DEPICTING the

CR EATION of a NATION

The Story Behind the Murals

About Our Founding Documents

by LESTER S. GORELIC

T

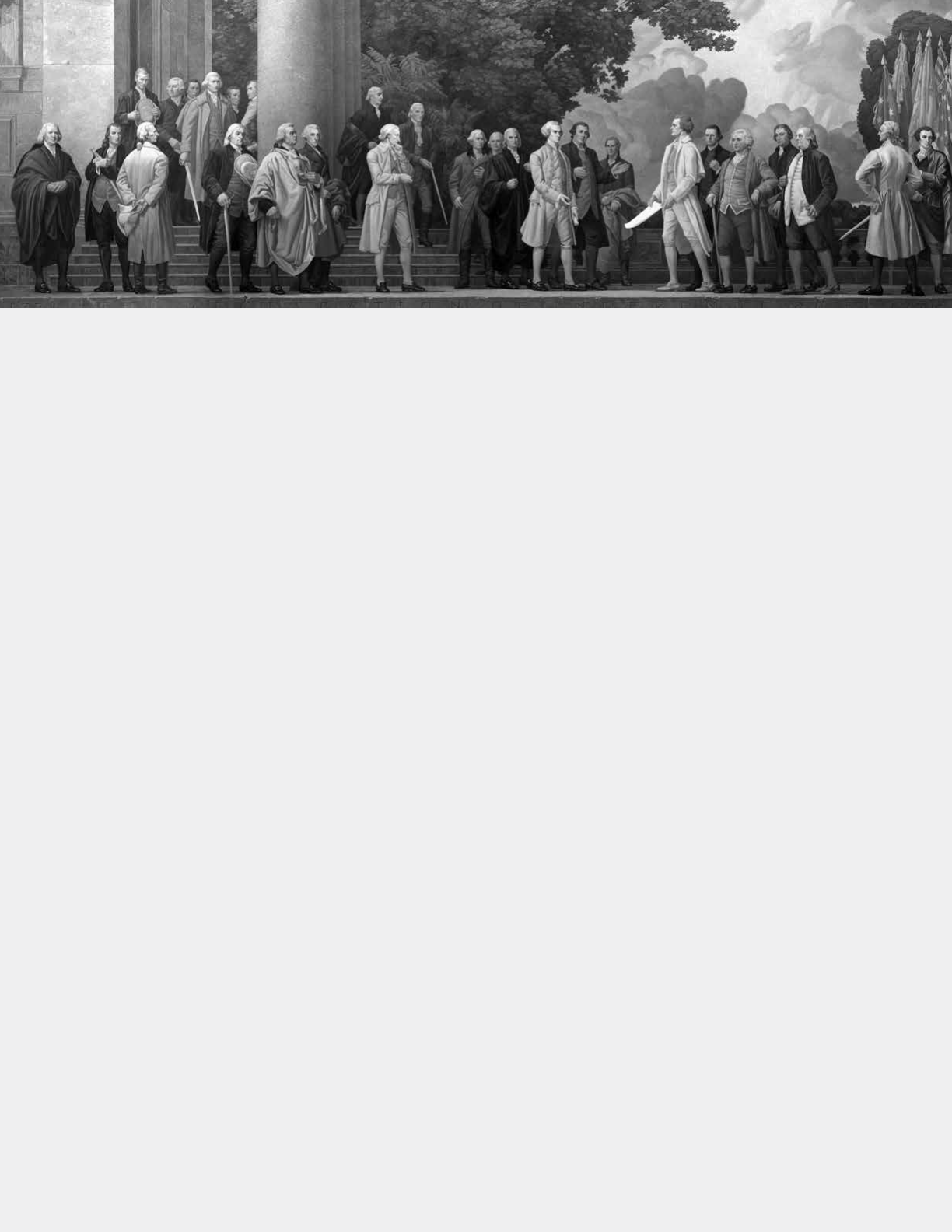

wo large oil-on-canvas murals (each about 14 feet by 37.5

feet) decorate the walls of the Rotunda of the National

Archives in Washington, D.C. e murals depict pivotal

moments in American history represented by two founding doc-

uments: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

In one mural, omas Jefferson of Virginia is depicted handing over his careful-

ly worded and carefully edited draft of the Declaration of Independence to John

Hancock of Massachusetts. Many of the other Founding Fathers look on, some fully

supportive, some apprehensive.

In the other, James Madison of Virginia is depicted presenting his draft of the

Constitution to fellow Virginian George Washington, president of the 1787

Constitutional Convention, and to other members of the Convention.

Although these moments occurred in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia

(Independence Hall)—not in the sylvan settings shown in the murals—the two price-

less documents are now in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and

have been seen by millions of visitors over the years.

When the National Archives Building was built in the

mid-1930s, however, these two founding documents were

in the custody of the Library of Congress and would not

be transferred to the Archives until 1952. Even so, the ar-

chitects designed and built an exhibition hall that included

space for two large murals celebrating the documents.

