PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

1

Original research

Gun violence restraining orders in California, 2016–

2018: case details and respondentmortality

Veronica A Pear ,

1

Rocco Pallin,

1

Julia P Schleimer ,

1

Elizabeth Tomsich,

1

Nicole Kravitz- Wirtz ,

1

Aaron B Shev,

1

Christopher E Knoepke ,

2,3

Garen J Wintemute

1

To cite: PearVA, PallinR,

SchleimerJP, etal. Inj Prev

Epub ahead of print: [please

include Day Month Year].

doi:10.1136/

injuryprev-2022-044544

► Additional supplemental

material is published online

only. To view, please visit the

journal online (http:// dx. doi.

org/ 10. 1136/ injuryprev- 2022-

044544).

1

Department of Emergency

Medicine, University of

California Davis School

of Medicine, Sacramento,

California, USA

2

Adult and Child Consortium

for Outcomes Research and

Delivery Science, University

of Colorado Denver School of

Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA

3

Division of Cardiology,

University of Colorado School of

Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA

Correspondence to

Dr Veronica A Pear, Department

of Emergency Medicine,

University of California Davis

School of Medicine, Sacramento,

California, USA; vapear@

ucdavis. edu

Received 3 February 2022

Accepted 1 April 2022

© Author(s) (or their

employer(s)) 2022. Re- use

permitted under CC BY- NC. No

commercial re- use. See rights

and permissions. Published

by BMJ.

ABSTRACT

Background Gun violence restraining orders (GVROs),

implemented in California in 2016, temporarily prohibit

individuals at high risk of violence from purchasing or

possessing firearms and ammunition. We sought to

describe the circumstances giving rise to GVROs issued

2016–2018, provide details about the GVRO process

and quantify mortality outcomes for individuals subject

to these orders (’respondents’).

Methods For this cross- sectional description of GVRO

respondents, 2016–2018, we abstracted case details

from court files and used LexisNexis to link respondents

to mortality data through August 2020.

Results We abstracted information for 201 respondents

with accessible court records. Respondents were

mostly white (61.2%) and men (93.5%). Fifty- four

per cent of cases involved potential harm to others

alone, 15.3% involved potential harm to self alone and

25.2% involved both. Mass shooting threats occurred

in 28.7% of cases. Ninety- six and one half per cent of

petitioners were law enforcement officers and one- in-

three cases resulted in arrest on order service. One- year

orders after a hearing (following 21- day emergency/

temporary orders) were issued in 53.5% of cases. Most

(84.2%) respondents owned at least one firearm, and

firearms were removed in 55.9% of cases. Of the 379

respondents matched by LexisNexis, 7 (1.8%) died after

the GVRO was issued: one from a self- inflicted firearm

injury that was itself the reason for the GVRO and the

others from causes unrelated to violence.

Conclusions GVROs were used most often by law

enforcement officers to prevent firearm assault/homicide

and post- GVRO firearm fatalities among respondents

were rare. Future studies should investigate additional

respondent outcomes and potential sources of

heterogeneity.

INTRODUCTION

Firearms are the most common means of homi-

cide and suicide in the USA.

1

Many acts of firearm

violence are preceded by implicit or explicit threats,

including two- thirds of public mass violence.

2

Despite these warning signs, law enforcement offi-

cers in most states cannot remove firearms from

individuals at risk of violence who are not already

prohibited from possessing firearms. Extreme risk

protection order (ERPO) laws were created to fill

this legal gap.

Called gun violence restraining orders (GVROs)

in California, these laws provide a civil mechanism

to temporarily prohibit individuals from possessing

and purchasing firearms and ammunition during

periods of heightened risk of self- or other- directed

harm.

3

As of May 2022, 19 states and the District of

Columbia have passed an ERPO- type law, the vast

majority of which were enacted in the past 5 years.

These orders show promise for preventing

suicide

4 5

and possibly mass shootings,

6

but imple-

mentation has been slow and variable across

jurisdictions in California.

7

In addition, there are

legitimate concerns about whether ERPOs, which

can provide a life- saving, non- criminal solution to

threats of firearm violence, are being used in ways

that exacerbate racial and class- based inequities.

8–10

We previously presented demographic informa-

tion on individuals subject to GVROs—hereafter,

‘respondents’—in California over the first 4 years

of implementation using the California Depart-

ment of Justice’s (CA DOJ) restraining order data.

7

Investigating case circumstances, respondent risk

factors and violent outcomes provides a richer

understanding of GVRO implementation and use

as well as a foundation for identifying emerging

inequities. This is particularly important now that

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

⇒ Prior research suggests that risk- based

temporary firearm removal laws similar to

gun violence restraining orders (GVROs) have

been primarily used to prevent firearm suicide,

for which they appear to be effective tools.

Effectiveness for preventing interpersonal

violence is unknown.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

⇒ In California, GVROs have been mostly used

in cases of threatened interpersonal violence.

No respondent deaths were caused by

violence occurring after the GVRO was issued,

suggesting that the law may be effective in

preventing fatal firearm violence.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH,

PRACTICE OR POLICY

⇒ Findings can inform policymakers and

practitioners about how to best design

and implement GVROs and may also help

researchers generate hypotheses regarding

GVROs’ potential for multimodal violence

prevention.

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from

PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

2

Original research

President Biden has called on Congress to incentivise state adop-

tion of ERPO laws and to pass a national law.

11

The aim of the current study is to characterise GVRO cases

in California in the first 3 years of implementation, 2016–2018.

Using court case files and mortality data, we describe the circum-

stances that gave rise to these GVROs, provide details about the

GVRO process and assess respondent mortality outcomes. We

also compare demographic characteristics of respondents with

those of the general population and the population of legal

firearm owners (to whom GVRO respondents may be more

similar) in order to identify whether any groups are conspicu-

ously over- represented or under- represented. Findings will be

of interest to policymakers, practitioners involved with GVRO

implementation and firearm violence researchers.

