comparison of economic outcomes before and after a state

legalizes non-competes will include the effects of both these changes in circumstances and non-

compete enforcement itself, making it difficult to separately estimate the latter effect. But in the

case of Michigan, with its allegedly accidental and unanticipated change in the enforceability of

non-competes, researchers can more reliably interpret changes in outcomes (e.g., labor mobility)

as being caused by non-compete enforcement.

Marx, Strumsky, and Fleming exploit this natural experiment, showing that worker job mobility

fell by 8 percent when non-competes were made enforceable, with the effect even larger for

workers with more narrowly-focused human capital. However, other authors dispute these

findings, arguing that the inadvertent legalization was not retroactive and that some states were

inappropriately labeled as “non-enforcing.”

28

In separate work, Marx finds that workers who do

switch jobs are more likely to leave their industry if they are covered by a non-compete, with the

attendant “reduced compensation, atrophy of their skills, and estrangement from their

professional networks” that would be expected to occur.

29

The effects of non-compete enforcement on wages. The literature on the effect of non-competes

on wages is small, consisting largely of case studies, surveys of specific professions (e.g.,

electrical engineers), theoretical papers, and a recent analysis based on a broad online survey.

30

We therefore combine information from previous literature on enforceability and non-compete

prevalence with standard labor market data, generating suggestive evidence on the wage impacts

27

See Marx and Fleming (2012) for details.

28

See Sichelman and Barnett (2015).

29

See Marx, Strumsky, and Fleming (2009) and Marx (2011).

30

See various papers by Marx, Marx and Fleming (2012), Meccheri (2009), and Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015),

respectively. We are not aware of any panel data with individual responses to questions about non-competes, and

existing work typically does not present population-wide inferences about the wage effects of non-compete

enforcement.

19

of non-compete enforcement.

31

Interestingly, we find stricter non-compete enforcement to be

associated with both lower wage growth and lower initial wages.

32

The first column of Table 1 shows the percentage change in wages from a one-unit increase in a

non-compete enforceability index, holding constant a number of worker characteristics.

33

It

suggests that a standard deviation in non-compete enforcement reduces wages by about 1.4

percent. Recent work by Starr and coauthors finds broadly similar results to those presented

here.

34

It is possible to refine this approach by focusing more narrowly on populations likely to be

affected by non-competes. Workers with bachelor's degrees are more than 50 percent more

likely to be bound by non-competes than those without, suggesting that one might better

approximate the “eligible” subgroup by restricting the sample to workers with bachelor's

degrees. This is shown in Table 1, column 2. Note that the magnitude of the wage effect of non-

compete enforcement increases for this subgroup, as expected. A slightly more nuanced

approach makes use of the occupational breakdown provided in recent work. Rather than

omitting non-college workers, we instead reweight the sample to be more representative of

workers with non-competes. For example, this will imply placing a higher weight on workers in

the architecture and engineering occupations than in the personal services occupations. Table 1,

column 3 shows results from this reweighted approach. The magnitude of the wage impact is

again above that of column 1, but not dramatically so.

35

31

We use the 2014 merged outgoing rotation groups of the Current Population Survey (CPS), which provide a cross

section of population-representative workers. Merged with this data is the Starr-Bishara index of non-compete

enforceability by state (generously provided by Evan Starr), as well as the fraction of workers with non-competes by

major occupation from Starr, Bishara, and Prescott (2015).

32

Here again, the particular proposed explanation for non-competes is important. For instance, if screening is the

dominant explanation, and workers are fully informed about non-competes, we would expect stricter enforcement to

cause an initial wage premium but slower subsequent wage growth. Workers would only be willing to sign the non-

compete if they were compensated at the time of signing. If, on the other hand, salience is the dominant

explanation, we would expect no initial premium and slower wage growth, as workers are prevented from taking

advantage of outside opportunities or using outside opportunities as leverage for wage growth at the current firm.

33

These controls consist of education, age, gender, marital status, occupation, industry, public sector status, and

union status.

34

See forthcoming work by Balasubramanian, Chang, Sakakibara, Sivadasan, and Starr, as well as Starr, Ganco, and

Campbell.

35

This is perhaps to be expected given the fact that that non-competes are used quite broadly. While non-competes

are more common in particular occupations (e.g., management, computer and mathematical, and architectural and

engineering occupations), they are also found in a wide variety of unexpected occupations and education levels.