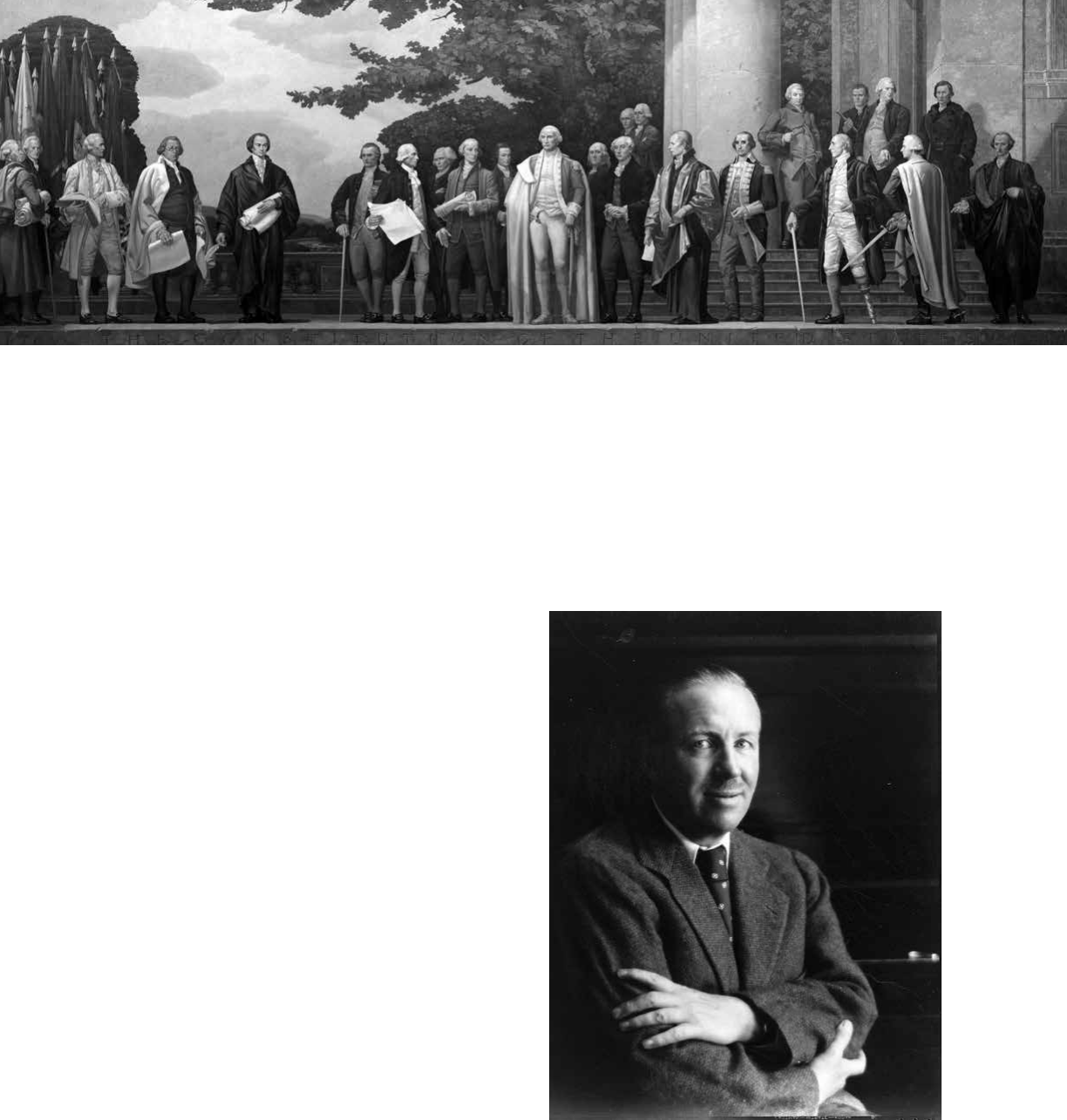

Creating the murals would prove not to be a simple

task. e muralist commissioned for the project, Barry

Faulkner, had to serve a number of masters, including the

architects, the historical community, and the United States

Commission of Fine Arts. Faulkner submitted numerous

preliminary sketches to the commission, only to be reject-

ed. At one point, it appeared that the entire mural project

was in jeopardy.

e details of how the paintings were conceived and

their meanings tell a fascinating back story of American

public art, allegory, and American history.

DELEGATES’ PLACEMENTS IN DECLARATION

BASED ON VIEWS ON INDEPENDENCE

In depicting Jefferson presenting the draft of the

Declaration to the Congress, Faulkner portrays the

Committee of Five, who were charged with compos-

ing a declaration (omas Jefferson, John Adams of

Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Roger

Sherman of Connecticut, and Robert Livingston of New

York). Included with these five are John Hancock and

Virginians Benjamin Harrison and Richard Henry Lee,

who made the motion for independence. All of these men

stand in the front rows of the right side of the mural.

Lee, who did not see military action during the

Revolution, stands defiantly with sword in hand—likely

symbolic for his emotion-filled “call-to arms” speech as he

made his motion to officially declare independence.

Jefferson’s placement at the front of the Committee of

Five reflects his position as its head. Although Jefferson was

the primary author of the Declaration, his initial draft was

edited first by Adams and then by Franklin. e noticeable

difference in clothing styles of Adams and Jefferson (as well

as Lee) reflects a suggestion made to Faulkner to use cloth-

ing to distinguish “the Puritan and Cavalier strains” (New

England and Southerners) at the Congress.

Barry Faulkner, a noted American muralist, submitted several sketches

or studies before the large murals of the National Archives Exhibit

Hall took nal form. Top: The Declaration of Independence (left) and the

Constitution of the United States (right) have decorated the walls of the

National Archives Rotunda since their installation in 1936.

Depicting the Creation of a Nation

Prologue

45

Spring 2014

To the left of Jefferson, Hancock, president

of the Congress, is partnered with Benjamin

Harrison, who served as the chairman of the

Committee of the Whole. Hancock is por-

trayed as poised to receive the draft from

Jefferson. Harrison is shown with arms wide

open, welcoming the Congress into his com-

mittee to discuss the draft.

On the left side of the mural are two

groupings. e first consists of John

Dickinson of Pennsylvania (hand on

chin), standing to the right and somewhat

apart from the group composed of Samuel

Adams of Massachusetts, Stephen Hopkins

of Rhode Island, and omas McKean of

Delaware. ese four men were leaders of

the revolutionary movement in the colonies

but approached the issues differently.

Dickinson, a conservative revolutionary,

preferred negotiation over revolution. He

would ultimately abstain from voting on

independence. e remaining men, with a

cloaked Sam Adams in an oratorical stance

and with an expression matching his “fire-

brand” reputation, advocated the overthrow

of British rule.

CLOTHING, OTHER PROPS

REVEAL LIVES OF DELEGATES

e three men at the extreme left—

Charles Carroll and Samuel Chase, both

of Maryland, and Robert Morris of

Pennsylvania—worked for independence

behind the scenes through the “secret com-

mittees” of the Congress.

Carroll and Chase had been commissioned

by the Committee of Correspondence to

negotiate an alliance with Canada to join in

the fight against the British as the 14th state.

Morris, a member of the Committee of Secret

Correspondence and the Secret Committee

of Trade, as was Carroll, coordinated the ac-

quisition of munitions and shipment of arms.

Morris was also involved in gathering intel-

ligence on British troop movements through

his worldwide shipping fleet. Morris has been

called the “Financier of the Revolution” and

would later become the superintendent of

46 Prologue

finance for the first central bank of the new

republic, the Bank of North America.

e committee that drafted the Articles of

Confederation is represented by Dickinson

(chairman), John Adams, Josiah Bartlett of

New Hampshire, William Ellery of Rhode

Island, Hancock, Samuel Huntington of

Connecticut, Lee, Robert Morris, omas

McKean of Delaware, Roger Sherman, and

John Witherspoon of New Jersey.

Faulkner uses costuming and props to

provide a glimpse of the professional and

personal lives of some of the delegates.

Hancock, dressed in elegant cloth-

ing, came from the elite of Boston society.

e small roll of paper in his right hand

likely represents the speech he gave after

the Boston Massacre, dispelling any of the

prior doubts of Bostonians about his pa-

triotism. McKean was a judge and is por-

trayed with a Pennsylvania court judicial

gown draped over his arm. Wythe, wearing

a black robe, was America’s first law profes-

sor. Witherspoon, also in black robes, was

the president of the College of New Jersey.

John Adams, Hopkins, and William Floyd

of New York are portrayed with walking

sticks, a symbol of authority and wealth.

Hopkins, considered an early true patriot,

and Joseph Hewes of North Carolina are

portrayed with hats and clothing reflect-

ing their Quaker backgrounds. (Ironically,

Hewes would later become the first secretary

of naval affairs.) Bartlett is brandishing a

sword symbolic of his having been a com-

mander in the New Hampshire militia.

FOR THE CONSTITUTION:

COMMITTEES AND PLANS

Faulkner painted a clear sky and a “tro-

phy” of state flags of each of the 13 original

colonies to convey that the Constitution was

written during a time of peace and that the

individual states were joined in a union un-

der the Constitution.

In the Constitution mural, which faces

the Declaration of Independence mural,

Faulkner portrays the chairmen of two

committees—John Rutledge of South

Carolina, and William Samuel Johnson of

Connecticut—in the front row. e chair-

man of his third committee, Elbridge Gerry

of Massachusetts, is portrayed centrally but

diminutively in a back row.

