Sponsored by:

In cooperation with:

American Association of State Highway

and Transportation Ocials

National Cooperative Highway

Research Program

August 2012

International Technology

Scanning Program

Transportation Risk Management:

International Practices for Program

Development and Project Delivery

NOTICE

The Federal Highway Administration provides high-

quality information to serve Government, industry,

and the public in a manner that promotes public

understanding. Standards and policies are used to

ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility,

and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically

reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and

processes to ensure continuous quality improvement.

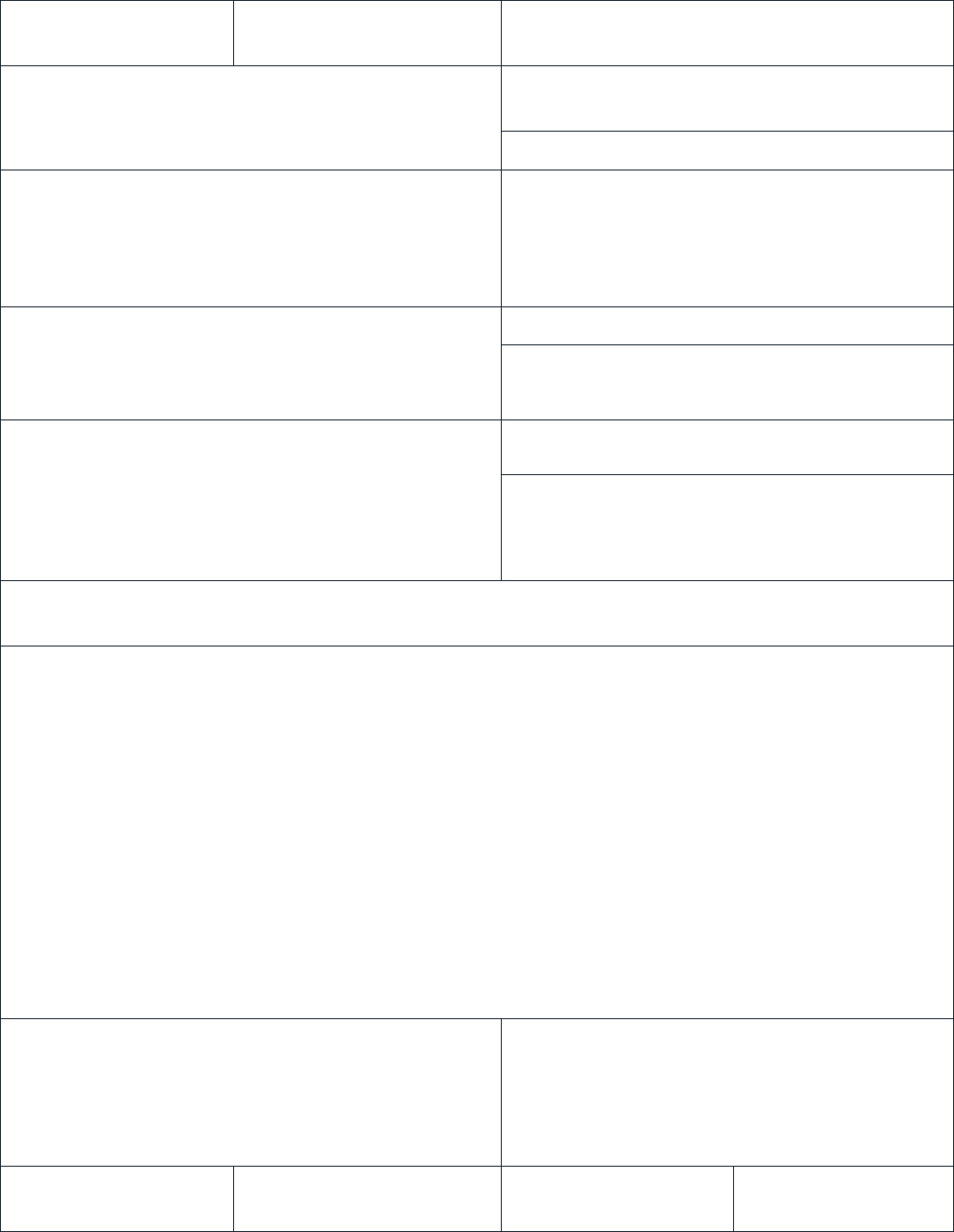

1. Report No.

FHWA-PL-12-029

2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No.

4. Title and Subtitle

Transportation Risk Management: International

Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery

5. Report Date

August 2012

6. Performing Organization Code

7. Author(s)

Joyce A. Curtis, Joseph S. Dailey, Daniel D’Angelo,

Steven D. DeWitt, Michael J. Graf, Timothy A. Henkel,

Dr. John B. Miller, Dr. John C. Milton, Dr. Keith R.

Molenaar, Darrell M. Richardson, Robert E. Rocco

8. Performing Organization Report No.

9. Performing Organization Name and Address

American Trade Initiatives

3 Faireld Court

Stafford, VA 22554-1716

10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS)

11. Contract or Grant No.

DTFH61-10-C-00027

12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address

Ofce of International Programs

Federal Highway Administration

U.S. Department of Transportation

American Association of State Highway and

Transportation Ofcials

13. Type of Report and Period Covered

14. Sponsoring Agency Code

15. Supplementary Notes

FHWA COTR: Hana Maier, Ofce of International Programs

16. Abstract

Studies show that U.S. highway agencies have only recently begun to develop formal risk management policies

and procedures at the enterprise, program, and project levels. The Federal Highway Administration, American

Association of State Highway and Transportation Ofcials, and National Cooperative Highway Research

Program sponsored a scanning study of Australia and Europe to document risk management policies, practices,

and strategies for potential application in the United States.

The scan team found that the leading international transportation agencies have mature risk management

practices. The team observed that risk management supports strategic organizational alignment, helps

apportion risks to the parties best able to manage them, and facilitates good decisionmaking and accountability

at all levels of the organizations.

Team recommendations for U.S. implementation include developing executive-level support for risk

management at transportation agencies, dening risk management leadership and organizational

responsibilities, and using risk management to make the business case for transportation and build trust

with transportation stakeholders.

17. Key Words

Asset management, enterprise, performance

management, program development, project delivery,

risk management

18. Distribution Statement

No restrictions. This document is available to the public

from the: Ofce of International Programs, FHWA-HPIP,

Room 3325, U.S. Department of Transportation,

Washington, DC 20590

[email protected], www.international.fhwa.dot.gov

19. Security Classify. (of this report)

Unclassied

20. Security Classify. (of this page)

Unclassied

21. No. of Pages

80

22. Price

Free

Form DOT F 1700.7 (8-72) Reproduction of completed page authorized

Technical Report Documentation Page

Transportation Risk Management:

International Practices for Program

Development and Project Delivery

August 2012

PREPARED BY THE INTERNATIONAL SCANNING STUDY TEAM:

Joyce A. Curtis (Cochair)

FHWA

Daniel D’Angelo (Cochair)

New York State DOT

Dr. Keith R. Molenaar

(Report Facilitator)

University of Colorado

Joseph S. Dailey

FHWA

Steven D. DeWitt

North Carolina Turnpike Authority

Michael J. Graf

FHWA

Timothy A. Henkel

Minnesota DOT

Dr. John B. Miller

Barchan Foundation, Inc.

Dr. John C. Milton

Washington State DOT

Darrell M. Richardson

Georgia DOT

Robert E. Rocco

AECOM Transportation

FOR

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Ocials

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

iv International Technology Scanning Program

International Technology

Scanning Program

T

he International Technology Scanning

Program, sponsored by the Federal Highway

Administration (FHWA), the American

Association of State Highway and

Transportation Ocials (AASHTO), and the National

Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP),

evaluates innovative foreign technologies and

practices that could significantly benefit U.S. high-

way transportation systems. This approach allows

for advanced technology to be adapted and put into

practice much more eciently without spending

scarce research funds to re-create advances already

developed by other countries.

FHWA and AASHTO, with recommendations from

NCHRP, jointly determine priority topics for teams

of U.S. experts to study. Teams in the specific areas

being investigated are formed and sent to countries

where significant advances and innovations have

been made in technology, management practices,

organizational structure, program delivery, and

financing. Scan teams usually include representa-

tives from FHWA, State departments of transporta-

tion, local governments, transportation trade and

research groups, the private sector, and academia.