METHODS

GVRO process

During the study period, law enforcement, family and house-

hold members were permitted to petition for a GVRO. There

are three types of GVROs: emergency orders, lasting 21 days

and available only to law enforcement; temporary orders, also

lasting 21 days but available to all petitioners; and orders issued

after a hearing, which lasted for 1 year during the study period

(and up to 5 years beginning September 2020). Respondents

are required to relinquish their firearms and ammunition to

law enforcement or a licensed firearm dealer within 24 hours

of being served an emergency or temporary order. When a

short- term order is issued, a hearing is scheduled 21 days later,

wherein a judge determines whether the respondent still poses a

danger to themselves or others and rules on whether the order

should be extended, terminated or let to expire.

Data collection

We identified all respondents to GVROs filed 2016–2018 with

data from the California Restraining and Protective Order

System provided by CA DOJ. We used this information to request

case records from individual county courts across the state. We

completed these requests in November 2019 and received the

last court file in March 2020.

We determined whether respondents were alive in the study

period by querying LexisNexis Risk Solutions in August 2020.

Cause of death was determined from death certificates from the

California Department of Public Health (received in June 2021).

Mortality data were linked to GVRO data using respondent

name and date of birth.

Measures and analysis

From the court documents, we abstracted information on

respondent demographics, circumstances resulting in the GVRO,

respondent risk factors, the GVRO process, and firearm access

and removal. We used Microsoft Forms to abstract basic case

details from the GVRO forms and Dedoose qualitative software

to abstract information from narratives found in the court docu-

ments. Although they vary in length and detail, case narratives

are always provided by the petitioner, occasionally by other

parties (eg, in supporting documents such as police reports) and

rarely by the respondent (in a formal response to the order). Our

codebook is included as online supplemental emethods.

A small team of analysts trained and oversaw two student

assistants, who carried out the abstraction. Abstractors double

coded all cases for the GVRO forms abstraction and a random

20% sample for the case narrative abstraction, crosschecking

their coding for consistency. After double coding these cases, the

abstractors had reached consensus, allowing for single coding of

the remaining narratives. Abstractors met with team members

weekly to discuss questions, resolve discrepancies and refine the

codebook.

We compared the demographics of respondents with two

groups. While respondents need not have firearm access to

qualify for a GVRO, we found that, in practice, they are very

likely to be firearm owners (see the Results section). We, there-

fore, compared them to firearm owners in California using

state- representative data from the 2018 California Safety and

Wellbeing Survey.

12

To provide broader context, we compared

them with the general state population using data from the

American Community Survey.

We used descriptive statistics to summarise respondent and

case details. Information provided in case narratives varied and

was especially sparse in emergency GVROs. As a result, we could

often only determine whether a given code was present in the

narrative, and we cannot infer from its absence that it was absent

in fact. Accordingly, we included all cases in the denominator

when calculating percentages, including those with missing

information. Thus, estimates represent the statistical floor (ie,

the lowest estimate consistent with the data). Information on

missingness is presented in online supplemental etable 1.

Analyses were done in R (V.4.0.2), Stata (V.15.1) and Dedoose

(V.8.3). This study was approved by the University of California,

Davis Institutional Review Board. Neither patients nor the public

were involved in the conduct of this study.

RESULTS

We requested court records for all 413 GVRO respondents and

received 218 (online supplemental etable 2). The vast majority

(94.4%) of files not received were for cases in which an emer-

gency order was the most recent GVRO issued, which courts

usually could not locate. Emergency orders are used by officers

in the field and issued by a judge remotely. They are single- page

petitions with extremely limited case details and are commonly

filed with the petitioning law enforcement agency rather than

the court, making them particularly difficult to obtain. Seven-

teen respondents without GVRO forms in their court records

were dropped from analysis. We coded a total of 202 cases for

201 respondents. Respondents with abstracted records tended

to have more recent GVROs than those without, but they were

otherwise similar (online supplemental etable 3).