Edmund Randolph of Virginia, portrayed

obscurely and paired with and behind

Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts at the

extreme left, presented to the Convention

a draft plan—the Virginia Plan, which

served as the working document for the

Constitution. Gorham was the chairman of

the Committee of the Whole, which deliber-

ated for first two months of the Convention

on Randolph’s plan. e bundle of parch-

ment Gorham carries likely represents the

record of these deliberations, a record that

became the Gorham Report.

To the right of Gorham is Rutledge (holding

a book), whose “Committee of Detail” incor-

porated all the details of the Gorham Report

into the first draft of the Constitution. e oth-

er members of this committee were Randolph,

Gorham, James Wilson of Pennsylvania (to

the right of Rutledge), and Oliver Ellsworth

of Connecticut (right of Wilson).

Two drafts of a Constitution were actu-

ally generated by Rutledge’s committee.

Wilson contributed several key elements to a

somewhat disjointed preliminary first draft,

among which were the Electoral College and

the guiding principle of separation of powers.

He also proposed the slavery compromise and

would go on to almost singlehandedly hand-

write the second draft, which would serve

with little correction as the working docu-

ment for Johnson’s committee.

Ellsworth, through his additional partici-

pation in Gerry’s committee, had been the

primary advocate for and one of two archi-

tects (with Roger Sherman) of the Great

Compromise, which resolved how states

would be represented in the legislature.

Ellsworth is portrayed holding a partially

unrolled and disorganized document, likely

symbolizing the preliminary draft, and a

quill symbolizing his role in the compromise.