After a scan is completed, team members evaluate

findings and develop comprehensive reports, includ-

ing recommendations for further research and pilot

projects to verify the value of adapting innovations

for U.S. use. Scan reports, as well as the results of

pilot programs and research, are circulated through-

out the country to State and local transportation

ocials and the private sector. Since 1990, more

than 85 international scans have been organized on

topics such as pavements, bridge construction and

maintenance, contracting, intermodal transport,

organizational management, winter road mainte-

nance, safety, intelligent transportation systems,

planning, and policy.

The International Technology Scanning Program has

resulted in significant improvements and savings in

road program technologies and practices through-

out the United States. In some cases, scan studies

have facilitated joint research and technology-

sharing projects with international counterparts,

further conserving resources and advancing the

state of the art. Scan studies have also exposed

transportation professionals to remarkable advance-

ments and inspired implementation of hundreds of

innovations. The result: large savings of research

dollars and time, as well as significant improvements

in the Nation’s transportation system.

Scan reports can be obtained through FHWA

free of charge by e-mailing international@

dot.gov. Scan reports are also available

electronically and can be accessed on the FHWA

Oce of International Programs Web site at

www.international.fhwa.dot.gov.

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery v

International Technology Scan Reports

International Technology Scanning Program: Bringing Global Innovations to U.S. Highways

» Safety

Infrastructure Countermeasures to Mitigate

Motorcyclist Crashes in Europe (2012)

Assuring Bridge Safety and Serviceability in Europe

(2010)

Pedestrian and Bicyclist Safety and Mobility

in Europe (2010)

Improving Safety and Mobility for Older Road

Users in Australia and Japan (2008)

Safety Applications of Intelligent Transportation

Systems in Europe and Japan (2006)

Trac Incident Response Practices in Europe (2006)

Underground Transportation Systems in Europe:

Safety, Operations, and Emergency Response

(2006)

Roadway Human Factors and Behavioral Safety

in Europe (2005)

Trac Safety Information Systems in Europe

and Australia (2004)

Signalized Intersection Safety in Europe (2003)

Managing and Organizing Comprehensive Highway

Safety in Europe (2003)

European Road Lighting Technologies (2001)

Commercial Vehicle Safety, Technology, and Practice

in Europe (2000)

Methods and Procedures to Reduce Motorist Delays

in European Work Zones (2000)

Innovative Trac Control Technology and Practice

in Europe (1999)

Road Safety Audits—Final Report and Case Studies

(1997)

Speed Management and Enforcement Technology:

Europe and Australia (1996)

Safety Management Practices in Japan, Australia,

and New Zealand (1995)

Pedestrian and Bicycle Safety in England, Germany,

and the Netherlands (1994)

» Planning and Environment

Reducing Congestion and Funding Transportation

Using Road Pricing In Europe and Singapore (2010)

Linking Transportation Performance and

Accountability (2010)

Streamlining and Integrating Right-of-Way and

Utility Processes With Planning, Environmental, and

Design Processes in Australia and Canada (2009)

Active Travel Management: The Next Step in

Congestion Management (2007)

Managing Travel Demand: Applying European

Perspectives to U.S. Practice (2006)

Transportation Asset Management in Australia,

Canada, England, and New Zealand (2005)

Transportation Performance Measures in Australia,

Canada, Japan, and New Zealand (2004)

European Right-of-Way and Utilities Best Practices

(2002)

Geometric Design Practices for European Roads

(2002)

Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Across European

Highways (2002)

vi International Technology Scan Reports

Sustainable Transportation Practices in Europe

(2001)

Recycled Materials in European Highway

Environments (1999)

European Intermodal Programs: Planning, Policy,

and Technology (1999)

National Travel Surveys (1994)

» Policy and Information

Transportation Risk Management: International

Practices for Program Development and Project

Delivery (2012)

Understanding the Policy and Program Structure

of National and International Freight Corridor

Programs in the European Union (2012)

Outdoor Advertising Control Practices in Australia,

Europe, and Japan (2011)

Transportation Research Program Administration

in Europe and Asia (2009)

Practices in Transportation Workforce Development

(2003)

Intelligent Transportation Systems and Winter

Operations in Japan (2003)

Emerging Models for Delivering Transportation

Programs and Services (1999)

National Travel Surveys (1994)

Acquiring Highway Transportation Information

From Abroad (1994)

International Guide to Highway Transportation

Information (1994)

International Contract Administration Techniques

for Quality Enhancement (1994)

European Intermodal Programs: Planning, Policy, and

Technology (1994)

» Operations

Freight Mobility and Intermodal Connectivity in

China (2008)

Commercial Motor Vehicle Size and Weight

Enforcement in Europe (2007)

Active Travel Management: The Next Step in

Congestion Management (2007)

Managing Travel Demand: Applying European

Perspectives to U.S. Practice (2006)

Trac Incident Response Practices in Europe (2006)

Underground Transportation Systems in Europe:

Safety, Operations, and Emergency Response

(2006)

Superior Materials, Advanced Test Methods, and

Specifications in Europe (2004)

Freight Transportation: The Latin American Market

(2003)

Meeting 21st Century Challenges of System

Performance Through Better Operations (2003)

Traveler Information Systems in Europe (2003)

Freight Transportation: The European Market (2002)

European Road Lighting Technologies (2001)

Methods and Procedures to Reduce Motorist Delays

in European Work Zones (2000)

Innovative Trac Control Technology and Practice in

Europe (1999)

European Winter Service Technology (1998)

Trac Management and Traveler Information

Systems (1997)

European Trac Monitoring (1997)

Highway/Commercial Vehicle Interaction (1996)

Winter Maintenance Technology and Practices—

Learning from Abroad (1995)

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery vii

Advanced Transportation Technology (1994)

Snowbreak Forest Book—Highway Snowstorm

Countermeasure Manual (1990)

» Infrastructure—General

Infrastructure Countermeasures to Mitigate

Motorcyclist Crashes in Europe (2012)

Freeway Geometric Design for Active Trac

Management in Europe (2011)

Public-Private Partnerships for Highway

Infrastructure: Capitalizing on International

Experience (2009)

Audit Stewardship and Oversight of Large and

Innovatively Funded Projects in Europe (2006)

Construction Management Practices in Canada and

Europe (2005)

European Practices in Transportation Workforce

Development (2003)

Contract Administration: Technology and Practice in

Europe (2002)

European Road Lighting Technologies (2001)

Geometric Design Practices for European Roads

(2001)

Geotechnical Engineering Practices in Canada and

Europe (1999)

Geotechnology—Soil Nailing (1993)

» Infrastructure—Pavements

Managing Pavements and Monitoring Performance:

Best Practices in Australia, Europe, and New Zealand

(2012)

Warm-Mix Asphalt: European Practice (2008)

Long-Life Concrete Pavements in Europe and

Canada (2007)

Quiet Pavement Systems in Europe (2005)

Pavement Preservation Technology in France,

South Africa, and Australia (2003)

Recycled Materials in European Highway

Environments (1999)

South African Pavement and Other Highway

Technologies and Practices (1997)

Highway/Commercial Vehicle Interaction (1996)

European Concrete Highways (1992)

European Asphalt Technology (1990)

» Infrastructure—Bridges

Assuring Bridge Safety and Serviceability in Europe

(2010)

Bridge Evaluation Quality Assurance in Europe

(2008)

Prefabricated Bridge Elements and Systems in Japan

and Europe (2005)

Bridge Preservation and Maintenance in Europe and

South Africa (2005)

Performance of Concrete Segmental and Cable-

Stayed Bridges in Europe (2001)

Steel Bridge Fabrication Technologies in Europe and

Japan (2001)

European Practices for Bridge Scour and Stream

Instability Countermeasures (1999)

Advanced Composites in Bridges in Europe and

Japan (1997)

Asian Bridge Structures (1997)

Bridge Maintenance Coatings (1997)

Northumberland Strait Crossing Project (1996)

European Bridge Structures (1995)

All publications are available on the Internet at www.international.fhwa.dot.gov.