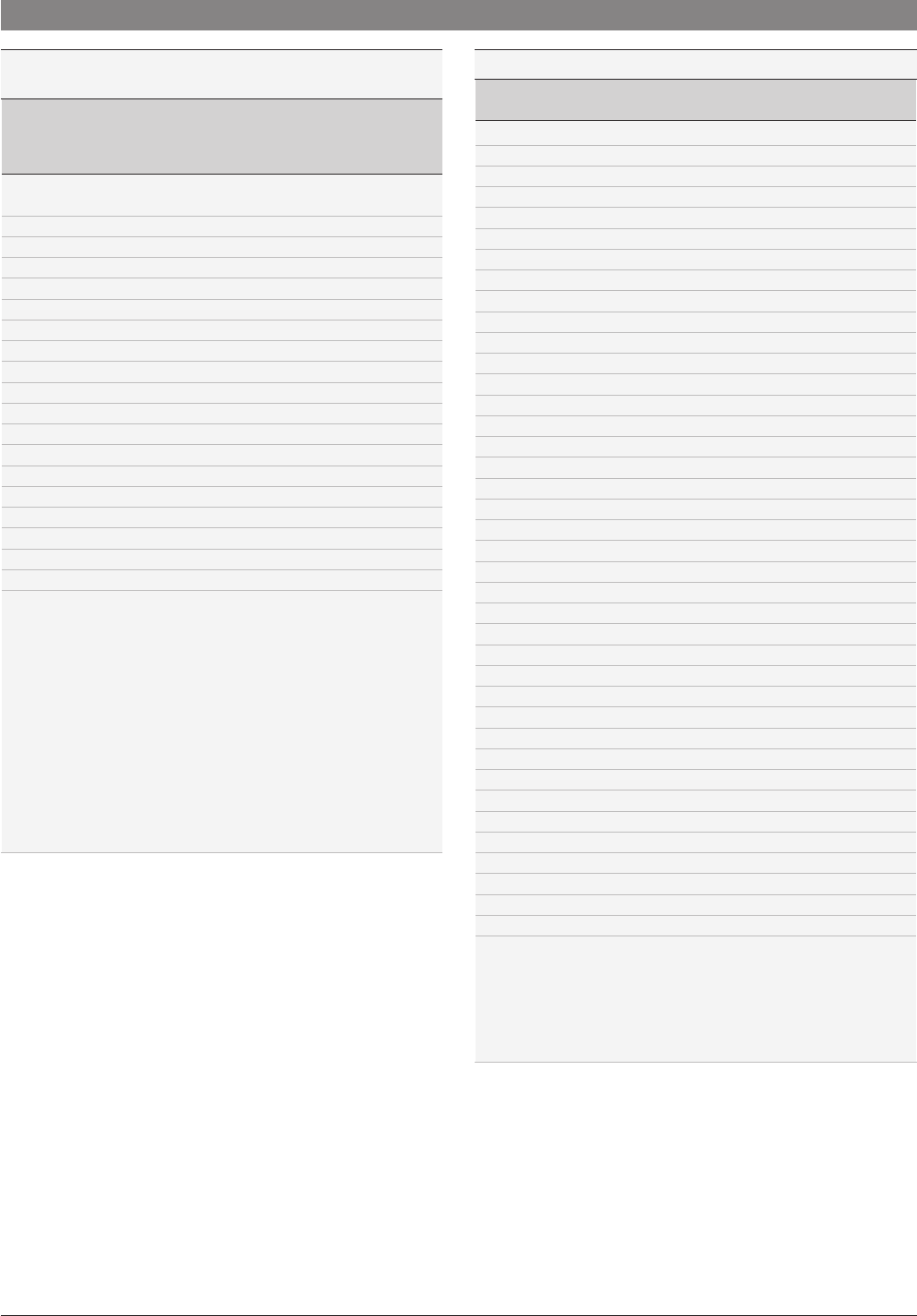

Respondent demographics

GVRO respondents were younger (median age: 39 years) and

more likely to be men (93.5%) than other firearm owners in

the state and the state population (table 1). The racial/ethnic

distribution of GVRO respondents was mostly similar to that

of the statewide firearm owning population, though differences

in reporting did not allow for comparison of Asian Americans.

Black individuals constituted a larger proportion of respondents

(10.0%) than firearm owners overall (4.4%). At least 9.5% of

respondents were veterans, which is about two times the state-

wide average (5.4%) but only one- third of the estimate for

firearm owners (29.2%).

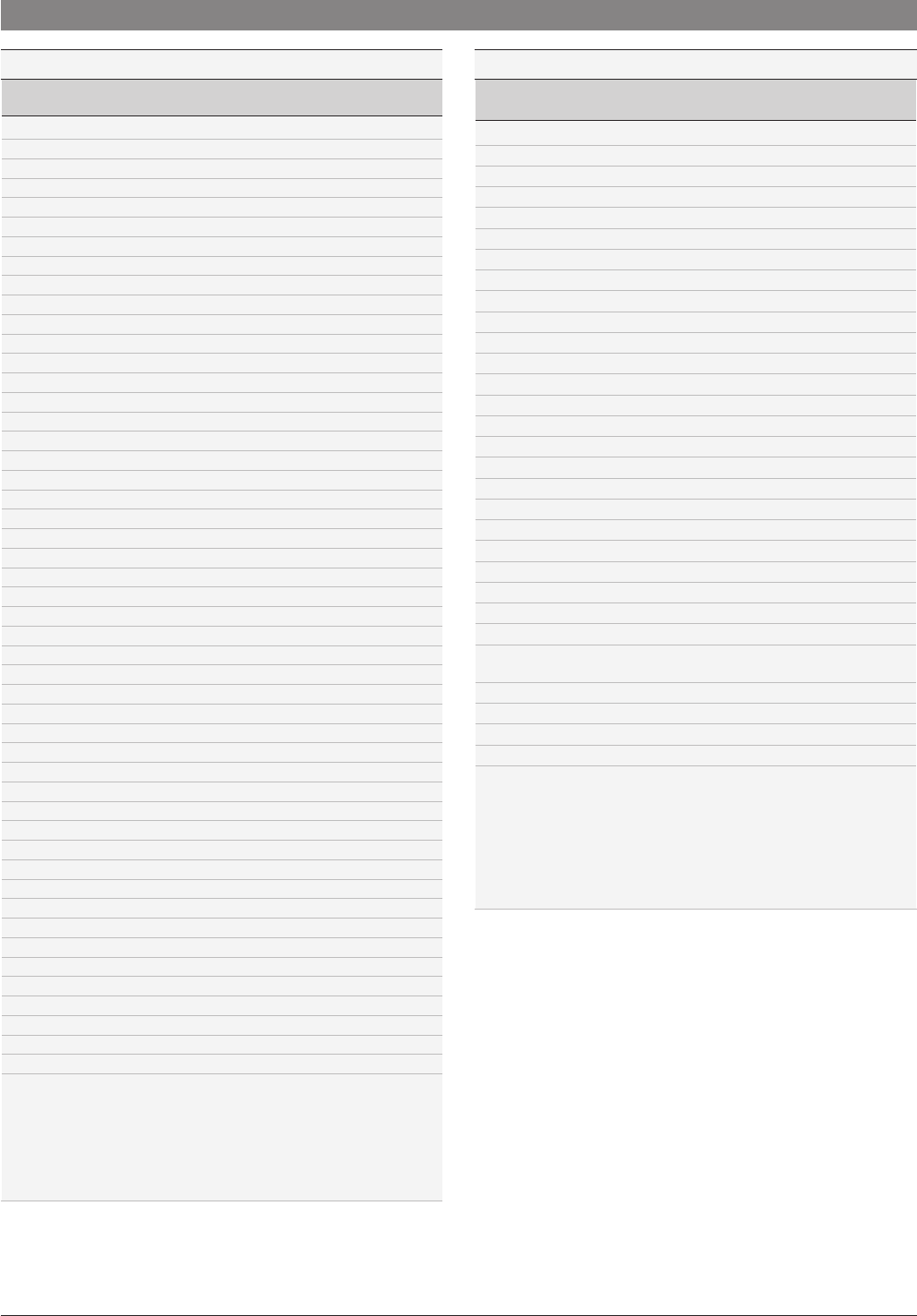

Case circumstances

Most (54.0%) cases involved a documented threat of harm to

others alone, 15.3% involved a threat of harm to self alone and

25.2% included threats of both other- directed and self- directed

harm (table 2). Among the nearly 80% of cases involving any

other- directed threat, 29.4% included threats to intimate

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from

PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

3

Original research

partners and 20.6% included threats to other family members.