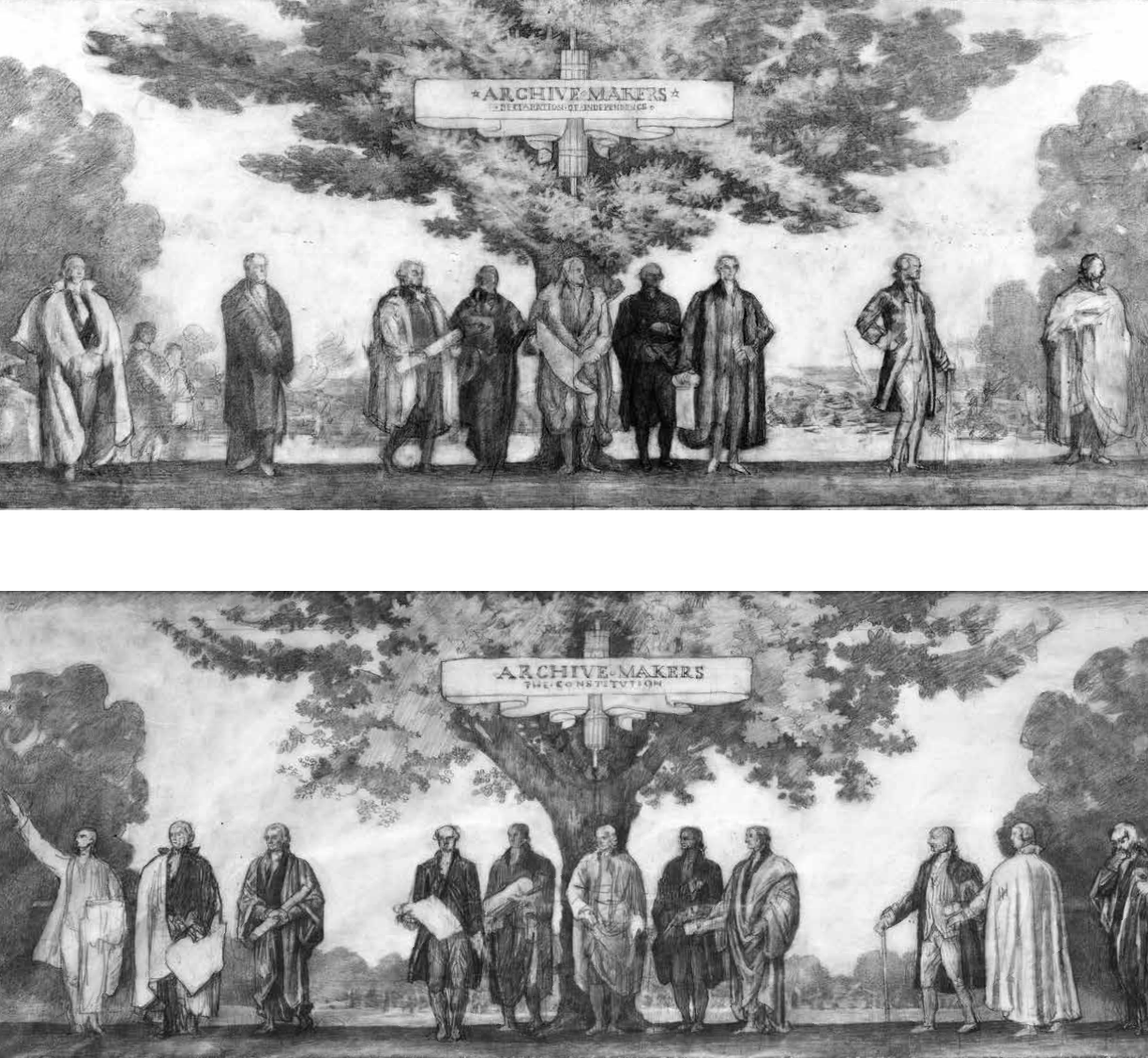

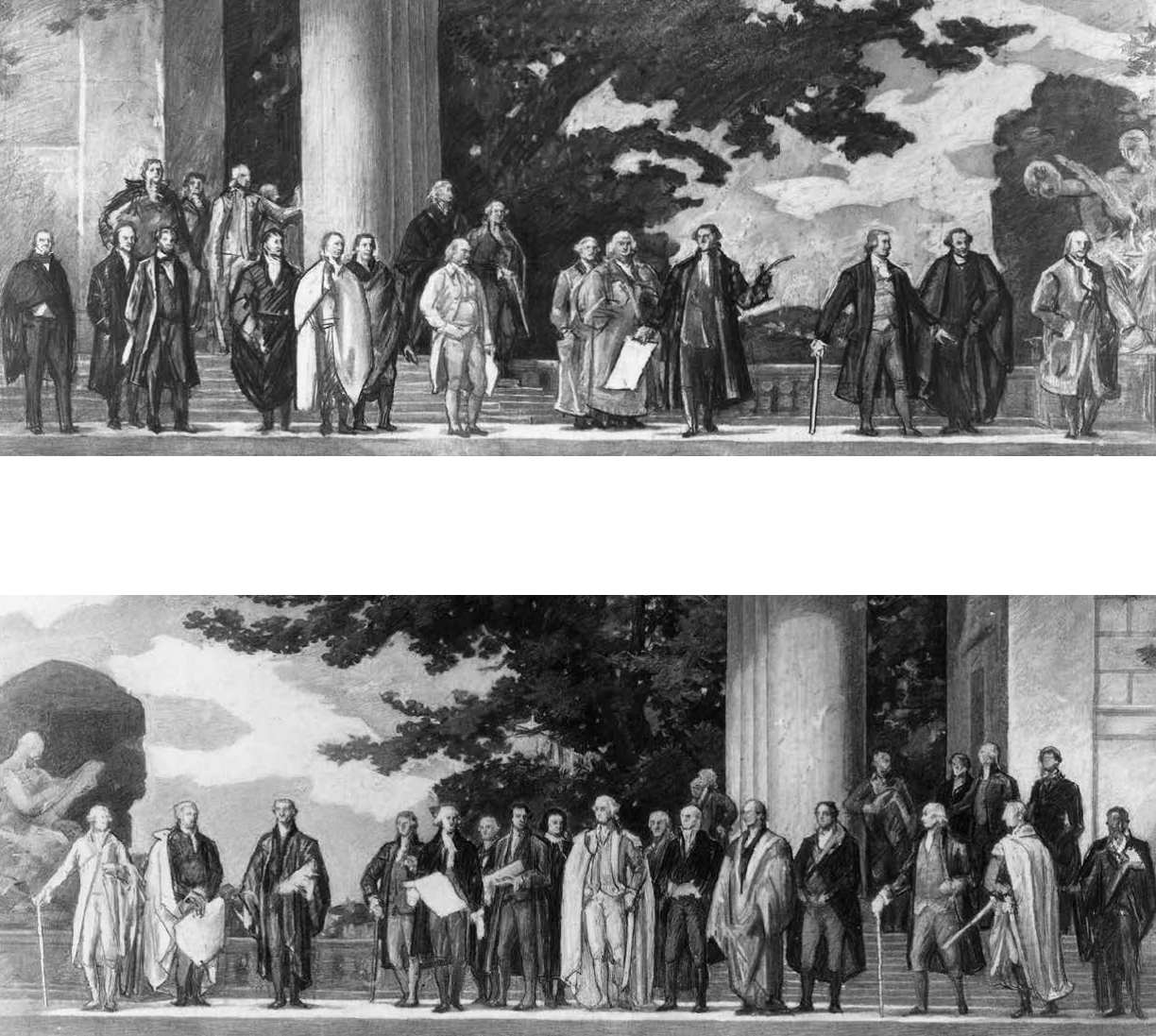

The Archive Makers sketches supported the bid for the contract. Above: The Declaration featured, left to right, unknown, R. Morris, unknown, unknown, B. Franklin, un-

known,T. Jefferson, S.Adams, R. H. Lee. Bottom: The Constitution featured, left to right,A. Hamilton, J. Monroe, O. Ellsworth, J. Madison, J. Dickinson, G. Mason, E. Randolph,

J. Jay, Gouverneur Morris, G.Washington, J. Marshall.

Johnson’s committee, the Committee of

Style and Arrangement, accepted the draft

from Rutledge’s committee and used it to

produce the final draft of the Constitution,

represented by the carefully rolled docu-

ment cradled in his hands. e members of

Depicting the Creation of a Nation

this committee were Alexander Hamilton of

New York, G. Morris, Madison, and Rufus

King of Massachusetts.

Madison, to the left of Johnson, is shown

symbolically submitting “the original draft of

the Constitution to Washington and a group

of the Convention members.” Behind and

paired with him is Charles Pinckney of South

Carolina, who had presented a plan to the

Convention at the same time as Randolph,

the elements of which were integrated into

the final draft without prior discussion.

Prologue 47

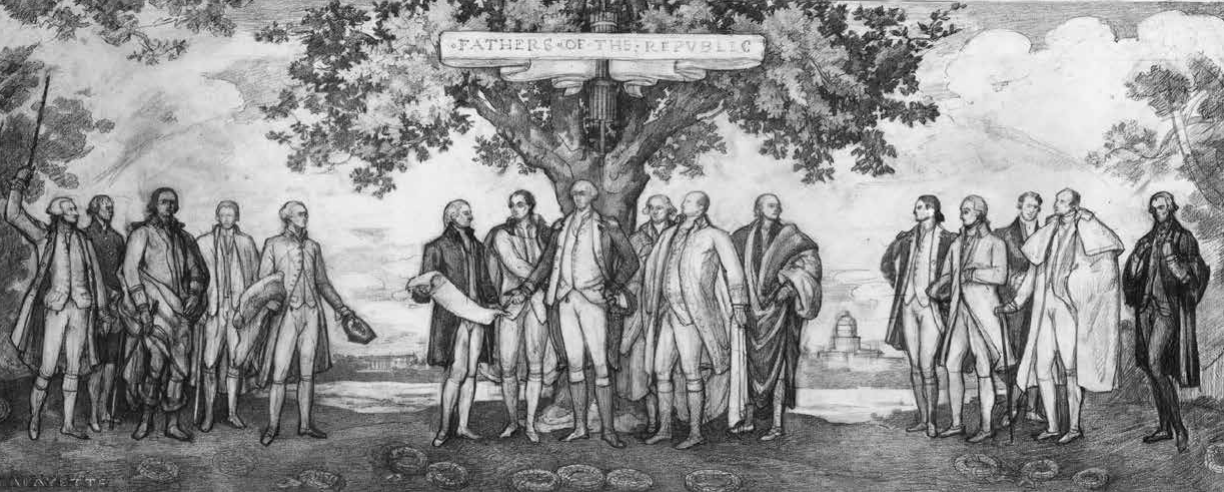

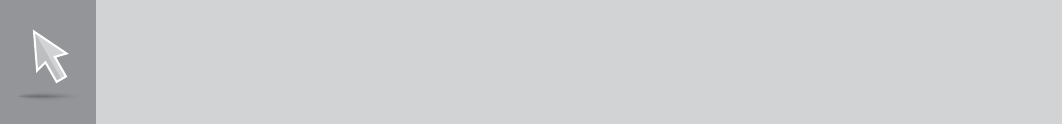

The recomposed Archive Makers:The Constitution presented with the rst-stage studies at the July 26, 1934, commission meeting. Left to right: M. de Lafayette, C. Strong,

G. Mason, J. Dickinson,A. Hamilton, J. Madison, O. Ellsworth, G.Washington, G. Morris, E. Randolph, J. Jay, C. C. Pinckney, J. Monroe, R. King,A Gallatin, J. Marshall.

Spring 2014

THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

AND THE POWER OF THE STATES

On the right side of the mural, primar-

ily, Faulkner represents allegorically the con-

flicts in the Convention over the form of the

new republic’s government.

In the grouping of three men adjacent

to Washington are King, William Paterson

of New Jersey, and Charles Cotesworth

Pinckney of South Carolina. King advo-

cated a “supreme” central government, and

Paterson a government with the states re-

taining considerable power. Additionally,

King supported the Virginia, or large state,

plan for government; Paterson was the archi-

tect of the New Jersey, or small state, plan.

Gen. C. C. Pinckney, paired with Paterson,

shared Paterson’s view on the states’ retain-

ing a role in the government.

e three men in the next group on

the right were strong advocates for a su-

preme central government. George Read of

Delaware, portrayed as an outlier in shadow

at the far right, advocated the extreme ap-

proach of erasing all state boundaries. e

one-legged Gouverneur Morris favored

an aristocracy, reflected in the aristocratic

bearing of his portrait. Hamilton favored

a powerful, almost monarchical, form of

central government with an executive and

senate elected for life, likely symbolized in

his gold cape and partially raised sword. G.