viii

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery ix

Contents

Executive Summary ......................... 1

Background ............................... 1

What is Risk Management? .................. 1

Purpose and Scope ........................ 2

Observations and Key Findings .............. 3

Benefits and Challenges of Formal Risk

Management .............................. 3

Benefits ................................. 3

Challenges .............................. 3

Recommendations ......................... 3

Implementation ............................ 4

Reader’s Guide to the Report ................ 5

Chapter 1: Introduction ...................... 7

Background and Purpose ................... 7

Methodology .............................. 7

Chapter 2: Common Definitions, Strategies, and

Tools for Risk Management ...................11

Introduction ...............................11

Risk Management Definitions ................11

Risk Management Process.................. 12

Structures for Successful Risk Management ... 13

Risk Workshops ........................... 13

Risk Registers ............................ 14

Risk Quantification ........................ 19

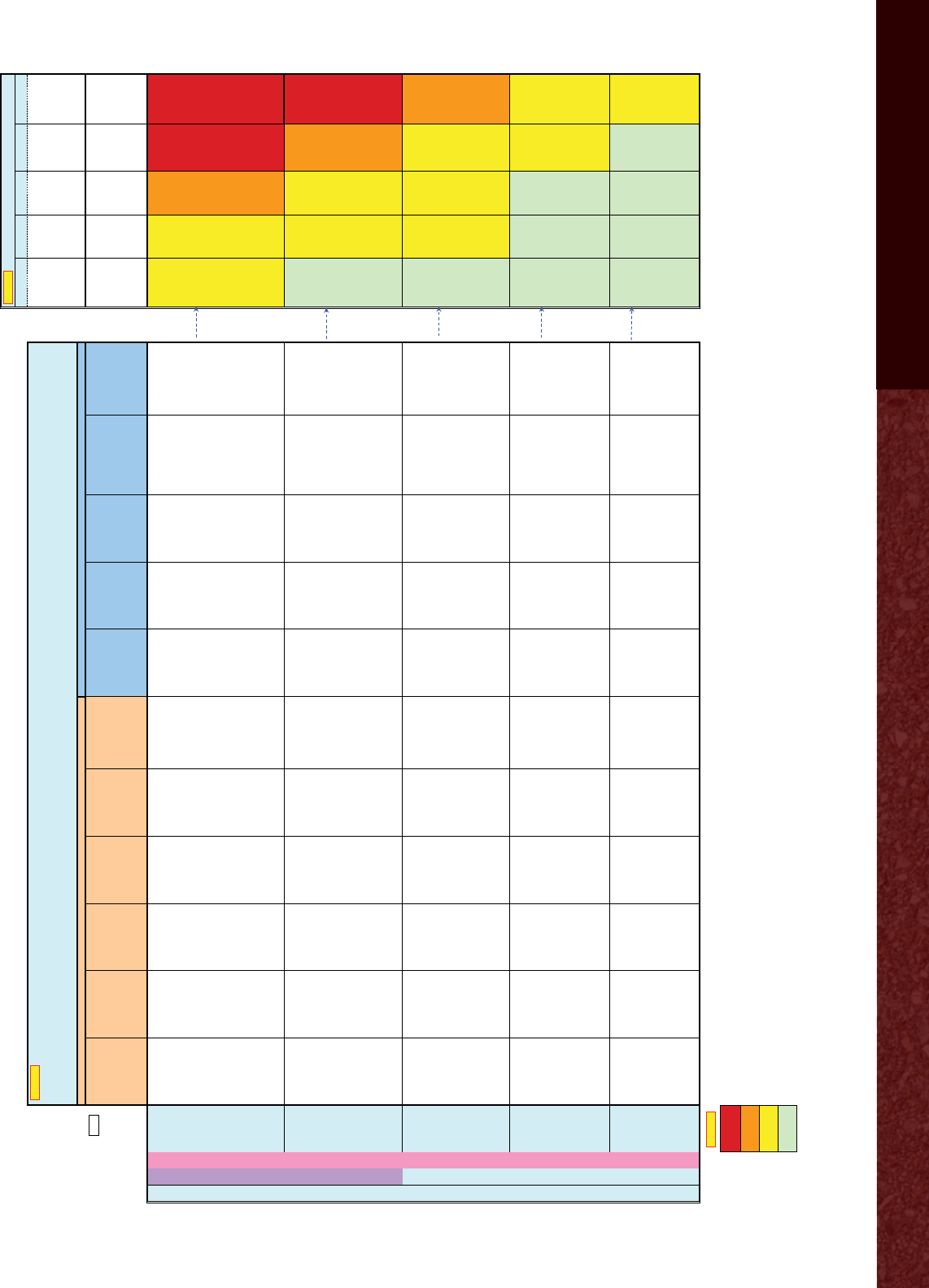

Heat Maps ............................... 19

Use of Risk Communication Strategies to

Improve Decisionmaking .................. 22

Risk Management Plan ..................... 22

Conclusion ............................... 23

Chapter 3: Agency Risk Management ......... 25

Introduction .............................. 25

Assigning Risk Management Roles,

Responsibilities, and Authority .............. 25

Relationship of Risk Management to Strategic

Objectives ............................... 26

Common Agency Strategic Objectives ..... 26

Common Agency Risks .................. 26

Development of an Explicit Risk

Management Structure ................... 26

Risk Management Policy ................... 28

Transport and Main Roads, Queensland,

Australia ...............................29

VicRoads, Victoria, Australia ..............30

Highways Agency, England ............... 31

Alignment of Risk Management Throughout

the Organization .......................... 31

Use of Risk Analysis to Examine Policies,

Processes, and Standards .................. 33

Achievement of a Risk Management Culture ..34

Conclusion ...............................34

Chapter 4: Program Risk Management ........ 35

Introduction .............................. 35

Program and Portfolio Risk ................. 35

Use of Risk Analysis for Asset

Management .............................36

Use of Risk Analysis for Operations

Management ............................. 38

Risk Management at the Division, Branch, or

Functional Unit Levels .....................38

Risk Management on Major Programs .......38

Conclusion .............................. 40

Chapter 5: Project Risk Management ......... 41

Introduction .............................. 41

Risk Management in Project Management .... 41

Project Cost and Schedule Risk Analysis .....42

Selection of Appropriate Project Risk

Allocation Methods........................43

Conclusion ...............................45

Chapter 6: Recommendations and

Implementation ............................ 47

Recommendations ........................ 47

Develop Executive Support for Risk

Management ........................... 47

Define Risk Management Leadership and

Organization ............................ 47

Formalize Risk Management

Approaches ............................47

Use Risk Management to Examine Policies,

Processes, and Standards ................ 47

Embed Risk Management in Business

Practices ...............................48

Identify Risk Owners and Levels ........... 48

Allocate Risks Appropriately ..............48

Use Risk Management to Make the Business

Case for Transportation ..................48

Employ Sophisticated Risk Tools but

Communicate Results Simply .............48

Implementation and Future Research ........48

Communication and Marketing ............50

Research ...............................50

Training ................................ 51

Governance ............................ 51

x Contents

Appendix A. Scan Team Members ............ 53

Appendix B. Amplifying Questions ........... 57

Appendix C. Bibliography and Recommended

Readings .................................. 61

Appendix D. Risk Management Process Stages

and Terminology Comparison ................62

Appendix E. Host Country Representatives ....64

Tables

Table 1. Risk management definitions

(from ISO 31000)

..............................

11

Table 2. Risk management scan implementation.

.....

49

Figures

Figure 1. Relationship of risk management to

transportation agency management.

...............

1

Figure 2. Levels of enterprise risk management

(agency, program, and project).

...................

2

Figure 3. U.S. scan team.

........................

8

Figure 4. Cyclical nature of the risk management process

(adapted from PMI and ISO 31000).

................

12

Figure 5. Generic risk workshop agenda and

attendees.

..................................

13

Figure 6. Transport Scotland’s risk workshop.

.......

15

Figure 7. Aligned risk management approach

(Transport and Main Roads, Australia).

.............