Most threats were behavioural (55.4%) and/or verbal (51.5%),

and just over one- third of threats involved brandishing or using

a firearm. Slightly more than one- in- four cases involved threat-

ened mass shootings (ie, a threat to shoot an unspecified number

of people or ≥3 people other than oneself), including all six

cases involving minors (who, in all cases, targeted schools).

Nearly 60% of inciting events took place at a private residence

and 24.3% took place at a public venue (including workplaces

and schools).

We identified many known or hypothesised risk factors for

violence in case narratives (table 3). The most common was

substance use, including drugs and/or alcohol (34.2% of cases),

which directly related to the GVRO inciting event in about a

quarter of cases. The next most common risk factor was a loss

or relationship problem relating to an intimate partner, which

appeared in 22.8% of cases. Mental illness (indicated by a named

diagnosis in the case file)—a risk factor primarily for suicide—

appeared in about 20% of cases, as did prior police contact

resulting in arrest. Information on prior violent behaviour was

less common, ranging from 5.4% with a history of self- harm to

10.4% with a history of intimate partner violence perpetration.

Process details

Over 95% of petitioners were law enforcement officers (table 4).

Petitioners often cited evidence obtained from interacting with

the respondent (50.0%) or information provided by the respon-

dent’s family members (32.7%), significant other (27.7%) or

bystanders (22.3%) in the petition. At the time of police contact

Table 1 Characteristics of GVRO respondents, firearm owners and

the state population

GVRO

respondents

(2016–2018,

n=201)*

Firearm owners

18+ (CSaWS 2018,

n=429)†

California

population 18+

(2016–2018

average)‡

Age, med (25th–

75th pctl)

39 (28–52) 57 (45–67) 45 (31–60)

Minors, n (%) 6 (3.0) NA NA

Gender, n (%)

Male 188 (93.5) 301 (72.9; 66.8–78.3) 14 930 504 (49.3)

Female 13 (6.5) 128 (27.1; 21.7–33.2) 15 363 490 (50.7)

Race/ethnicity, n (%)

White 123 (61.2) 318 (64.1; 56.3–71.2) 12 347 188 (40.8)

Hispanic 35 (17.4) 71 (20.4; 14.6–27.8) 10 653 363 (35.2)

Black 20 (10.0) 16 (4.4; 2.0–9.3) 1 753 342 (5.8)

Asian American 10 (5.0) NA 4 650 828 (15.4)

Other/unknown 12 (6.0) 24 (11.1; 6.8–17.7) 889 274 (2.9)

Urbanicity, n (%)§

Metro, large 151 (75.1) 297 (67.5; 60.2–74.0) 28 470 430 (76.4)

Metro, medium 40 (19.9) 87 (24.9; 18.8–32.3) 6 759 323 (18.1)

Metro, small 3 (1.5) 16 (2.7; 1.5–4.6) 1 178 974 (3.2)

Non- metro 7 (3.5) 28 (4.9; 3.0–8.0) 845 229 (2.3)

Military service, n (%)

Active duty 5 (2.5) 2 (0.5; 0.1–1.8) 127 777 (0.4)

Veteran 19 (9.5) 143 (29.2; 23.4–35.8) 1 618 861 (5.4)

*One respondent was missing age and one was missing race/ethnicity. 177 records

(88.1%) did not mention military service, which could indicate lack of service or a

lack of reporting.

†California Safety and Wellbeing Survey (CSaWS) percentages and 95% CIs are

weighted to be representative of the non- institutionalised adult population of

California. Minors are excluded from CSaWS and Asian American race is included in

‘other’. One participant was missing county.

‡Age, gender and race/ethnicity estimates were obtained from the United States

Census’ State Population by Characteristics: 2010–2019 data. Military service and

veteran information was obtained from the American Community Survey 2018 5

year estimates.

§Urbanicity was measured at the county level with the 2013 Rural–Urban

Continuum Codes. All non- metropolitan codes were collapsed into a single non-

metro category.

GVRO, gun violence restraining order.

Table 2 Circumstances of the inciting events leading to a GVRO

Cases (n=202)*

n (%)

Target of harm

Others alone 109 (54.0)

Self alone 31 (15.3)

Self and others 51 (25.2)

Other- directed targets (n=160)†

Intimate partner 47 (29.4)

Random people 37 (23.1)

Other family member 33 (20.6)

Someone at work 18 (11.2)

Someone at school 14 (8.8)

Other specific person 57 (35.6)

Threat details†

Any threat 173 (85.6)

Threatening behaviour 112 (55.4)

…with a firearm 69 (34.2)

…without a weapon 42 (20.8)

…with another weapon 13 (6.4)

Verbal threat 104 (51.5)

Mail/email/text threat 27 (13.4)

Threat posted on social media 11 (5.4)

Other 3 (1.5)

Potential mass shooting‡

Yes 58 (28.7)

No 136 (67.3)

Terrorism investigation

Yes 3 (1.5)

No 192 (95.0)

Sociopolitical or religious motivation

Yes 7 (3.5)

No 186 (92.1)

Location

Private residence 119 (58.9)

Workplace 30 (14.9)

Internet 13 (6.4)

Public place 12 (5.9)

School 7 (3.5)

Child present

Yes 34 (16.8)

No 161 (79.7)

*201 unique respondents; one person had two distinct GVROs. Percentages are

calculated with unknown (missing) values in the denominator.

†Categories are not mutually exclusive. Threat details were coded as (1) if present

and otherwise left blank (0), so we cannot distinguish between ‘no’ and ‘unknown’.

‡A potential mass shooting was defined as a threat to shoot an unspecified number

of people or at least three people other than oneself.

GVRO, gun violence restraining order.

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from

PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

4

Original research

or GVRO service, nearly one- third of respondents were arrested

on criminal charges and just under one- fourth were placed on

an involuntary psychiatric hold. Police use of force (including

compliance holds, pointing a firearm at the respondent and the

use of ‘less lethal weapons’ like bean bag rounds and tasers)

was noted in 5.0% of cases. The 1- year order after a hearing

was issued in 53.5% of cases, sought but not issued in 9.9%

of cases and not sought in 33.2% of cases. Petitioners were far

more likely to have legal representation than respondents at the

hearing for the 1- year order (67.3% vs 18.3%, respectively).