Morris and Hamilton played key roles in the

ratification of the Constitution.

Behind Washington and over his shoul-

ders are George Mason of Virginia and

Benjamin Franklin. Mason and Franklin fa-

vored a plural executive; a singular executive

is personified in Washington.

Supporters of states’ rights are seen through-

out the composition. However, four such

individuals—Luther Martin of Maryland,

Sherman, Gunning Bedford, Jr., of Delaware,

and Abraham Baldwin of Georgia—are clus-

tered at the top of the steps of the portico.

e exposed epaulette on Washington’s

right shoulder, scabbard, and riding boots

(with spurs) present an image of Washington

as commander-in-chief once more. e

cape barely hanging on his shoulders is

reminiscent of portraits of the monarchs

of the time. Together with his facial expres-

sion and stance, the portrayal projects the

dignity of a monarch, which was how the

Congress (particularly the Federalists) pre-

ferred Washington to present himself to the

European powers.

Two of the men discussed in this section—

Martin (who wrote the Supremacy Clause)

and Mason—did not sign the Constitution.

Rutledge’s clothing was typical of the finery

worn by delegates from the southern states.

Faulkner may therefore be using the contrast-

ing clothing of Gorham (from Massachusetts)

in the same way he used Jefferson and John

Adams in the Declaration to distinguish the

two “strains” at the Convention.

Delegates associated with the judiciary are

shown in their robes. Ellsworth and Read

were judges; Wilson was a legal scholar.

Paterson would become an associate justice

of the Supreme Court but is portrayed wear-

ing a style of robe seen in portraits of Chief

Justice John Jay instead of the robe shown in

Paterson’s own portraits.

Gen. C. C. Pinckney is costumed in a man-

ner befitting his rank. e red sash around

Hamilton’s waist, the exposed epaulette, the

riding boots, and officer’s short sword are

consistent with the military rank he held in

the Battle at Yorktown, commander of the

48 Prologue

The rst-stage studies presented at the July 26, 1934, commission meeting. Top: The Declaration features, left

to right, G.Wythe, G. Read, R. Morris, R. Sherman, J.Adams, G. Livingston, B. Franklin,T. Jefferson, S. Adams,

P. Henry, R. H. Lee. Bottom: In the Constitution the individuals portrayed are unchanged from the Archive

Makers Constitution.

light infantry. e gray color of his uniform,

however, was seen only in uniforms worn in

the first year of the War of 1812.

Charles Pinckney’s love of scholarship is

sybmolized in the book he is holding over

his heart. e walking sticks of Gouverneur

Morris and Charles Pinckney are symbolic of

social status. Sherman is portrayed holding his

walking stick in a sinister manner, likely re-

flecting the comment of Jeremiah Wadsworth,

a Connecticut statesman, that Sherman is as

“cunning as the devil, slippery as an eel.”

Finally, Bedford is shown with his left hand

outstretched surreptitiously, likely reflecting

his “foreign influence” statement, “Sooner

than be ruined, there are foreign powers who

will take us [small states] by the hand.”

THE BACK STORY: FAULKNER

IS HIRED, OFFERS SKETCHES

On October 23, 1933, the chief architect

of the National Archives, J. Russell Pope,

recommended the approval of a two-year

contract to hire Barry Faulkner, a noted

American muralist, to paint a mural for

the Exhibit Hall in the planned National

Archives Building.

e contract awarded $36,000 in costs

plus $6,000 for incidental expenses, with all

deliverables due two years later.

e work would be supervised by Pope.

e government was represented on the

contract by Louis A. Simon, the supervis-

ing architect for the Treasury Department.

All work on the murals would need the ap-

proval of both architects. e United States

Commission of Fine Arts would serve in an

advisory capacity.

e team presented expertise in art, archi-

tecture, painting, and sculpture. Faulkner

had trained under and worked with re-

nowned artists and sculptors and was among

the muralists considered to have revolution-

ized decorative painting in America.

By 1933, Faulkner had been commis-

sioned by and completed murals for the

Eastman eater (Rochester, New York),

RCA Building, Rockefeller Center (New

Depicting the Creation of a Nation

York City), and Mortensen Hall of Bushnell

Center (Hartford, Connecticut). Pope had

been the architect for the National Gallery

of Art, the omas Jefferson Memorial, and

the Masonic Temple of the Scottish Rite in

Washington, D.C.

Missing from the team was credentialed

expertise in United States history. is de-

ficiency haunted the project for several

months until the team added J. Franklin

Jameson from the Library of Congress, re-

garded by the chairman of the Commission

of Fine Arts, Charles Moore, as the “dean of

American history.”

Two sketches had been supplied with the

contract. One was titled Archive Makers: e

Declaration and the other Archive Makers: e

Constitution. Both sketches showed a lineup

of persons of importance to the early repub-

lic, set against a purely landscape background.

e sketches did not elicit much reac-

tion from the commission. According to the

minutes from the January 1934 meeting, the

commission commented, “you get as much

life and congruity in your Constitution as you

have done in your Declaration, that mostly

front views are shown” and that “Washington

ought to be doing a little something.”

FAULKNER PREPARES SKETCH

“FATHERS OF THE REPUBLIC”