15

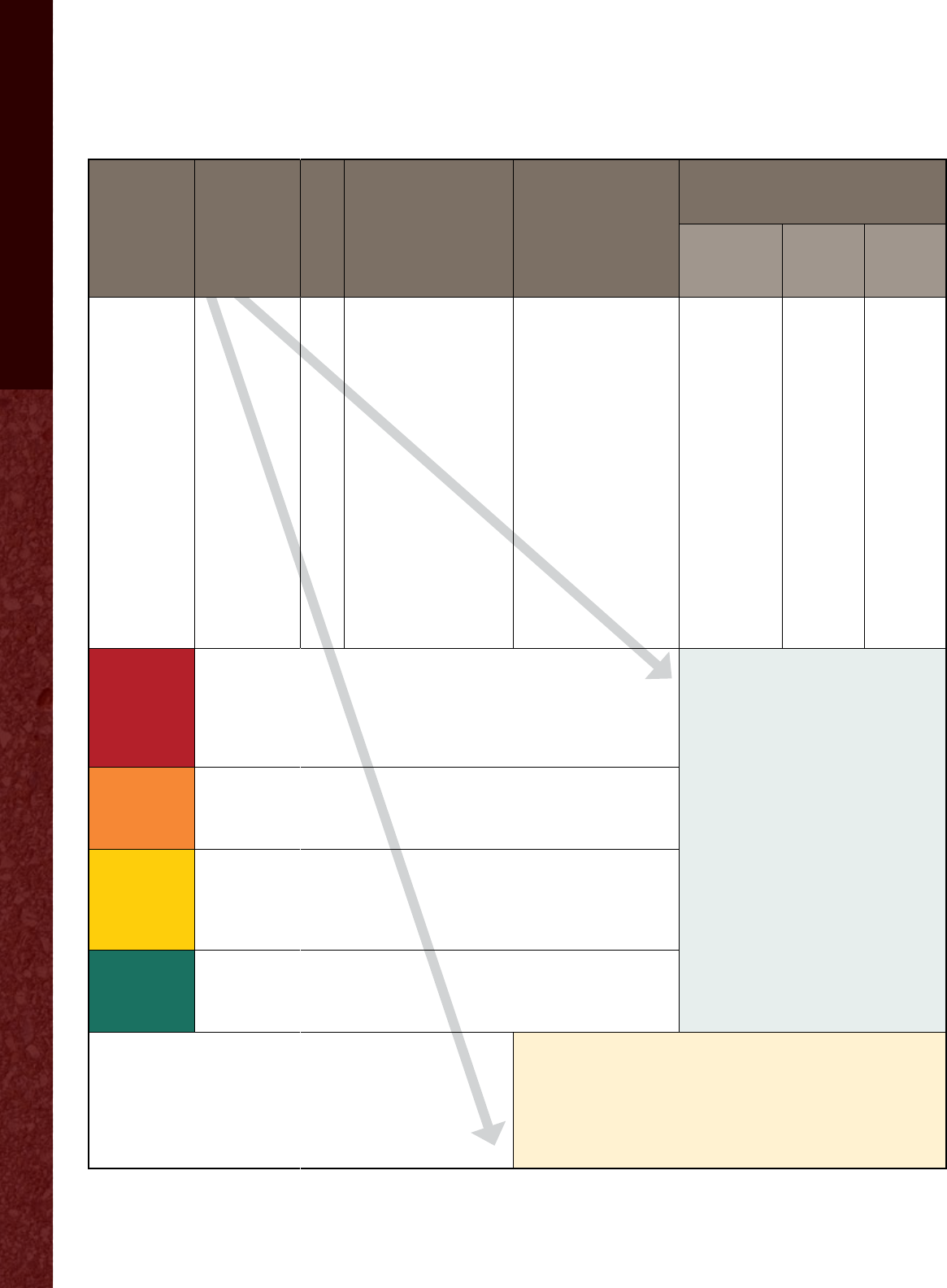

Figure 8. Risk register template from VicRoads Major

Projects Division in Victoria, Australia.

.............

16

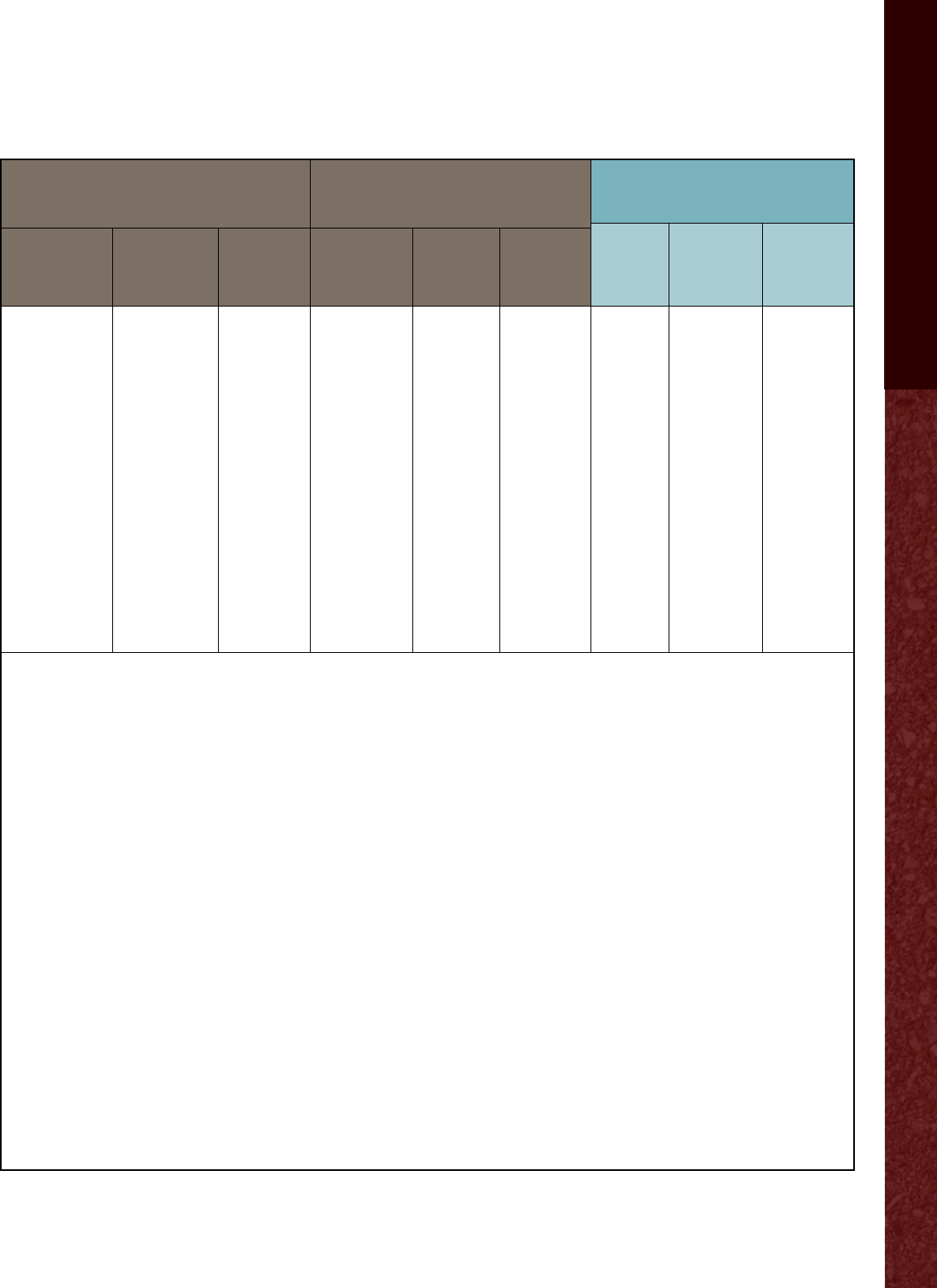

Figure 9. Risk register template from the Highways

Agency in England.

...........................