Additional process details are presented in online supplemental

etable 4.

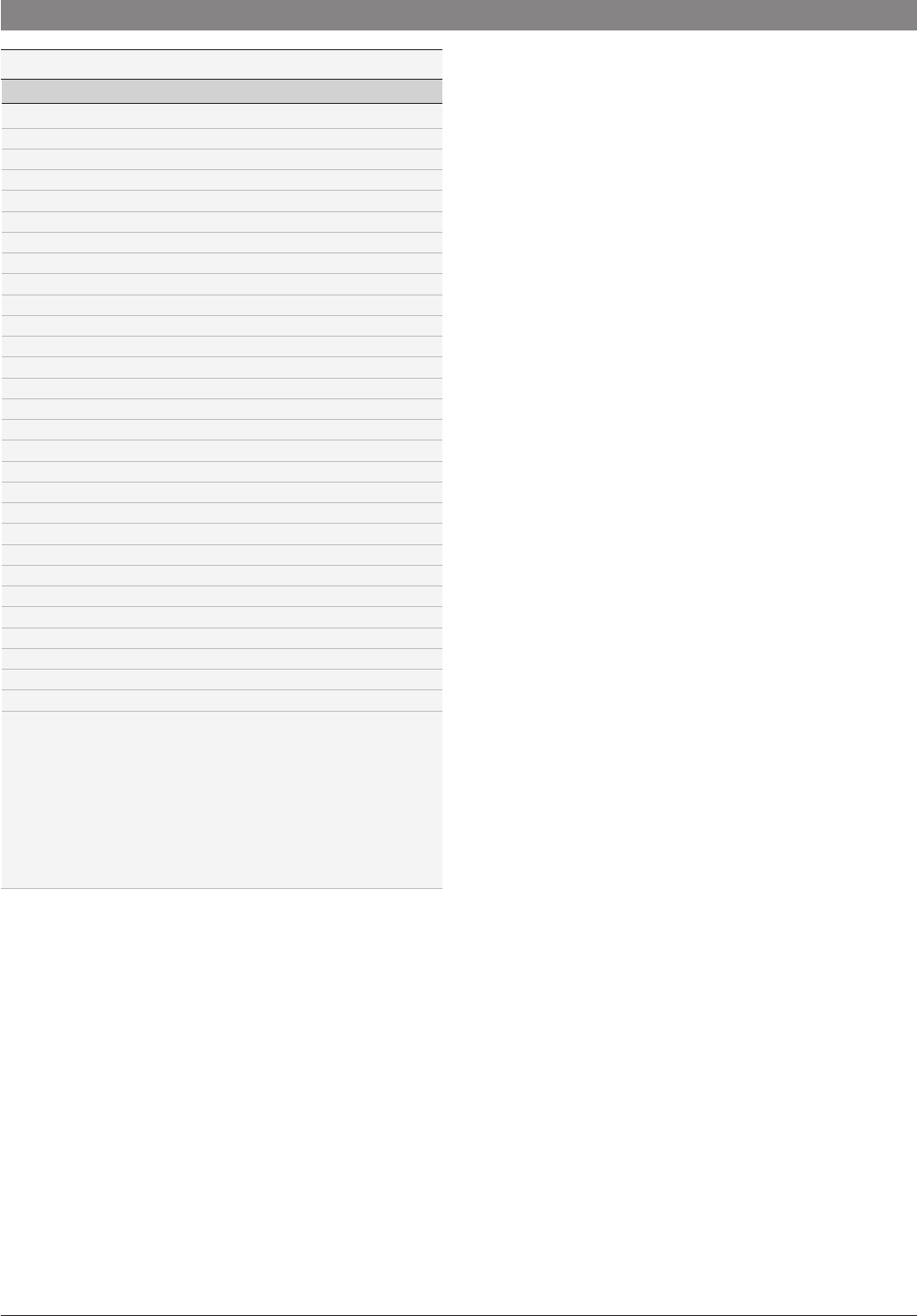

Firearm access and recovery

Based on information in the court documents, the majority

(84.2%) of respondents owned a firearm at the time of the inciting

event, and a small number had access to another’s firearm (4.5%)

or were in the 10- day waiting period after purchasing a firearm

(2.5%; table 5). Firearm removal was documented in 55.9%

of cases, with a total of 653 firearms removed. Of these cases,

firearms were primarily recovered by law enforcement (85.8%).

Table 3 Respondent risk factors

Cases (n=202)*

n (%)

Prior violence†

Self- directed violence, behaviour 11 (5.4)

Self- directed violence, threat/ideation 30 (14.9)

Intimate partner violence, behaviour 21 (10.4)

Intimate partner violence, threat/ideation 12 (5.9)

Other- directed violence (not intimate partner), behaviour 14 (6.9)

Other- directed violence (not intimate partner), threat/ideation 19 (9.4)

Harming animals 2 (1.0)

Health- related risk factors‡

Substance use 69 (34.2)

GVRO- related 54 (26.7)

Background risk 32 (15.8)

Mental illness (named diagnosis) 40 (19.8)

GVRO- related 25 (12.4)

Background risk 22 (10.9)

Undifferentiated paranoia/psychosis/hallucination 22 (10.9)

GVRO- related 20 (9.9)

Background risk 10 (5.0)

Physical health problems 18 (8.9)

GVRO- related 6 (3.0)

Background risk 14 (6.9)

Dementia/cognitive impairment 3 (1.5)

GVRO- related 2 (1.0)

Background risk 2 (1.0)

Not adhering to prescription medication regime at the time of the GVRO 8 (4.0)

Criminal legal system contact

Prior police contact with arrest/charges 43 (21.3)

Prior police contact without arrest/charges 28 (13.9)

Current restraining/protective orders 7 (3.5)

Prior restraining/protective orders 3 (1.5)

Social/structural risk factors‡

Loss/relationship problems, intimate partner 46 (22.8)

GVRO- related 42 (20.8)

Background risk 23 (11.4)

Unemployment/employment problems 24 (11.9)

GVRO- related 13 (6.4)

Background risk 13 (6.4)

Loss/relationship problems, not intimate partner 16 (7.9)

GVRO- related 8 (4.0)

Background risk 11 (5.4)

Social isolation/alienation 9 (4.5)

GVRO- related 4 (2.0)

Background risk 6 (3.0)

Housing instability 7 (3.5)

GVRO- related 4 (2.0)

Background risk 5 (2.5)

Engagement with hate groups/propaganda 6 (3.0)

GVRO- related 4 (2.0)

Background risk 3 (1.5)

*201 unique respondents; one person had two distinct GVROs. These risk factors were coded as (1) if

present and otherwise left blank (0), so we cannot distinguish between ‘no’ and ‘unknown’.