In the months that followed, Faulkner

worked on and completed a new

Constitution, retitled Fathers of the Republic

and the first-stage studies required by the

contract. e completed Fathers sketch

demonstrates a major rethinking of organi-

zation. Washington is clearly the central fig-

ure, and the men are clustered. Monroe had

been deleted from the original sketch; Albert

Prologue 49

Spring 2014

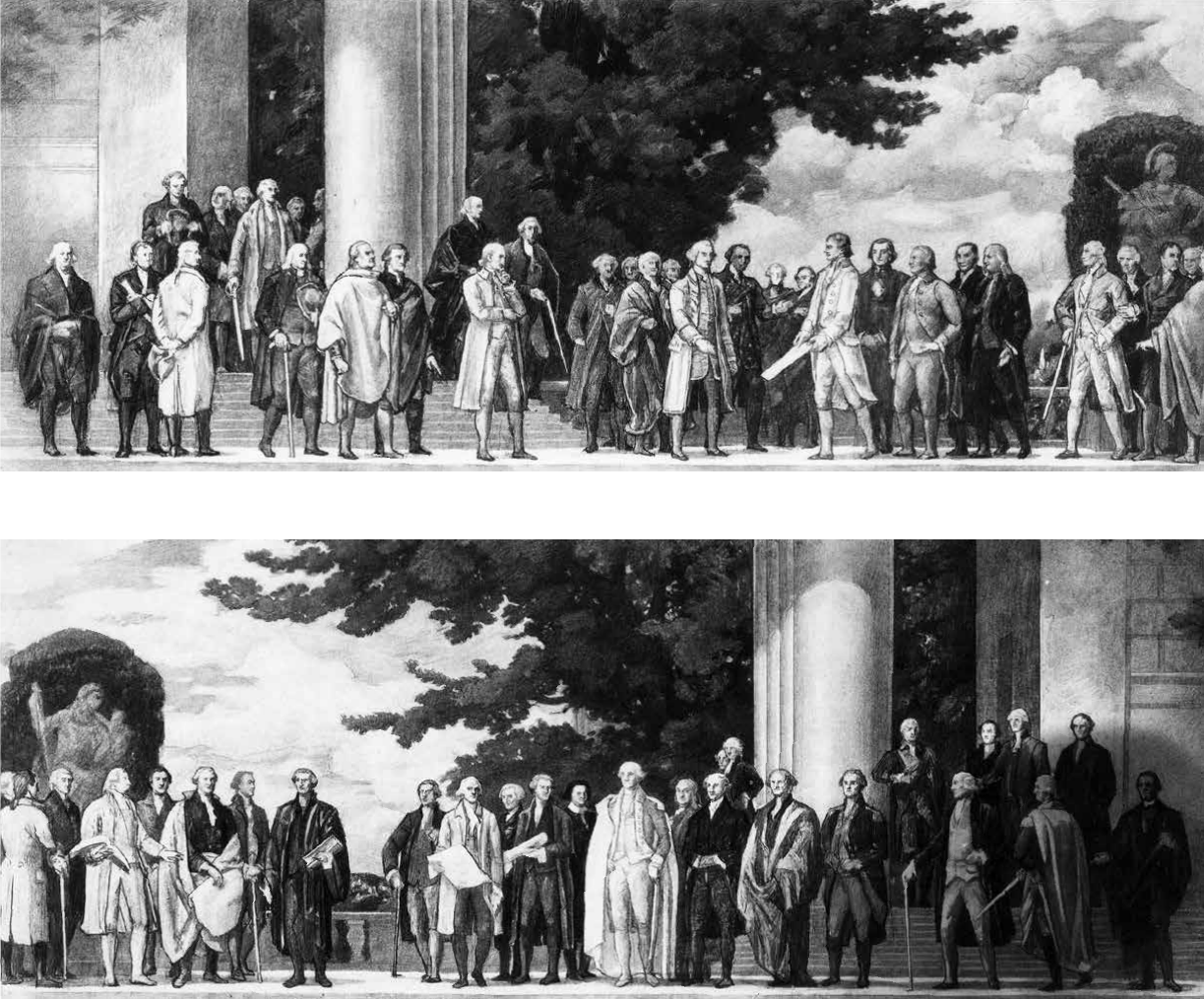

Expanded studies showing men through Lincoln and his time, based on recommendations made by Charles Moore, with statues representing war (Declaration) or

peace (Constitution). Top: Declaration. Left to right along the base are H. Clay,A. Gallatin,A. Lincoln, J. Monroe, R. Sherman, G. Livingston, J.Adams, J. Hancock, J. Dickinson

(obscured), R. Morris,T. Jefferson, S. Adams, P. Henry, B. Franklin. By the column, extreme left in front, B. HarrisonR. H. Lee; in back, 3 unknown. At top of steps, to

right of column,from left: G.Wythe,W. Floyd.Bottom: Constitution, left to right: unknown, J.Wilson, O. Ellsworth, C. Pinckney (in back), J. Madison, E. Gerry (in back), S.

Johnson, G. Mason (behind Washington), G.Washington, B. Franklin (behind Washington), R. King,W. Paterson, C. C. Pinckney, G. Morris,A. Hamilton,W. Read.At the

left of the column are W. R. Davie and J. Langdon, and at right of column, left to right, are L. Martin, R. Sherman, B. Gunning,A. Baldwin.

Gallatin (who was treasury secretary under

Jefferson and Madison), the Marquis de

Lafayette, Gen. C. C. Pinckney, and Celeb

Strong had been added. Based on Simon’s

comments that “it was limited to the early

days of the Republic” and “the figures would

be disproportionately large,” this sketch was

not considered further.

e first-stage studies had been mounted

on the “walls” of a partial cutaway scale

model of the Exhibit Hall. e commission

used black-and-white photographs of the

construct to evaluate both the artistry and

how well the murals would integrate with

the decorations in the hall.

One first notices the change in back-

grounds to a mix of landscape and architec-

ture. “e [new] background would inte-

grate well with the stark architecture of the

Exhibit Hall, and would impart a feeling of

distance and space; and the alternative, an

architectural background, would require the

use of Independence Hall, which would be

monotonous across two panels,” Faulkner

later explained.

e positions of the men in the first-stage

Declaration differ from the original sketch.

Two men had been added, Patrick Henry

and another whose identity is lost to his-

tory. For the Constitution, it is almost as

if the lineup of men in the original sketch

had been cut out and pasted into a new

background.

50 Prologue

e commission, in a letter to Simon on

July 27, explained that they “agree[d] that

a more comprehensive treatment of the

matter was desirable in connection with

the wide range of materials to be housed

in the Archives Building.” Simon forward-

ed a copy of this letter with his comments

to Pope the following day. It is clear from

Pope’s reply to Simon that he understood

the commission’s concern to mean that the

murals “should be a subject related to this

particular building.”

Subsequent attempts by Faulkner and

Pope to obtain additional information on

the commission’s evaluation of the first-stage

studies failed. Still, Faulkner forged ahead,

completing a revised set of first-stage studies.

rough a process of addition and deletion,

the number of men in his prior first-stage

Declaration had been increased by four and

now included John Hancock.

HISTORICAL SCOPE EXTENDED,

BUT COMMISSION SAYS “NO”

Faulkner submitted the revised studies for

presentation at the commission’s September

17 meeting. He introduced his new studies

as the signers of the Declaration and the sign-

ers of the Constitution (even though Patrick

Henry was included in the Declaration, John

Marshall and Lafayette in the Constitution,

and James Monroe in both).

e lack of comprehensiveness was

brought up again. Moore proposed as a solu-

tion that “one of the panels be dedicated to

the founders of the Republic and the other

to Abraham Lincoln and his time.”

Viewing Moore’s proposal positively,

Faulkner developed two lists accommodat-

ing the portrayal of up to 19 men in each

study, with each list based on one of two se-

lection models for each subject.

e first model was “to confine the sub-

ject matter to men of primary and sec-

ondary importance who wrote or signed

the Declaration and the Constitution or

who were intimately concerned with the

two documents, but not members of the

Depicting the Creation of a Nation

Conventions: like Patrick Henry, Otis, John

Jay and Marshall.”

e second was “to enlarge the scope of

the subject, introducing great statesmen

up to the time of Jackson or even Lincoln,

but with the stress still on the men of the

Constitution and Declaration.”

Based on his lists, Faulkner composed

a new set of studies and submitted them

to Moore’s office on September 22. What

is immediately apparent in the new stud-

ies are features from the Fathers sketch.

Specifically, men are distributed through-

out the composition and are organized into

clusters. Additionally, in the Constitution,

Washington is now the central figure.

Twenty-one men are portrayed in the

Declaration, 10 more than in the prior study.

Henry Clay, Gallatin, and Lincoln had been

added. Twenty-two men are portrayed in

the Constitution, 11 more than in the prior

study. With the exception of the statue and

a few missing persons to the left of Charles

Pinckney, the Constitution resembles the

fully evolved mural.