20

Much of the research on non-competes has focused on their relationship with on-the-job training.

Non-competes and non-compete enforceability may affect the rate at which wages grow with

employee tenure and experience. We therefore examine the association of non-compete

enforceability with age-wage profiles, i.e., the rate at which wages increase with age.

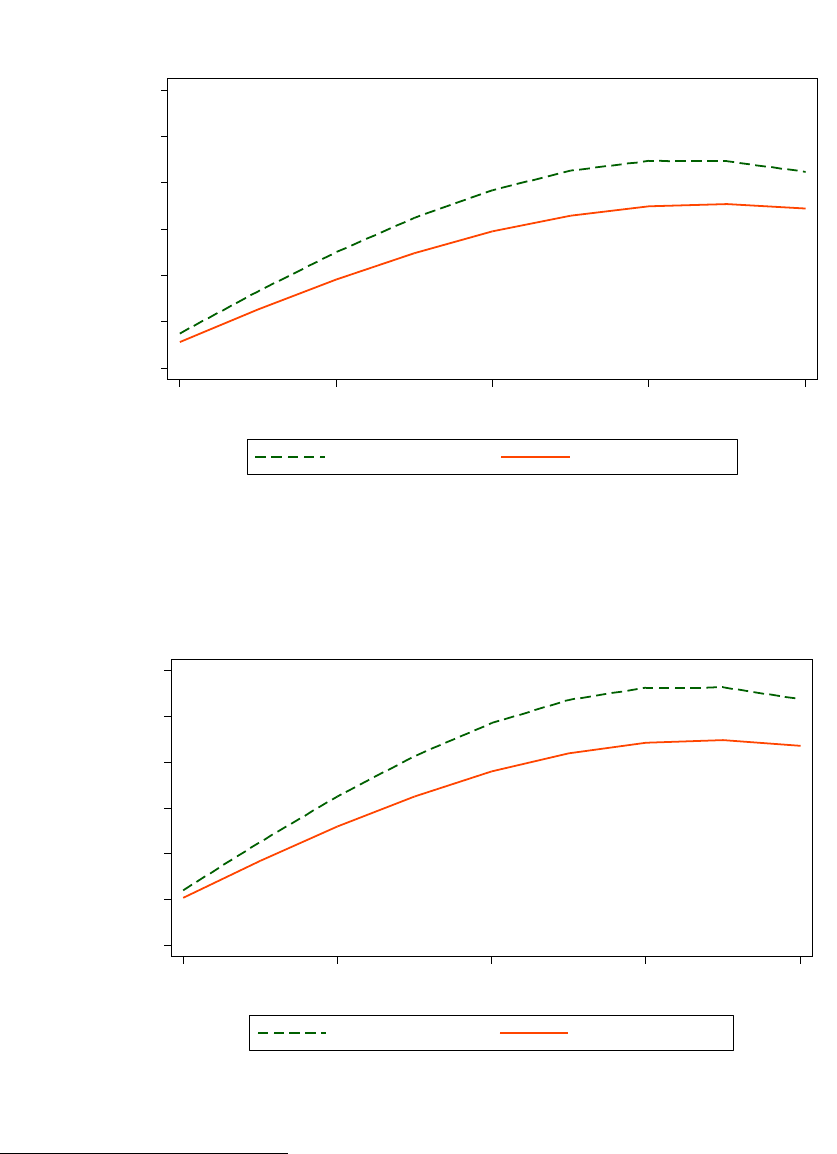

Figures 1 and 2 below are plots of age-wage profiles in a minimally-enforcing state and a

maximally-enforcing state, for original and occupation-reweighted samples, respectively. As

workers age, the effect of tightened non-compete enforcement appears to rise: using the original

sample, the effect of maximal enforcement, relative to minimal enforcement, is 5 percent at age

25 and 10 percent at age 50. As with the previous results, the occupation-reweighted projections

show a somewhat larger difference between wages in minimally- and maximally-enforcing

states.

Are these results surprising? If non-competes existed exclusively to promote training, one would

expect states with stronger enforcement to see faster wage growth over the life cycle. If, on the

other hand, non-competes are the product of a lack of salience for workers, one would instead

expect to see the pattern shown in Figures 1 and 2.