18

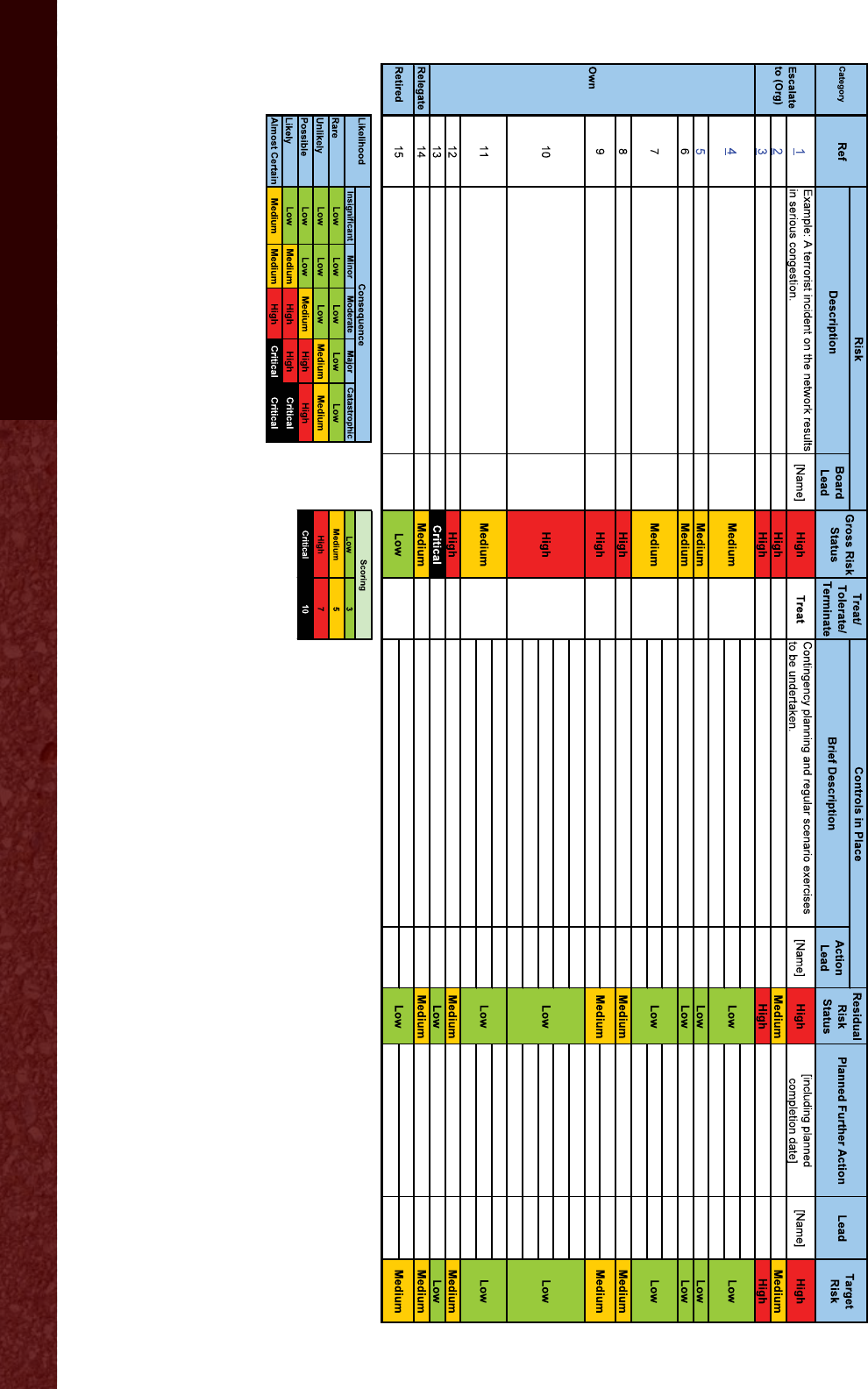

Figure 10. Heat map example.

...................

20

Figure 11. Risk assessment guidance from the Highways

Agency in England.

...........................

20

Figure 12. Risk management assessment guide from the

Highways Agency in England.

....................