Unbeknownst to Faulkner, Moore had

drafted a letter to Pope on September 25, a

day before receiving Faulkner’s new studies.

Moore provided a clear insight into the com-

mission’s vision for the murals: “us, oppor-

tunity is offered, as never since the Rotunda

of the Capitol was decorated, to express in

mural work the significance of the place of the

building itself in the history of the country.”

e letter also stated that the commis-

sion found the original first-stage studies

to be inadequate, lacking unity and needed

focal character; and recommended their

disapproval.

Moore’s draft letter was not delivered to

Pope until mid-October, after Moore had

personally met with him to discuss the status

of the contract.

At Moore’s request, he and Pope met in

Newport, Rhode Island, on October 10

and 11 to discuss the status of the murals.

Faulkner was brought into the discussion by

phone. Pope and Moore informally agreed

that Faulkner needed to discard his prior

studies and prepare an entirely new set.

According to the report on the meeting,

“two new panels should be prepared for

submission, the first panel is to present the

Declaration of Independence, the second,

the Constitution, general terms to connote

the spirit in which these historic documents

were produced.”

e fact that the actual Declaration and

Constitution were at the Library of Congress

was brought up twice at the commission

meetings. Moore remarked that “when lay-

ing the cornerstone for the new Archives

building, President Hoover referred to them

saying that they would be deposited in the

new Archives building.”

Not until December 13, 1952, 16 years

after the opening of the building, would

the two documents be transferred to the

National Archives Building and enshrined

in their display cases.

HISTORIAN JAMESON OFFERS

HELP ON WHOM TO DEPICT

Faulkner requested Moore’s help in assem-

bling an authoritative list (25 men for each

picture) for a new set of studies, and Moore

suggested that Faulkner contact Jameson for

assistance, noting that he had already asked

Jameson to “put his mind to the subject.”

Moore continued: “First, in the

Declaration, only half the signers can be rep-

resented. erefore, the selection of twenty-

five out of fifty men should have a basis in

some broad generalization. Second, it has

seemed to me that in a central group, the con-

trasting puritan and cavalier strains, would

give the artist a great opportunity in cos-

tume and type—the Lees and John Adams.

ird, I do not see why the buildings peep-

ing out at the ends should not be Georgian.

Fourth, the Declaration stood for war, the

Constitution for peace. Is there not an op-

portunity to work this feeling into the skies?

Fifth, Washington’s character produced the

harmony in the Convention which brought

the Constitution into being.” Moore closed

Prologue 51

Spring 2014

by commenting “I suppose Madison had

most to do with the text and details of the

Constitution, and that Hamilton and John

Adams had most to do with its ratification.”

By November 16, Jameson had provided

Faulkner with a list of possible men to por-

tray and a rationale for his selections. He

advised including in each study at least one

person from each state, lest “there be outcries

if there was any one [state] that did not have

a figure in the painting.” For the Declaration,

“John Hancock as well as omas Jefferson

and his committee needed to be included.”

Jameson’s Declaration list named

Hancock, Jefferson, and 11 men from the

remaining states and named 10 additional

men in order of preference “should the need

arise for additional.” He also provided a list

of 19 men for the Constitution.

FAULKNER USES COMMITTEES

TO DETERMINE GROUPINGS

Using Jameson’s lists plus some additional

men, Faulkner submitted a new set of stud-

ies to the commission. In his presentation

note, Faulkner clarified that “the Declaration

symbolized war, the Constitution peace. His

committee groupings show thirteen in one

group to represent the thirteen original colo-

nies; and only Benjamin Franklin and one or

two other statesmen had been duplicated in

each of the sketches.”

Faulkner explained that the basis for his

groupings was that of the committees appoint-

ed in the two Conventions: “e Committee

of the Grand [Great] Compromise . . . ,

the Committee for the first draft of the

Constitution; and the Committee for the fi-

nal draft of the Constitution. e groups are

centered on Washington where men served

on more than one committee. Finally, a few

important men had been included, such as

To learn more about

General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and

his cousin Charles Pinckney, who did not

serve on these committees.”

Two committees are represented in the

Declaration, Faulkner continued: “One is

comprised of Jefferson and the Committee

on the Declaration [the Committee of Five]

with Hancock and Harrison. e second,

the committee for drafting the Articles of

Confederation, is represented because it was

closely linked with the Committee on the

Constitution and was appointed at the same

time; the Articles were useful as a basis for

some parts of the Constitution and help link

the two subject matters; and the Committee

gave a man from each state. R. H. Lee is

positioned prominently in the Declaration

because of his motion for independence.

Finally, men not on any committee are by

themselves.”

Twenty-seven men were portrayed in the

new Constitution, grouped the same as in the

fully evolved mural. irty-three men were

portrayed in the new Declaration.

Where Faulkner had placed statues rep-

resenting war (Declaration) and peace

(Constitution), the commission suggested us-

ing standards of the colonies “to represent the

dangerous situation of the men who took part

in the Declaration of Independence”; and

“trophies of victory and the Stars and Stripes”

for the Constitution. Overall, the commis-

sion evaluated the new studies favorably.

Following the December meeting of the

commission, Faulkner set to work incorpo-

rating their recommendations into a final set

of studies. In a letter to Moore, he explained

that the basis for the groupings remained the

same as for the prior set of studies.

e sculpted figures in the prior set of stud-

ies, he wrote, had been replaced with “known

Revolutionary battle flags in the Declaration;

and for the Constitution, the State flags of the

thirteen original colonies in the symbol of

the Union Not mentioned were the realistic

gathering storm clouds now appearing in the

sky of the Declaration, addressing Moore’s

suggestion to represent “war” in the skies.

FINAL VERSION APPROVED;

MURALS COME TO ARCHIVES

With his final studies, Faulkner had pro-

duced two murals that were historically

consistent throughout. is even applies to

the architecture, which is representative of

the type found in early Greek democracies.

Additionally, the columns are intended to be

“pillars of democracy.”

e individual elements of each mural

are integrated, and through the Articles of

Confederation, Faulkner has linked the two

murals historically.

Finally, through the use of costuming,

Faulkner “covertly” enhanced the historic

scope of the murals from the early days of

the Republic through the Revolution and

the War of 1812. In the storm clouds in

the Declaration one can see Lincoln’s profile

turned on its side. e Lincoln image extends

the historical period into the Civil War, mak-

ing the murals better serve as frontispieces

for the contents of the Archives building.e

commission officially approved Faulkner’s lat-

est studies on January 21, 1935.

After completing the individual drawings

of the figures and incorporating them into

the cartoons, Faulkner moved out of his stu-

dio and rented space in the attic over New

York’s Grand Central Station. Here he built

two walls 40 feet long by 18 feet high facing

each other to support the canvases.

By December 20, the completed cartoons

had been enlarged to full size by photogra-

phy and traced onto the canvas. Faulkner

• Faulkner’s role in designing camouflage for U.S. troops in World War I, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/spring/.

• Conservation work given to the Faulkner murals, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2003/spring/.

• Where the Declaration and Constitution were kept before coming to the Archives, go to www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/winter/.