†Prior violence refers to violence that occurred before the GVRO inciting event. Violent behaviours are

actions that cause harm or could cause harm, such as cutting or hitting. Violent threats are threats that

are communicated to others (eg, verbally, in writing, in pictures). Violent ideations are thoughts about

harming others or one’s self.

‡In contrast to GVRO- related risk factors, background risk factors are not directly related to the GVRO

inciting event.

GVRO, gun violence restraining order.

Table 4 GVRO process details

Cases (n=202)*

n (%)

Petitioner relationship to respondent

Law enforcement officer 195 (96.5)

Family/household member 7 (3.5)

Source of information to petitioner†

Respondent 101 (50.0)

Family or household member 66 (32.7)

Significant other 56 (27.7)

Bystander/witness 45 (22.3)

Law enforcement (not including petitioner) 38 (18.8)

Medical personnel 24 (11.9)

Friend 25 (12.4)

Coworker 13 (6.4)

Social media 13 (6.4)

School employee 11 (5.4)

Other 6 (3.0)

Police action at contact/service†

Arrest on criminal charges 66 (32.7)

5150 (involuntary psychiatric hold) 46 (22.8)

Transport to hospital 45 (22.3)

Use of force 10 (5.0)

Psychiatric evaluation (on site) 5 (2.5)

Order after a hearing

Issued 108 (53.5)

Sought but not issued 20 (9.9)

Not sought 67 (33.2)

Legal representation at hearing (among those with an

order after a hearing form, n=104‡)

Petitioner only 55 (52.9)

Respondent only 4 (3.8)

Petitioner and respondent 15 (14.4)

None 28 (26.9)

*201 unique respondents; one person had two distinct GVROs. Percentages are

calculated with unknown (missing) values in the denominator.

†These were coded as (1) if present and otherwise left blank (0), so we cannot

distinguish between ‘no’ and ‘unknown’.

‡The order after a hearing form was missing for four cases in which we believe the

order after a hearing was granted (based on court minutes and other forms in the

file) and for all cases in which it was sought but not granted.

GVRO, gun violence restraining order.

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from

PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

5

Original research

While most cases with a firearm removal included handguns, a

substantial number (29.2%) included assault- type weapons (see

online supplemental emethods for identification guidelines).

Finally, case records indicated that at least one firearm owned

by or accessible to the respondent was not recovered in 11.9%

of cases.

Respondent mortality

LexisNexis was able to match 379 (91.8%) of the 413 total

GVROs respondents, 2016–2018. Among these, seven (1.8%)

died after being issued a GVRO. All were white men over 45

years old (mean=62.7 years). One died by firearm suicide;

however, the GVRO was issued in response to the self- inflicted

gunshot wound that ultimately resulted in his death. Three

deaths were from unintentional injuries (drowning, overdose

and motor vehicle crash) and the others were from unrelated

medical conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we elucidated precipitating circumstances for

GVROs, process details and respondent outcomes using court

records and mortality data for GVRO respondents in California,

2016–2018. This is the first detailed description of GVRO cases

in the state and both complements and extends our previous

study on uptake of the law.

7

These findings provide insight into

GVRO use, respondent mortality and areas for improvement in

implementation.

We found that most GVROs involved risk of harm to others,

which was present in nearly 80% of cases—about two times the

percentage of cases involving risk of self- directed harm. This

differs from the experience of other states and counties that

have reported details of the use of ERPO- type laws. In Oregon,

Connecticut and King County, Washington, the proportion of

cases involving self- directed harm was higher than the propor-

tion involving other- directed harm, sometimes substantially

so.

5 13 14

Washington State, Colorado and Broward County,

Florida had more other- directed than self- directed harm cases,

but the difference between the two proportions was smaller

(7%–19%) than in California (nearly 40%).

15–17

This unique

pattern of use in California may reflect a lower prevalence of

suicide in the underlying population: the rate of firearm suicide

in California is among the lowest in the country (although this

is also true of Connecticut).

1

Additionally, the ratio of firearm

homicide to firearm suicide in California is almost 1:1,

18

whereas

nationwide, it is closer to 1:2.

19

California also has more strin-

gent firearm regulations than other states, including prohibitions

following an involuntary mental health hold, which may reduce

the need for GVROs in cases involving suicidality. Finally, differ-

ences could stem from variation in the type of cases for which

petitioners believe GVROs are best suited.

The most common violence- related risk factor identified in

the court records was substance use, present in over one- third

of cases. This proportion is similar to that found in Broward

County, Florida, but lower than that reported in Washington and

Oregon (46%–47%).

13 15 17

Substance use is a well- established

risk factor for violent and suicidal behaviour.

20–22

Other common

risk factors present in the case files included mental illness (a risk

factor primarily for suicide), prior arrest, and relationship loss/

problems, each present in about 20% of cases. Many of these risk

factors suggest that the respondent may have had contact with

healthcare or social services that could have provided help prior

to the inciting event. It would be prudent to consider how these

early contacts could be used to help alleviate issues before they

escalate to the point where a GVRO is needed, such as through

identification of substance use problems and timely referral to

affordable treatment programmes, counselling and clinician-

initiated conversations about firearm access with patients at high

risk of violence.