36

As workers progress through their careers,

switching jobs is more difficult in states that stringently enforce non-competes. Given that job

36

When interpreting any of the results just described, it should be remembered that we are not exploiting variation

over time in non-compete enforcement; rather, the wage estimates are derived from variation across states. Even

after controlling for available worker-level variables, states may differ in ways that are both relevant to wage growth

and non-compete enforcement. As such, the results shown here should be seen as merely suggestive.

Original sample College-only Occupation-reweighted

Enforcement -1.38% -1.86% -1.52%

(-13.55) (9.73) (12.49)

N 163,252 57,156 163,252

R

2

0.43 0.25 0.43

Source: 2014 Current Population Survey, Starr et al. (2015), private correspondence with Starr, and Treasury calculations. All

estimates are conditional on education, marital status, union status, sex, major occupation and industry, public sector status, and a

quadratic in age. T-statistics are in parentheses.

Table 1. Wage effect of one standard deviation of noncompete enforcement

21

switching is generally associated with substantial wage increases, this increased difficulty of

switching would reduce wage growth over time.

37

37

See Topel and Ward (1992).

12 14

16 18

20 22

24

Hourly wage

20

30

40

50

60

Age

No enforcement Max enforcement

Source: 2014 Current Population Survey, Starr et al. (2015), and Treasury calculations. All

variables, with the exception of enforcement index and age, are held constant at their means.

Original sample

Figure 1. Age-Wage Profile by State Enforcement Regime

12 14 16 18 20 22 24

Hourly wage

20 30 40 50 60

Age

No enforcement Max enforcement

Source: 2014 Current Population Survey, Starr et al. (2015), and Treasury calculations. All

variables, with the exception of enforcement index and age, are held constant at their means.

Occupation-reweighted

Figure 2. Age-Wage Profile by State Enforcement Regime

22

Non-compete enforcement and aggregate impacts. Thus far, we have discussed the effects of

non-competes on individual workers. But non-compete enforcement may matter for cities,

states, and regions in ways that cannot be fully understood at the individual level. Whether non-

competes are beneficial or harmful for a single worker and a single firm, there are potential

spillovers across workers and firms, particularly related to information.

In urban economics, regions are subject to so-called “agglomeration effects.” For instance, high-

tech firms do not locate randomly, but tend to cluster in places like Silicon Valley. This

clustering is due to a number of factors that include the availability of a large, deep pool of

workers with relevant skills, a more competitive market of suppliers, and information spillovers

across workers and firms. This last factor is important in connection with non-competes. When

firms in a given industry are clustered, it becomes easier for their workers to share expertise and

discoveries. While not always in the interest of a particular firm, this sharing can redound to the

advantage of the larger economy, making the cluster an attractive destination for firms.

One important facilitator of this sharing is, unsurprisingly, the movement of workers across firms

within industry. Employee departures impose costs on their firms, but yield benefits for

destination firms and act to broadly disseminate improvements in technologies and best

practices. Non-compete enforcement can stifle this mobility, thereby limiting the process that

leads to agglomeration economies.

Many observers have suggested that Silicon Valley is a prime example of this phenomenon.

38

California, along with some other states, generally does not enforce non-compete agreements. It

would be difficult to reach definitive conclusions about one instance of an industrial cluster, of

course. One fact contradicting the hypothesis of free mobility is that high-tech firms in Silicon

Valley have been alleged to collude to suppress wages and reduce “poaching.”

39

We do not

know precisely how this behavior interacts with use of non-competes; in other words, the

California firms may have been colluding as a substitute for using non-competes. Nevertheless,

the Silicon Valley example highlights the importance of information sharing facilitated by

worker mobility in some industrial clusters.

38

For example, see Gilson (1999).

39

See http://www.wsj.com/articles/judge-rejects-settlement-in-silicon-valley-wage-case-1407528633.

23

Singh and Marx look more broadly at informational spillovers and find that non-compete

enforcement reduces their scope. Furthermore, using the Michigan natural experiment and cross-

sectional data, Marx, Singh, and Fleming find that highly skilled workers tend to move from

enforcing to non-enforcing states. This suggests that non-competes play a role in “brain drain,”

potentially harming states that enforce non-competes more stringently.