52 Prologue

Recomposed expanded studies based on listings provided by J. Franklin Jameson and provided at the December 3, 1934, commission meeting. Top: Declaration.

Bottom: Constitution.

provided 24 inches of empty canvas to al-

low for possible differences between the

space allotted for the murals in the plans

and the actual space on the curved walls of

the Exhibit Hall.

e commission visited Faulkner’s stu-

dio on March 12, 1936, to see Faulkner’s

compositions—now in full color. At that

time, Faulkner informed the commission

he had approximately six more months of

work on details; they were completed as

promised in September.

e completed murals were rolled up on

wooden drums, boxed, and shipped to the

National Archives in Washington. Faulkner

and one his painters, John Sitton, and pa-

perhanger Fred Crittendon accompanied

the murals. By October 15, the murals had

been installed on the Rotunda walls, and the

artists painted in the areas where they had

extra space. e first public viewing was in

early November.

One year after their installation, the

painted surface of each mural was complete-

ly varnished using beeswax and varnish in

turpentine followed by buttermilk in water.

Faulkner instructed that the treated surface

of the murals not be touched and explained

that the pictures could be expected to stay in

good condition for 40 or 50 years.

Depicting the Creation of a Nation

Prologue 53

Spring 2014

MURALS RECEIVE CONSERVATION

TREATMENT AFTER 60 YEARS

As Faulkner predicted, the murals did stay

in decent condition for about 40 years. By

1986, however, they were exhibiting buck-

les and bulges due to the crumbling of the

plaster behind them and deformation of the

canvas. In 1999, needed conservation work

for the murals was officially designated as a

“Save America’s Treasures” project. e proj-

ect was timed to coincide with the first-ever

top-to-bottom renovation of the National

Archives Building, during which it would be

closed to visitors. Conservation of the murals

was completed by November 2002, and they

were reinstalled on the Rotunda walls.

•

e story of these historic murals, which

enhance the meaning of the documents on

display just below them, is fascinating in it-

self, for it sheds light on the differing inter-

pretations about the roles of many of those

we call the “Founding Fathers.” How each

man is depicted tells a lot about him and the

beliefs he brought to the Pennsylvania State

House in 1776 or 1787 to debate either the

Declaration or the Constitution.

Although Faulkner kept the main visual

focus of the murals on a single subject, ei-

ther the Declaration of Independence or

the Constitution, he was able to inject other

messages.

Taking into consideration the possible

symbolic meanings of the “Lincoln” cloud

(Civil War) and Hamilton’s gray uniform

(War of 1812), Faulkner appears to have

used costuming and the sky to expand the

scope of history represented from the early

days of the Republic.

In that sense, the murals span the arc of

our nation’s early history.

P

N S

e author is grateful to the following indi-

viduals for their assistance and advice in retrieval

of information and documents used to assemble

this article: Richard Blondo and the staff of the

Research Libraries at the National Archives and

Records Administration, Washington, D.C., and

College Park, Maryland; Emily Moazami of the

Photographic Archives, Research and Scholars

Center, Smithsonian American Art Museum,

Washington, D.C.; Marisa Bourgoin, Richard

Manoogian, and Margaret Zoller of the Archives

of American Art, Washington, D.C.; Doug

Copeley, New Hampshire Historical Society;

and Alan Rumrill, Historical Society of Cheshire

County, Keane, New Hampshire.

Summary descriptions of Faulkner’s rationale

for the organization and content of the murals, as

well as their painting and installation, were found

in the autobiography Barry Faulkner: Sketches from

an Artist’s Life (Dublin, New Hampshire: William

L. Bauhan, 1973); and Alan F. Rumrill and Carl B.

Jacobs, Jr., Steps to Great Art: Barry Faulkner and the

Art of the Muralist (Keene, NH; Historical Society

of Cheshire County, 2007). A more detailed de

-

scription was provided in a transcript of a presenta-

tion made in 1957 by Faulkner to the Keene (N.H.)

Daughters of the American Revolution, in the Barry

Faulkner Papers in the Archives of American Art,

Research Collection, Series 3: Writings: “Archives,”

1957 (www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/

Archives--282658).

e contract hiring Faulkner to paint the

murals is in the Records of the Public Building

Services, Record Group (RG) 121, National

Archives at College Park, Maryland.

e stages in the evolution of the murals from

their original sketches through their painting and

installation are captured in the U.S. Commission

of Fine Arts correspondence and meeting minutes

in the Records of the Commission of Fine Arts,

1893–1981, RG 66.

Photographic reproductions of the sketches and

studies Faulkner submitted to the Commission for

review are in the Peter A. Juley & Son Collection

at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Only

three of the reproductions carried identifications

of the portrayed individuals, and none of the

reproductions are dated. Fortunately, a “Rosetta

Stone” for matching portrayals with names in the

form of listings was included with a letter from

Faulkner to Charles Moore of September 20,

1934, in Record Group 66.

e process of conserving the murals is sum

-

marized in Richard Blondo, “Historic Murals

Conservation at the National Archives” in

Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and

Records Administration 44 (Fall 2012): 26–29.

Interpretation of the murals proved to be a

daunting task. Faulkner’s explanations to the com

-

mission on his murals (Records of the Commission

of Fine Arts, RG 66) contain only the core elements

of the organization of his compositions. With the

exception of the differences in clothing of Jefferson

and Adams in the Declaration, the records do not

provide a basis for the poses and costuming in the

individual “portraits” and a rationale for the color

schemes promised to the commission.

Further information about the organization of

the Declaration mural’s composition, roles of in

-

dividual delegates, and personal and professional

lives were was found primarily in the Journals of the

Continental Congress, 1724–1789, ed. Worthington

Chauncey Ford, et al. (Washington, D.C.: 1904–

37), vol. 4, and Reverend Charles A. Goodrich, Lives

of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, 2nd

ed. (New York: omas Mather Publisher, 1832).

For the Constitution mural, the same type of

information, as well as the members of the com

-

muttee writing the Articles of Confederation

came from Max Farrand, ed., e Records of the

Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press, 1911), vols. 1–3; Catherine

Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: e Story

of the Constitutional Convention May to September

1787 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company,

1966); and Farrand, e Fathers of the Constitution:

A Chronicle of the Establishment of the Union (New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1921); and oth

-

er articles and books about individual delegates.

e comment on Sherman’s character is a direct

quote from “Letter from Jeremiah Wadsworth to

Rufus King,” June 3, 1787, in Farrand’s Records of

the Federal Convention of 1787.

e commentary on Alexander Hamilton’s mili

-

tary uniform is based on information from James

L. Kochan, e United States Army, 1812–1815

(Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing, 2000); and

David Cole, “Survey of U.S. Army Uniforms,

Weapons and Accoutrements,” (www.history.army.

mil/html/museums/uniforms/survey_uwa.pdf ).

Lester S. Gorelic volunteers as a do-

cent at the National Archives Building

in Washington, D.C. He retired

in 2009 from the National Cancer

Institute, Rockville, Maryland, where most recently as

program director, he developed and managed portfolios

of federal grants supporting the research training and re-

search career development of cancer researchers. He holds

a Ph.D. in chemistry from the University of Chicago.

© 2014 by Lester S. Gorelic

Author

54 Prologue