23 24

Our findings regarding the GVRO process raised several

potential concerns. We found that nearly one in three respon-

dents were arrested on criminal charges at the time of police

contact for the inciting event or during GVRO service. This

is much greater than the 17% of respondents arrested in

Connecticut and 8% in Marion County, Indiana.

4 5

This may

reflect the higher proportion of cases in California that are for

threatened other- directed harm, which can involve criminal

offences like threats, assault or domestic battery. Key informants

in California previously suggested arrests and GVROs can some-

times be complementary, such as when individuals at risk for

violence would otherwise have access to firearms after posting

bail.

9

However, there may be cause for concern if GVROs, which

Table 5 Firearm details

Among all respondents (n=202)*… n (%)

Firearm access/ownership†

Access, owner 170 (84.2)

Access, not owner 9 (4.5)

Purchased, in waiting period 5 (2.5)

Intends to purchase 2 (1.0)

No known access 12 (5.9)

Work- related firearm access‡ 8 (4.0)

Any firearm removal pursuant to GVRO‡ 113 (55.9)

Any known firearms not recovered‡ 24 (11.9)

Among respondents with removals (n=113)…

Total firearms removed 653

Median (25th–75th pctl) no. firearms removed/person 2 (1, 4)

Undocumented firearms recovered§

Yes 27 (23.9)

No 78 (69.0)

Cases with additional firearms not recovered‡ 13 (11.5)

Type of firearms removed

Any handguns

Yes 96 (85.0)

No 13 (11.5)

Any long guns

Yes 53 (46.9)

No 54 (47.8)

Any assault- type weapons

Yes 33 (29.2)

No 73 (64.6)

Mechanism of firearm recovery

Law enforcement 97 (85.8)

Licensed firearm dealer 9 (8.0)

*201 unique respondents; one person had two distinct GVROs. Percentages are

calculated with unknown (missing) values in the denominator.

†Categories are mutually exclusive. Individuals were classified according to the

most proximal ownership/access category that applied.

‡These were coded as (1) if present and otherwise left blank (0), so we can’t

distinguish between ‘no’ and ‘unknown’.

§Undocumented firearms are those that the State did not know the respondent

possessed (based on firearm transaction records).

¶

GVRO, gun violence restraining order.

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from

PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

6

Original research

are civil mechanisms, are leading to arrests. If they are used puni-

tively without complementary social service resources, family

and friends may be discouraged from alerting law enforcement

to potentially dangerous situations out of fear of enmeshing the

person at risk in the criminal legal system.

We also found that the 1- year order after a hearing was not

sought in one- third of cases. When it was sought, the 1- year

order was issued 84% of the time. In all, just over 50% of cases

resulted in an order after a hearing (this would be lower if we

had received court records for the emergency orders that courts

were unable to locate). In contrast, about 80% of cases in Wash-

ington State and Colorado and 87% in Broward County, Florida

resulted in long- term orders following a hearing.

15–17

Reasons

for this difference should be further explored but suggest varia-

tion in use or case circumstances, with California cases perhaps

reflecting shorter- term, acute crises.

Our findings regarding orders after a hearing raised another

potential concern: of respondents with a hearing, only 18.3%

had legal representation. Key informants previously noted that

this could perpetuate class- based disparities in the legal system,

10

with wealthier respondents more often avoiding the order after a

hearing than others. We do not have data on respondent income,

but a slightly higher proportion of cases in which the respon-

dent had a lawyer resulted in the order after a hearing being

denied when it was sought (18.5% vs 14.9%). Given the small

number of respondents with a lawyer, this can only be taken as

suggestive.

An additional indication that implementation can be improved

is that firearms known to law enforcement were not recovered

in 12% of cases—two times the 5% reported in King County,

Washington.

14

Firearms may go unrecovered for many reasons,

including being sold, stolen, lost or hidden and due to lack of

officer follow- up when they are stored outside of the respon-

dent’s home. This undermines the purpose of the order and pres-

ents a clear safety concern; we suggest law enforcement agencies

create and/or review strategies to locate and recover outstanding

firearms.

Our findings also highlight ways in which GVROs may have

prevented suicide among respondents, 40.6% of whom were

issued a GVRO for reasons including a threat of self- harm. One

responded died by suicide using a firearm, but the injury was

inflicted during the inciting event that resulted in the GVRO,

before the order had been issued. No other respondents in the

first 3 years of implementation died by suicide post- GVRO,

using firearms or other means. Around 3% of respondents died

by suicide after being issued a risk warrant (another risk- based

temporary firearm removal law) in Connecticut and Marion

County, Indiana, yet the laws in those states were found to

be effective at preventing firearm suicide.

4 5

These studies are

not directly comparable to ours, though, as they had longer

follow- up periods. We had a small number of respondents and

a short period of follow- up and cannot infer causation between

the order and subsequent lack of suicide, but these findings are

promising nevertheless.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. We did not receive court

files for all GVRO cases issued during the study period. Cases

consisting only of emergency orders were under- represented in

our data and our findings may not generalise to them. However,

we received nearly all files with an order after a hearing, which

likely represent the cases with the most enduring need for

intervention.

Additionally, we were limited by the information included

in the case files. Much of the contextual information, such as

respondent risk factors and the circumstances precipitating the

order, came from narratives included in the petition. Petitioners

used their judgement about what details were pertinent and

drew on different sources of information depending on who

they contacted.

Finally, we were limited to evaluating mortality only among

respondents, who threatened self- harm in about 40% of cases.

The case files did not include the necessary individual- level

information needed to link mortality data to other individuals

threatened by respondents, so these mortality outcomes remain

uncertain. In the future, GVRO researchers will need to consider

how best to evaluate outcomes among those who primarily make

threats against others.

CONCLUSIONS

GVROs in California, 2016–2018, were used primarily to

prevent other- directed harm, including mass shootings. While

our findings raised some concerns, we also found evidence

suggestive of success: in particular, no suicides occurred post-

GVRO. Future research should examine cases in more recent

years, as uptake increased dramatically in 2019.

7

It should also

examine differences by race/ethnicity to identify potential indica-

tors of inequitable use.