40

Samila and Sorenson (2011) also examine the relationship between non-compete enforcement

and regional employment and entrepreneurship. They find that more stringent enforcement is

negatively related to both employment growth and entrepreneurship, consistent with results from

Marx and coauthors.

40

See Singh and Marx (2011) and Marx, Singh, and Fleming (2011). Note that this particular finding does not

speak to whether strict non-compete enforcement is harmful to the nation as a whole.

24

V. Directions for Reform

Until recently, the lack of comprehensive data and analysis of non-competes made it difficult to

evaluate the institution from a public policy perspective. However, recent research has

underlined some important stylized facts that help to inform ideal policy and distinguish between

various possible explanations for non-competes. First, non-competes are common in the labor

market across educational, occupational, and income groups. Many workers who do not report

possessing trade secrets are nonetheless covered by non-competes.

41

Second, workers are often

poorly informed about the existence and details of their non-competes, as well the relevant legal

implications. Some employers appear to be exploiting this lack of understanding in ways that

harm workers without producing corresponding benefits to society. Finally, while non-compete

enforcement is associated with increased training for some workers, the details of this

enforcement are important: strong “consideration” requirements can support training and wage

growth while diminishing the likelihood that non-compete contracts result purely from

inadequate worker knowledge.

The following are general reform recommendations related to the enforcement and use of non-

compete contracts. They are not intended to be detailed or exhaustive. Nonetheless, these are

promising avenues for state and/or federal policymakers to explore.

Increase transparency in the offering of non-competes.

Policymakers should act to inject transparency into the world of non-competes. To the extent

that firms are simply misleading their prospective workers, non-competes are straightforwardly

negative for employees. It is important to be precise about the forms that worker confusion can

take. Some workers may simply not realize that they have signed a non-compete or fail to

understand its ramifications. This sort of confusion could be addressed by a requirement that

employers make the contracts, as well as their implications for future mobility, more salient for

workers at the outset of an employment relationship. Relatedly, some workers who are aware of

their non-compete contract may nonetheless be confused about its legal enforceability.

41

It is worth noting, however, that this is based on worker self-reports; employers may disagree.

25

Encourage employers to use enforceable non-compete contracts.

Many firms write non-compete contracts that contain unenforceable, overbroad provisions.

Given the well-documented worker confusion about these contracts and the very low cost of

writing an unenforceable contract, employers can exert a chilling effect on worker behavior even

when their contracts are unenforceable. Conversely, states should explicitly specify the

constraints on enforceability of non-compete contracts, where possible.

Require that firms provide “consideration” to workers bound by non-compete contracts in

exchange for both signing and abiding by non-competes.

Some firms already provide severance payments to workers with non-competes.

42

For instance,

a worker who quits may receive 50 percent of her previous salary in exchange for abiding by the

terms of the non-compete. This limits the harm to workers while ensuring that firms retain the

ability to protect their interests with non-competes. Importantly, by requiring that firms incur a

cost when requesting a non-compete, this policy preserves the most socially valuable non-

compete agreements and discourages the least valuable, for which firms would not be willing to

pay.

Conclusion

Non-competes are a central labor market institution, with nearly one fifth of all American

workers currently bound by such a contract. Surprisingly, non-competes are widely distributed

across education, occupation, and income groups. Understanding the consequences of this

institution for workers and the broader economy is therefore of great importance, especially in

light of its central role in determining workers’ prospects for wage growth and job mobility.

42

See http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320187/000119312510161874/dex1023.htm.

26

Though non-compete contracts can have important social benefits, principally related to the

protection of trade secrets, a growing body of evidence suggests that they are frequently used in

ways that are inimical to the interests of workers and the broader economy. Enhancing the

transparency of non-competes, better aligning them with legitimate social purposes like

protection of trade secrets, and instituting minimal worker protections can all help to ensure that

non-compete contracts contribute to economic growth without unduly burdening workers.

Ryan Nunn in the Office of Economic Policy was the principal drafter of this report. Inquiries

should be directed to the Office of Economic Policy at (202) 622-2200.

27

Appendix A

Modern interpretations of non-compete agreements are often said to have their origin in

15

th

and 16

th

century English common law and are best understood in the context of that period’s

economic structure. The guild economy largely comprised three types of workers: the

apprentice, the journeyman, and the master craftsman. Custom required apprentices to train

under master craftsmen for an extended period until graduating to the status of journeyman.