21

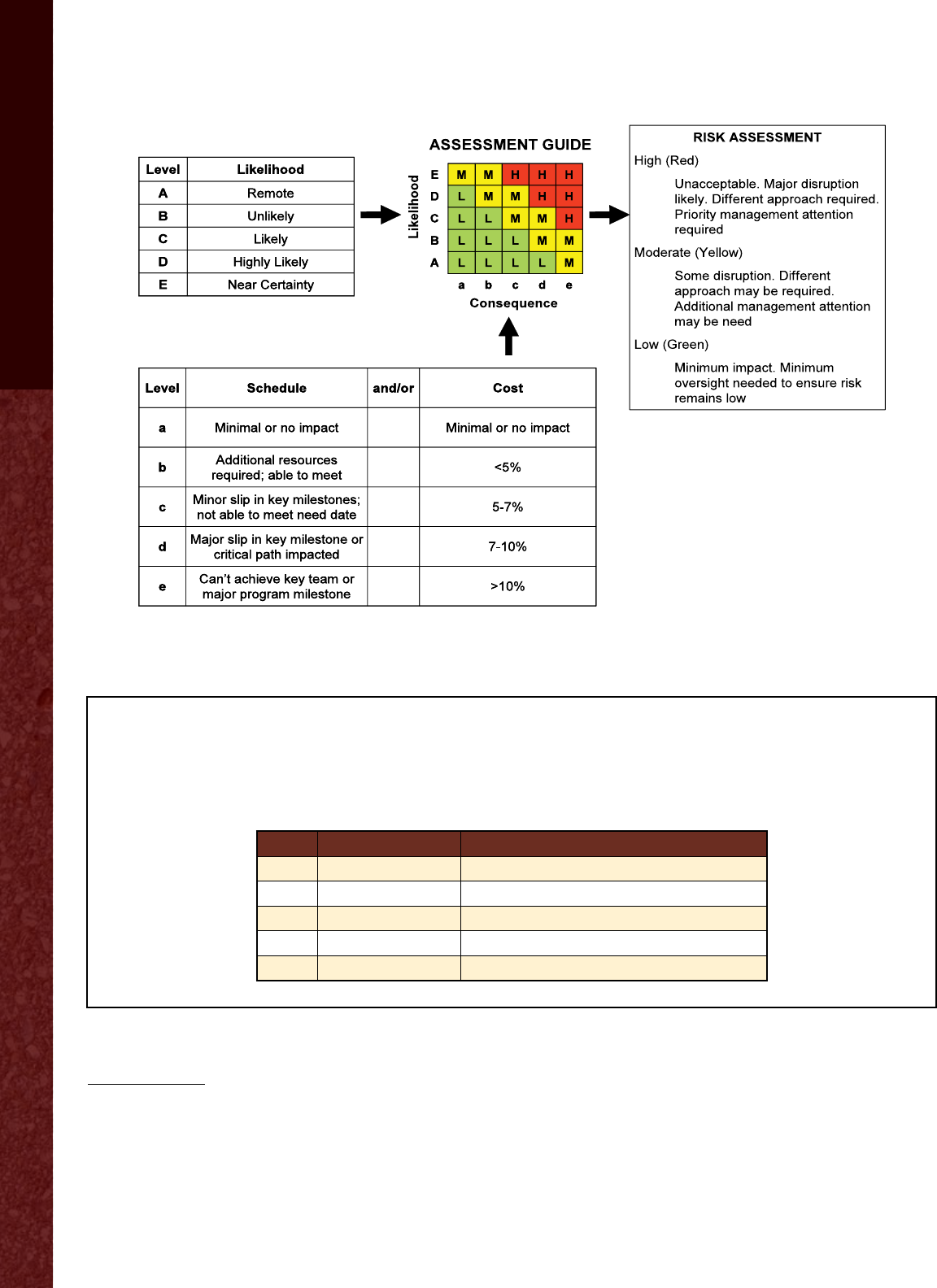

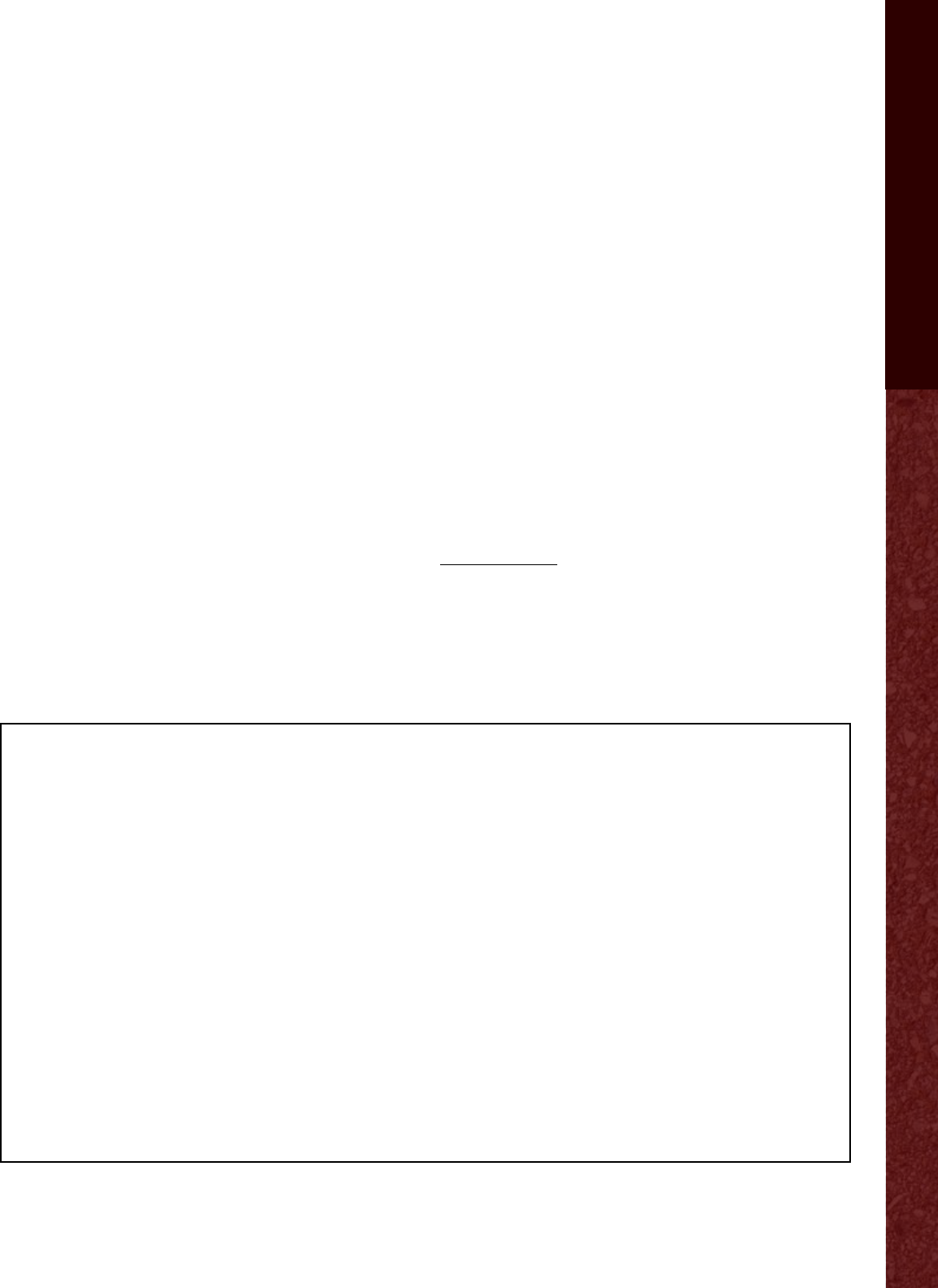

Figure 13. Risk management output

(Performance Audit Group, Transport Scotland).

.....

22

Figure 14. Program risk management plan example

(Transport and Main Roads, Queensland, Australia).

...

23

Figure 15. VicRoads Corporate Risk Management

Assessment Guide.

............................

27

Figure 16. Risk management framework

(Transport and Main Roads, Queensland, Australia)

...

28

Figure 17. Role description of the assistant director for

risk management at Transport and Main Roads,

Queensland, Australia.

.........................

29

Figure 18. Risk management roles and responsibilities

(Highways Agency, England).

....................

30

Figure 19. Risk management organizational structure

(VicRoads, Victoria, Australia).

...................

31

Figure 20. VicRoads corporate risk management

assessment scale.

.............................

32

Figure 21. Victorian Managed Insurance Authority

State Risk Register approach.

....................

32

Figure 22. M80 risk management approach

(VicRoads, Victoria, Australia).

...................

33

Figure 23. Highways Agency, England, risk escalation

process.

....................................

33

Figure 24. Risk framework maturity model

(VicRoads, Victoria, Australia).

...................

34

Figure 25. Asset management risk assessment

(Highways Agency, England).

....................

36

Figure 26. Geotechnical asset risk profile

(Highways Agency, England).

....................

37

Figure 27. Program risk analysis for Dutch waterways

(Rijkswaterstaat, the Netherlands).

................

37

Figure 28. Branch risk analysis with relation to agency

objectives (Transport and Main Roads, Queensland,

Australia).

...................................

39

Figure 29. Major risk bookmark (Transport and Main

Roads, Queensland, Australia).

...................

40

Figure 30. Cascading risk registers from project

to program to agency (Highways Agency, London,

England).

...................................

41

Figure 31. Project risk bookmark (Transport and Main Roads,

Queensland, Australia).

.........................

41

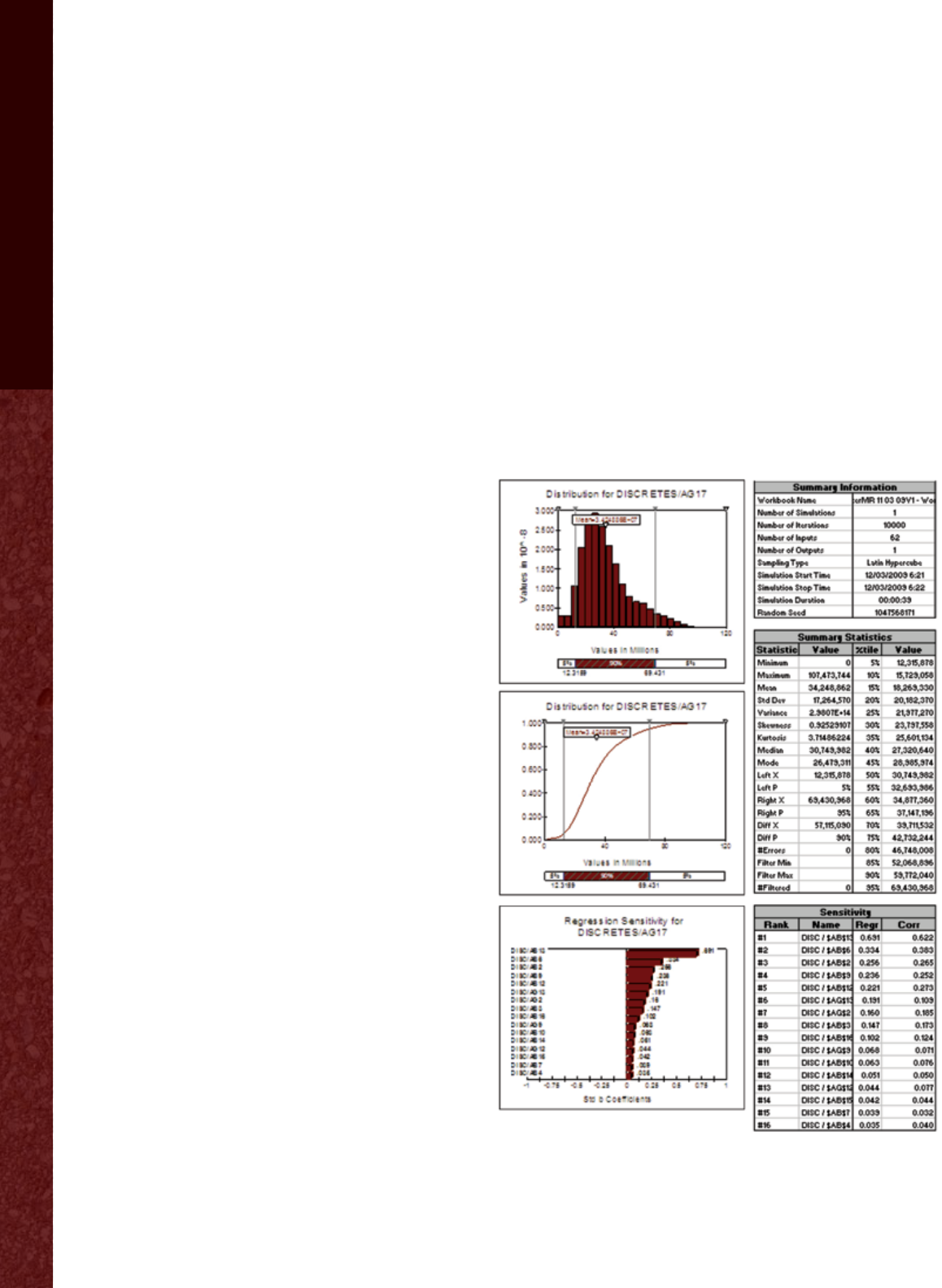

Figure 32. Range cost estimate from a risk-based

Monte Carlo analysis (Transport and Main Roads,

Queensland, Australia).

.........................

42

Figure 33. Project risk dashboard

(Transport and Main Roads, Queensland, Australia).

...