8

Finally, given that GVROs are primarily

being used to prevent assaultive violence in California, there is a

pressing need for additional effectiveness evaluations examining

this type of firearm violence.

25

Acknowledgements We thank Albert Hu and Annie Adachi for their work in

requesting and abstracting GVRO court case files.

Contributors GJW conceived of the study. VAP, RP, JPS, ET, NK- W, CEK and

GJW drafted the codebook for data abstraction. VAP, RP, JPS and ET oversaw data

abstraction and acquisition. VAP analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All

authors made substantial contributions to interpreting the data and revising the

manuscript. VAP is responsible for the overall content of the study as guarantor.

Funding This work was supported by the Fund for a Safer Future (NVF FFSF UC

Davis GA004701) and the California Firearm Violence Research Center (no award

number).

Disclaimer The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study;

collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review,

or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in

the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication Not applicable.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the University of California, Davis

Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement No data are available. No data are publicly

available.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s).

It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not

have been peer- reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are

solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all

liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content.

Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the

accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local

regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and

is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and

adaptation or otherwise.

Open access This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which

permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially,

and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from

PearVA, etal. Inj Prev 2022;0:1–7. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544

7

Original research

properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use

is non- commercial. See:http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

ORCID iDs

Veronica APear http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2462-3785

Julia PSchleimer http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6439-7586

NicoleKravitz- Wirtz http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7827-0196

Christopher EKnoepke http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3521-7157

REFERENCES

1 Web- Based injury statistics query and reporting system. National center for injury

prevention and control, centers for disease control and prevention. 2005, 2020.

Available: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars [Accessed 26 Aug 2021].

2 Mass attacks in public spaces, 2019. United States secret service, National threat

assessment center, us department of homeland security, 2020. Available: www.

secretservice.gov/data/press/reports/USSS_FY2019_MAPS.pdf

3 Cal. Penal code §18100- 18205.

4 Swanson JW, Easter MM, Alanis- Hirsch K, etal. Criminal justice and suicide

outcomes with Indiana’s Risk- Based gun seizure law. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law

2019;47:188–97.

5 Swanson JW, Norko MA, Lin H. Implementation and effectiveness of Connecticut’s

risk- based gun removal law: Does it prevent suicides? Law Contemp Probl

2017;80:179–208.

6 Wintemute GJ, Pear VA, Schleimer JP, etal. Extreme risk protection orders intended to

prevent mass shootings: a case series. Ann Intern Med 2019;171:655–8.

7 Pallin R, Schleimer JP, Pear VA, etal. Assessment of extreme risk protection order use

in California from 2016 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e207735.

8 Swanson JW. The color of risk protection orders: gun violence, gun laws, and racial

justice. Inj Epidemiol 2020;7:46.

9 Pallin R, Tomsich E, Schleimer JP, etal. Understanding the circumstances and

stakeholder perceptions of gun violence restraining order use in California: a

qualitative study. Criminol Public Policy 2021;20:755–73. doi:10.1111/1745-

9133.12560

10 Pear VA, Schleimer JP, Tomsich E, etal. Implementation and perceived effectiveness

of gun violence restraining orders in California: a qualitative evaluation. PLoS One

2021;16:e0258547.

11 Fact sheet: Biden- Harris adminsitration announces initial actions to address the gun

violence public health epidemic. the white house, 2021. Available: www.whitehouse.

gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/04/07/fact-sheet-biden-harris-

administration-announces-initial-actions-to-address-the-gun-violence-public-health-

epidemic/ [Accessed 01 May 2021].

12 Kravitz- Wirtz N, Pallin R, Miller M, etal. Firearm ownership and acquisition in

California: findings from the 2018 California safety and well- being survey. Inj Prev

2020;26:516–23.

13 Zeoli AM, Paruk J, Branas CC, etal. Use of extreme risk protection orders to reduce

gun violence in Oregon. Criminol Public Policy 2021;20:243–61.

14 Frattaroli S, Omaki E, Molocznik A, etal. Extreme risk protection orders in King

County, Washington: the epidemiology of dangerous behaviors and an intervention

response. Inj Epidemiol 2020;7:44.

15 Rowhani- Rahbar A, Bellenger MA, Gibb L, etal. Extreme risk protection orders in

Washington : A statewide descriptive study. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:342–9.

16 Barnard LM, McCarthy M, Knoepke CE, etal. Colorado’s first year of extreme risk

protection orders. Inj Epidemiol 2021;8:59.

17 Drane K. Preventing the next Parkland: A case study of the use and implementation

of Florida’s extreme risk law in Broward County. Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun

Violence, 2020. Available: https://lawcenter.giffords.org/preventing-the-next-parkland-

a-case-study-of-broward-countys-use-and-implementation-of-floridas-extreme-risk-

law/

18 Pear VA, Castillo- Carniglia A, Kagawa RMC, etal. Firearm mortality in California,

2000- 2015: the epidemiologic importance of within- state variation. Ann Epidemiol

2018;28:309–15.

19 Wintemute GJ. The epidemiology of firearm violence in the twenty- first century United

States. Annu Rev Public Health 2015;36:5–19.

20 Boles SM, Miotto K. Substance abuse and violence: a review of the literature.

Aggression and Violent Behavior 2003;8:155–74.

21 Poorolajal J, Haghtalab T, Farhadi M, etal. Substance use disorder and risk of

suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide death: a meta- analysis. J Public Health

2016;38:e282–91.

22 Lynch FL, Peterson EL, Lu CY, etal. Substance use disorders and risk of suicide in a

general US population: a case control study. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2020;15:14.

23 Wintemute GJ, Betz ME, Ranney ML. Yes, you can: physicians, patients, and firearms.

Ann Intern Med 2016;165:205–13.

24 Pallin R, Spitzer SA, Ranney ML, etal. Preventing firearm- related death and injury.

Ann Intern Med 2019;170:ITC81–96.

25 Pear VA, Wintemute GJ, Jewell NP, etal. Firearm violence following the

implementation of California’s gun violence restraining order law. JAMA Netw Open

2022;5:e224216.

on September 6, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/Inj Prev: first published as 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544 on 2 June 2022. Downloaded from