Once a journeyman, the individual was free to work wherever he wished while he sought

entrance into the inner circle of master craftsmen. Non-compete agreements likely originated in

this context as journeymen replaced retiring master craftsmen by purchasing their businesses.

43

However, available case law suggests English courts tended to disfavor restraints on trade –

especially restraints initiated by an employer.

The most cited example from this period comes from The Dyer’s Case of 1414.

44

This

case is perhaps the first known example of a contractual restraint of trade. A London practitioner

prohibited his apprentice from pursuing his trade in the same city for six months following his

apprenticeship. The court ruled against the covenant.

45

According to some commentators, the

result produced two fundamental pillars of employment law.

46

The first was a policy in favor of

retaining skilled labor in the public domain. The second pillar promoted the right of all

individuals to seek a livelihood. These principles guided legal precedent for the next century.

Over time, some master craftsmen began to take on more apprentices than customary so

as to employ a larger staff at low cost.

47

The consequence of this strategy was an influx of

journeymen looking for ways to unseat master craftsmen. Some craftsmen addressed the

increased levels of competition by requiring apprentices and journeymen to sign non-compete

agreements.

48

The English Parliament brought attention to some of these practices in 1536 by

authoring the Act for Avoiding of Extracting Taken upon Apprentices.

49

The law attempted to

43

Harlan M. Blake, Employee Agreements Not to Compete, 73 Harvard Law Review 638 (1960).

44

The Dyer’s Case, Y.B. Mich. 2 Hen. 5, fol. 5, pl. 26 (1414).

45

Ibid.

46

Dan Messeloff, Giving the Green Light to Silicon Alley Employees: No-Compete Agreements between Internet

Companies and Employees under New York Law, Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law

Journal, (vol. 11, issue 3, 2001), at 710-711. Much of this appendix benefits from this article.

47

Blake, supra note 39, at 633.

48

Ibid.

49

Bland, Brown & Tawney, English Economic History – Select Documents, (1919), at 284-286.

28

restrain some of the practices of guild masters – including non-compete contracts. In 1563, the

Statute of Artificers restricted the privileges of workers while also shifting power from guild

masters to the evolving English state.

50

The law established national constraints on maximum

wages and the length of apprenticeships.

51

By the beginning of the 17

th

century, courts continued to disfavor employment restraints,

whether in the form of time or place. An excerpt from Colgate v. Bacheler (1602) notes, “For as

well as [employers] may restrain [employees] for one time, or one place, [they] may restrain

[them] for longer times, and more places, which is against the benefit of the Common-wealth….

For he ought not be abridged of his Trade, and Living.”

52

Others worried that non-compete

covenants forced young men into “idleness”.

53

However, as a new economic system emerged,

English courts began to rethink their position on non-compete covenants.

Mitchel v. Reynolds (1711) marked a distinct shift away from the practice of completely

banning non-competes.

54

Reynolds, a baker, agreed to rent his bakery for five years. In return,

Mitchel pledged Reynolds a bond worth 50 pounds on the condition that Reynolds would not

resume his trade within St. Andrew Holborn Parish for 5 years. The latter failed to keep the

agreement and Mitchel sued. Chief Justice Parker ruled in favor of the agreement.

55

He

reasoned that while general restraints on trade were unlawful, as they benefited neither party,

some partial restraints were reasonable.

56

Effectively, the ruling permitted individuals to enter

agreements even if they restricted one’s ability to work in a particular location or for a certain

period, as long as both parties and the affected communities benefited from the arrangement.

However, employers were required to demonstrate the economic necessity of any such

agreement.

50

Donald Woodward, The Background to the Statute of Artificers: The Genesis of Labour Policy, 1558-63, The

Economic History Review (vol. 33, no.1) 1980, at 32-44.

51

Ibid.

52

Cro. Eliz. 872, 78 English Report 1097, (Queen’s Bench 1602).

53

Case of Tailors of Ipswich, 77 English Report 1218, 1219 (King’s Bench 1614).

54

Mitchel v. Reynolds, 24 English Report 347 (Queen’s Bench 1711).

55

Dan Messeloff, Giving the Green Light to Silicon Alley Employees: No-Compete Agreements between Internet

Companies and Employees under New York Law, Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law

Journal, (vol. 11, issue 3, 2001), at 710-711.