43

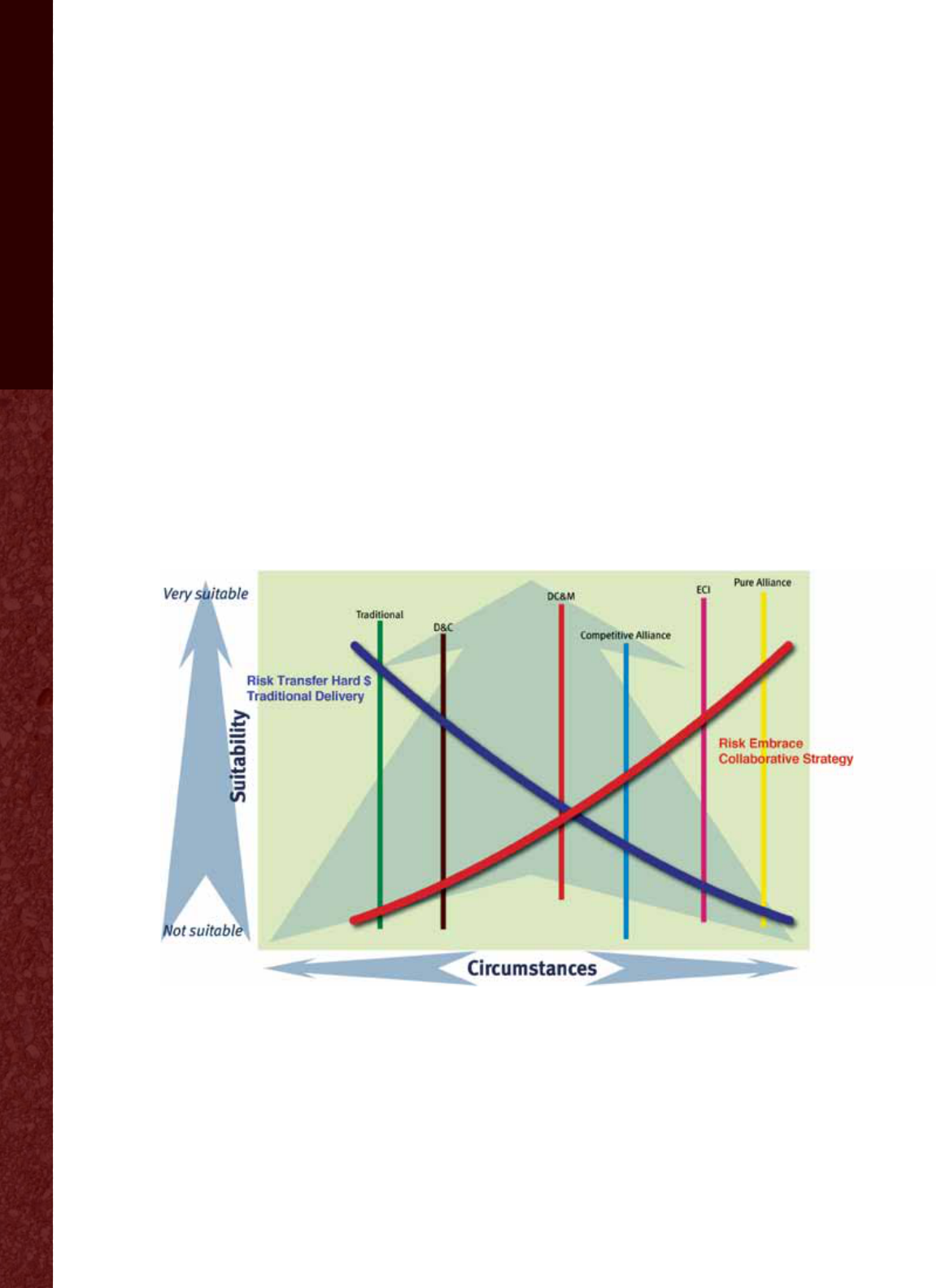

Figure 34. Risk allocation and project delivery selection

(Transport and Main Roads, Queensland, Australia).

...

44

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 1

Executive Summary

Background

Managing transportation networks, including agency

management, program development, and project

delivery, is extremely complex and fraught with

uncertainty. Administrators, planners, and engineers

coordinate a multitude of organizational and techni-

cal resources to manage transportation network

performance. While most transportation agency

personnel would say they inherently identify and

manage risk in their day-to-day activities, a recent

study found that only 13 State departments of

transportation (DOT) have formal enterprise risk

management programs and even fewer have a

comprehensive approach to risk management

at the agency, program, and project levels.

1

Risk management is implicit in transportation

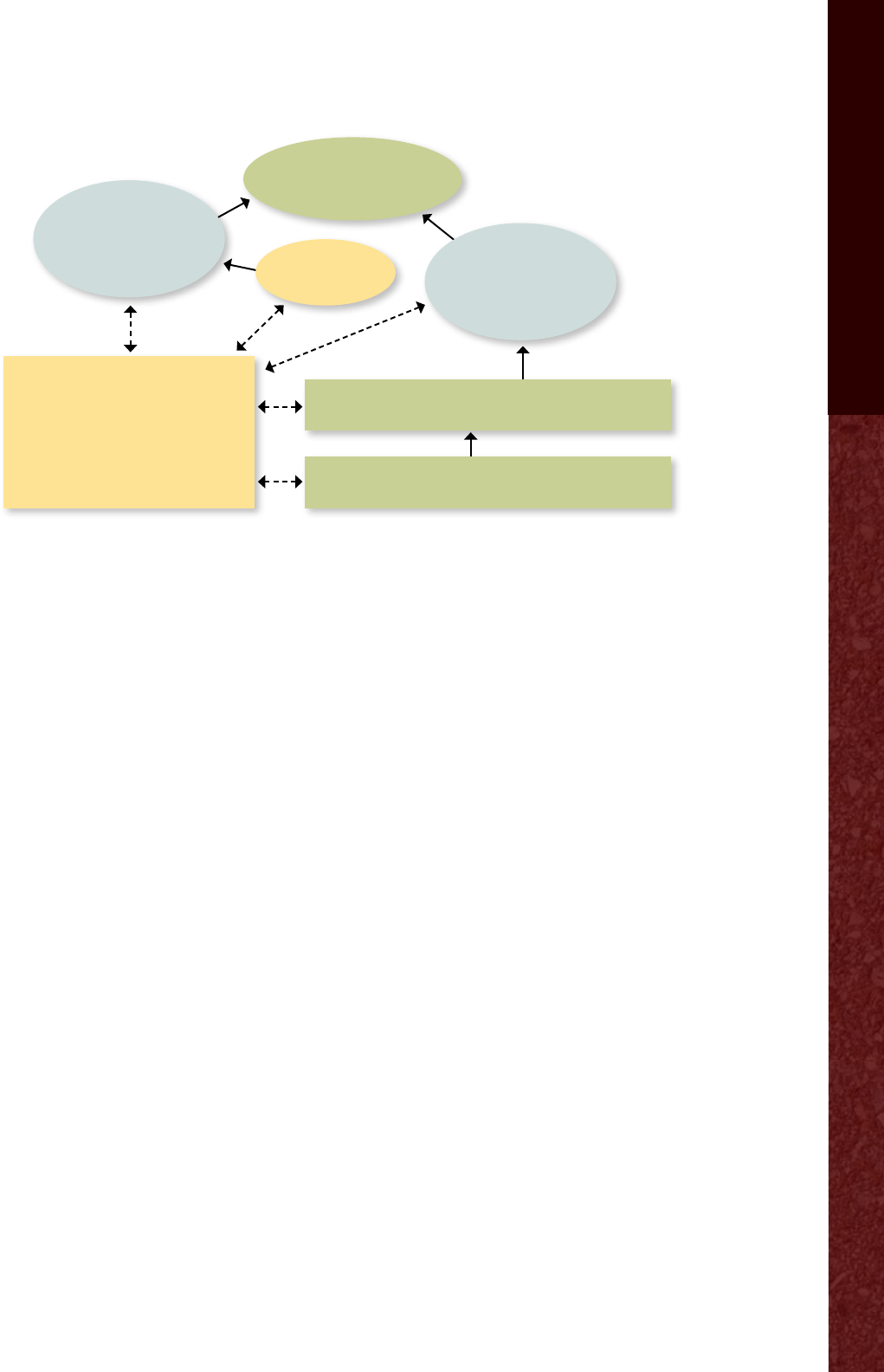

business practices (see figure 1). Transportation

agencies set strategic goals and objectives (e.g.,

the reliable and ecient movement of people and

1

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (2011).