56

“General” restraints were defined as those with unlimited scope in either time or space, while “partial” restrains

were those limited in both dimensions.

29

The economic significance of non-competes evolved as new technology accompanied the

Industrial Revolution.

57

Once limited to local markets, companies began expanding into national

and international markets, exposing themselves to new rivals.

58

Moreover, corporations were

increasingly concerned with worker mobility. Leaving one’s town no longer carried the same

economic and physical risks. Homer v. Ashford (1825) describes the logic applied by English

courts on matters of non-compete covenants:

A merchant or manufacture would soon find a rival in every one of his

servants if he could not prevent them from using to his prejudice the

knowledge they acquired in his employ. Engagements of this sort between

masters and servants are not injurious restraints of trade, but securities

necessary for those who engage in it. The effect of such contracts is to

encourage rather than cramp the employment of capital in trade and the

promotion of industry.

59

Some took the argument of the court to suggest that non-compete clauses were

permissible in most circumstances. Six years later, the court clarified that while employers

should have access to protection, Mitchel’s test-of-reason still applied. In Horner v. Graves

(1831), a dentist’s assistant contracted to not practice independently within 100 miles of the

original employer.

60

Soon after parting with his employer, the assistant broke the agreement,

prompting the dentist to sue. In response, the court sided with the defendant, explaining that a

reasonable restraint must also account for the interests of the public. From the public’s

perspective, the dentist had sought to withhold a valuable service within the 100 mile radius of

his practice in order to protect himself. The court determined that the burden placed on the

public was greater than the need to protect the interests of the previous employer and that the

requirement was unreasonably broad.

61

The intermittent reweighting of employer, worker, and public interests continued as the

19

th

century wore on. By 1841, although most English courts still rejected general restraints,

some began to enforce them as businesses globalized.

62

A trend toward pro-employer policy

57

See Messeloff, supra note 42, at 712-713.

58

Blake, supra note 39, at 638.

59

Homer v. Ashford, 3 Bing. 322, 327 (1825).

60

7 Bing. 735, 131 English Report 284 (C.P. 1831).

61

Ibid. at 743.

62

Blake, supra note 39, at 624.

30

continued in 1853 when the Queen’s Bench ruled that the burden of showing unreasonableness

rested on the employee rather than employer.

63

In 1875, the court ruled that while contracts must

remain reasonable, a central value of the liberal economic philosophy permitted men of sound

mind to enter arrangements as they saw fit.

64

Increasing emphasis on freedom of contract was

evident in Rousillon v. Rousillon (1880), where the court allowed covenantal protection to extend

beyond national borders. The court reasoned that if the contract was reasonable in scope at the

negotiation, changing economic circumstances should not bar enforcement.

65,66

As English courts were moving toward pro-employer policies, American courts started

developing their own body of common law. In 1851, Lawrence v. Kidder, a case before the New

York Supreme Court, established a precedent that the state’s priority was to deter

monopolies.

67,68

The court reasoned that as far as possible, the state must ensure that all citizens

be permitted to work.

69

As such, the court viewed agreements which barred individuals from

practicing their occupations based on state or territory boundaries as unlawful.

A Pennsylvania court made an important distinction in 1866 between the sale of

“handicraft” and the sale of “property”.

70

The Pennsylvania court deemed restrictions on

property much more reasonable than restrictions on the use of an employee’s skills. This

distinction laid the foundation for the landmark Supreme Court decision in Oregon Steam

Navigation Co. v. Winsor (1874).

71

The California Steam Navigation Company sold the Oregon

Steam Navigation Company a boat under the condition that they would not operate the vessel

within California for a period of ten years. The Oregon Steam Navigation Company

subsequently sold it to Winsor, who at the time of sale was engaged in the navigation of water in

Washington. The sale was subject to a condition (among others) that Winsor would not operate

the boat in California for a period of ten years. The court upheld the condition, noting that there

was no injury to the public.

72

63

Tallis v. Tallis, I El. & B. 391, 118 English Report 482 (Queen’s Bench 1853).

64

Printing & Numerical Registering Co. v. Sampson, L.R. 19 Eq. 462 (1875).

65

14 Ch. D. 351 (1880).

66

Blake, supra note 39, at 641.

67

10 Barb. 641 (N.Y. Supreme Court 1851)

68

Blake, supra note 39, at 644.

69

Ibid.

70

Keeler v. Taylor, 53 Pa. 467, 470 (1866).

71

Messeloff, supra note 42, at 720-721.

72

Ibid.

31

The New York Court of Appeals echoed the opinion of the Supreme Court in 1887 when

it ruled in favor of a non-compete clause which restricted selling matches in the states of Nevada

and Montana.

73

The court found that the condition was a “partial” restraint even though it

covered the entire state of New York, while noting that the distinction between “general” and

“partial” restraints, while still good law, was weakening.

74

Non-compete policies began diverging across states by the end of the 19

th

century.

Notably, the California legislature rendered non-competes generally unenforceable.

75

Outside of

legal opinions, the most influential American documents on contract law are the “Restatement of

Contracts” of 1932 and its revision in 1979.

76

Though non-binding, these writings, published by

the American Law Institute, codify case law. Both versions of the Restatement of Contracts state

that restraints are unlawful if they unjustly benefit employers and impose undue hardship on the

employee or public – reflecting the opinion in Horner v. Graves.

77

The second Restatement of

Contracts protects the employee further by increasing the standard by which an employer must

demonstrate legitimate need for non-compete protection.

78

73

Diamond Match v. Roeber 106 N.Y. 473 (1887).

74

Messeloff, supra note 42, at 722.

75

Messeloff, supra note 42, at 714.

76

Ibid. at 723-724.

77

Ibid.

78

Ibid.

32

Appendix B

The following figures show some of the state heterogeneity in non-compete enforcement as of

2015. Note, however, that they reflect one particular expert’s view of state law, and may elide

distinctions relevant to some specific cases.

79

79

Hawaii considers trade secrets to be a protectable interest, is undecided on the question of enforcement against

workers fired without cause, and regards continued employment as sufficient consideration. Alaska is identical,

with the exception that it is undecided as to whether continued employment constitutes sufficient consideration.

Not applicable

Not protectable

Protectable

Source: A State by State Survey of Employee Noncompetes, Beck Reed Riden

Trade Secrets as Legitimate Interests

Not applicable

Undecided

Not enforceable

Enforceable

Source: A State by State Survey of Employee Non-competes, Beck Reed Riden

Enforceable Against Workers Fired Without Cause

33

Not applicable

Undecided

Not sufficient consideration

Sufficient consideration

Source: A State by State Survey of Employee Noncompetes, Beck Reed Riden

Continued Employment as Sufficient Consideration

34

Works Cited

Balasubramanian, Natarajan, Jin Woo Chang, Mariko Sakakibara, Jadadeesh Sivadasan, and

Evan Starr. 2016. “Locked In? Noncompete Enforceability and the Mobility and Earnings of

High Tech Workers.” Working paper.

Beck Reed Riden LLP. 2015. “Employee Noncompetes: A State by State Survey.”

http://www.beckreedriden.com/50-state-noncompete-survey/.

Becker, Gary S. 1962. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Political

Economy 70 (5): 9–49.

Blake, Harlan M. 1960. “Employee Agreements Not to Compete.” Harvard Law Review 73:

625–691.

Bland, Brown, and Tawney. 1915. “English Economic History–Select Documents.” The

American Historical Review 20 (3): 621–623.

Case of Tailors of Ipswich, (1614) 77 K.B. 1218, 1219 (E.R.).

Cro. Eliz. 872, (1602) 78 Q.B. 1097, (E.R.).

Diamond Match v. Roeber (1887) 106 N.Y. 473 (N.Y. Court of Appeals).

Feldman, Katuscak, and Kawano. 2016. “Taxpayer Confusion: Evidence from the Child Tax

Credit.” Forthcoming in the American Economic Review.

Forbes. “Does Jimmy Johns Non-Compete Clause for Sandwich Makers have Legal Legs?”

http://www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2014/10/15/does-jimmy-johns-non-compete-clause-

for-sandwich-makers-have-legal-legs/.

Gilson, Ronald J. 1999. “The Legal Infrastructure of High Technology Industrial Districts:

Silicon Valley, Route 128, and Covenants Not to Compete.” New York University Law Review

74 (3): 575–629.

Hamermesh, D. S. 1995. “Labour Demand and the Source of Adjustment Costs.” Economic

Journal 105 (430): 620–634.

Homer v. Ashford, (1825) 3 Bing. 322, 327 (E.R.).

Horner v. Graves (1831) 7 Bing. 735, 131 C.P. 284 (E.R.).

Kahneman, Daniel. 2003. “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral

Economics.” The American Economic Review 93 (5): 1449–1475.

35

Keeler v. Taylor, (1866) 53 Pa. 467, 470 (Penn. Supreme Court).

Lawrence v. Kidder (1851) 10 Barb. 641 (N.Y. Supreme Court).

Malsburger, Brian. 1998. “Covenants Not to Compete: A State by State Survey.” Arlington: The

Bureau of National Affairs.

Marx, Matt, and Lee Fleming. 2012. “Non-compete Agreements: Barriers to Entry…and Exit?”

In Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 12, 39-64. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Marx, Matt, Deborah Strumsky and Lee Flemming. 2009. “Mobility, Skills, and the Michigan

Non-Compete Experiment.” Management Science 55 (6): 875–889.

Marx, Matt, Jasjit Singh and Lee Flemming. 2011. “Regional Disadvantage? Non-Compete

Agreements and Brain Drain.” Research Policy 44 (2): 394–404.

Marx, Matt. 2011. “The Firm Strikes Back: Non-compete Agreements and the Mobility of the

Technical Professionals.” American Sociological Review 76 (5): 695–712.

Mason v. Provident Clothing & Supply Co. (1913) A.C. 724 (H.R.) (Eng.) and Herbert Morris,

Ltd. v. Saxelby, (1916) I A.C. 688 (H.L.) (Eng.).

Messeloff, Daniel. 2001. “Giving the Green Light to Silicon Alley Employees: No-Compete

Agreements between Internet Companies and Employees under New York Law.” Fordham

Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal 11 (3): 710–746.

Mitchel v. Reynolds, (1711) 24 Q.B. 347 (E.R.).

Nordenfelt v. Maxim Nordenfelt Guns & Ammunition Co., (1984) A.C. 535, 536 (H.L.) (Eng.).

Oregon Steam Navigation Co. v. Winsor 87 S. Ct. (20 Wall.) 64 (1873).

Printing & Numerical Registering Co. v. Sampson, (1875) 19 Eq. 462 (L.R.).

Rousillon v. Rousillon (1880) 14 Ch. D. 351.

Salop, Joanne and Steven Salop. 1976. “Self-Selection and Turnover in the Labor Market.” The

Quarterly Journal of Economics 90 (4): 619-27.

Samila, Sampsa and Olav Sorenson. 2011. “Noncompete Covenants: Incentives to Innovate or

Impediments to Growth.” Management Science 57: 425:38.

36

Sichelman, Ted and Jonathan Barnett. 2015. “Revisiting Labor Mobility in Innovation Markets.”

Working paper.

Starr, Evan, Martin Ganco and Ben Campbell. 2016. “Redirect and Retain: Why and How Firms

Capitalize on Noncompete Enforceability in Technical and Business Occupations.” Working

paper.

Starr, Evan, Norman Bishara and JJ Present. 2015. “Noncompetes in the U.S. Labor Force.”

Working paper.

Starr, Evan. 2015. “Consider This: Firm-Sponsored Training and the Enforceability of Covenants

Not to Compete.” Working paper.

Tallis v. Tallis, I El. & B. 391, (1853) 118 Q.B. 482 (E.R.).

The Dyer’s Case, (1414) Y.B. Mich. 2 Hen. 5, fol. 5, pl. 26.

Thompson Hine LLP. “Georgia’s Restrictive Covenants Act: Putting the “Non” in Noncompete.”

Lexology, http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=aadbea62-9a31-4ae3-92dd-

8198906c37f6.

Topel, Robert H. and Michael P. Ward. 1992. “Job Mobility and the Careers of Young Men.”

The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (2): 439–179.

Wall Street Journal. “Judge Rejects Settlement in Silicon Valley Wage Case.”

http://www.wsj.com/articles/judge-rejects-settlement-in-silicon-valley-wage-case-1407528633.

Woodward, Donald. 1980. “The Background to the Statute of Artificers: The Genesis of Labour

Policy, 1558-63.” The Economic History Review 33 (1): 32–44.