Executive Strategies for Risk Management by State Depart-

ments of Transportation. NCHRP Project 20-24(74), National

Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation

Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC.

goods), but success is uncertain. Internal and

external risk events can impact the achievement of

these objectives. Likewise, agencies set perfor-

mance measures and develop asset management

systems to optimize investment decisions. Again,

risks can impact the achievement of performance

and assets. Risk is pervasive in transportation. It is

incumbent on transportation agencies to develop

explicit enterprise risk management strategies,

methods, and tools.

What is Risk Management?

The international standard ISO 31000 defines risk

as “the eects of uncertainty on objectives.”

2

In

its broadest terms, risk is anything that could be

an obstacle to achieving goals and objectives.

Risk management is a process of analytical and

management activities that focus on identifying

and responding to the inherent uncertainties of

managing a complex organization and its assets.

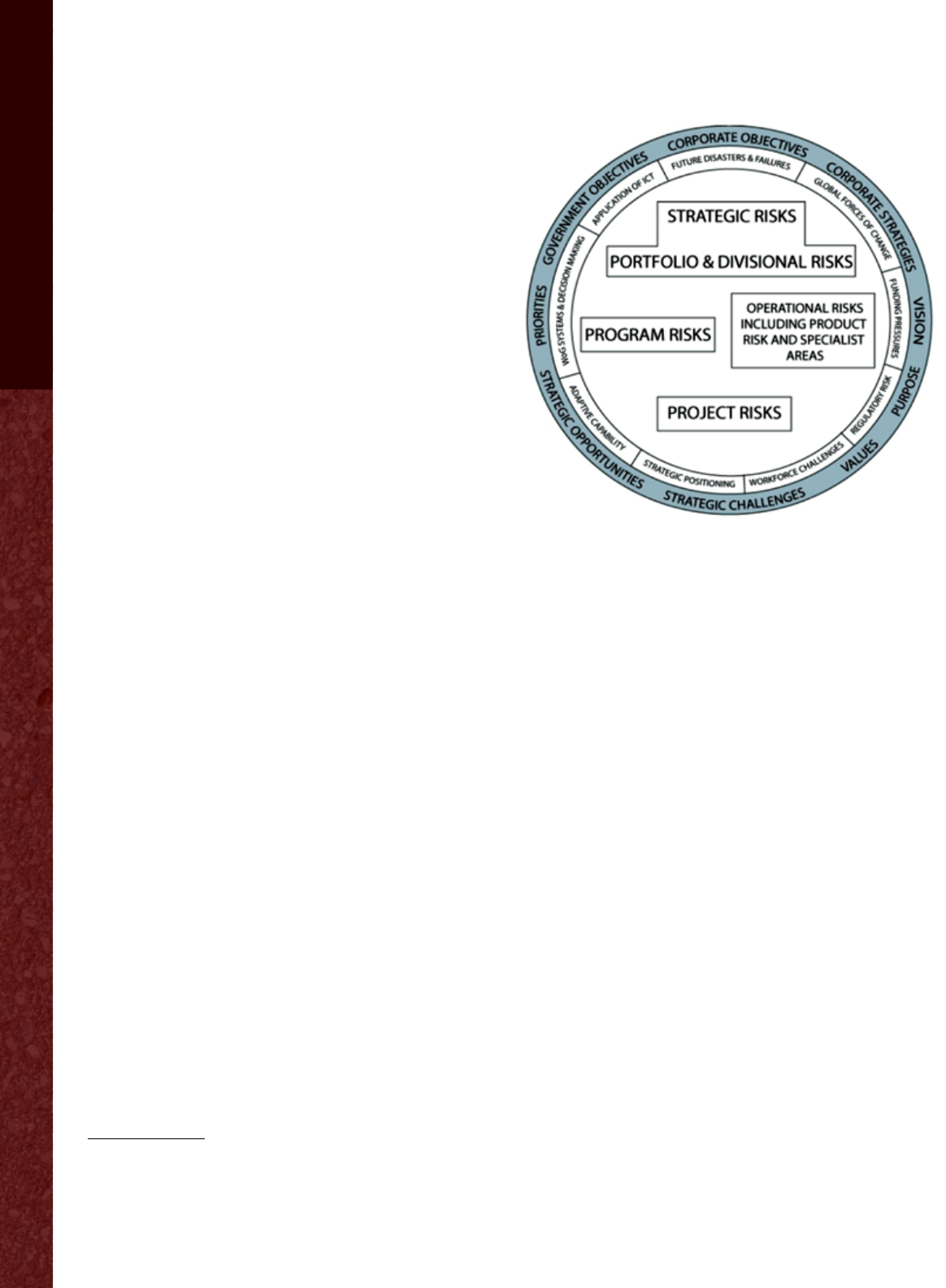

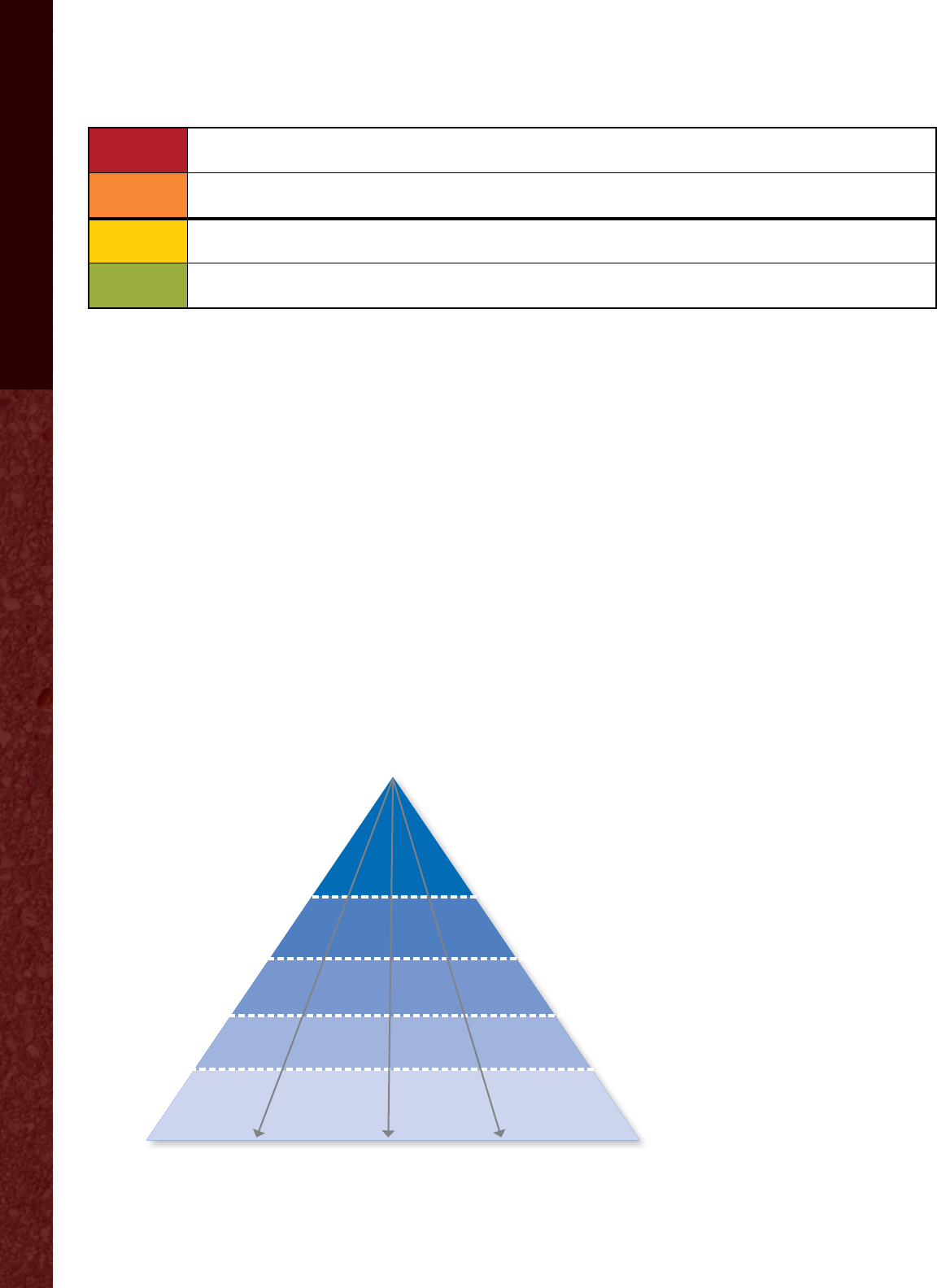

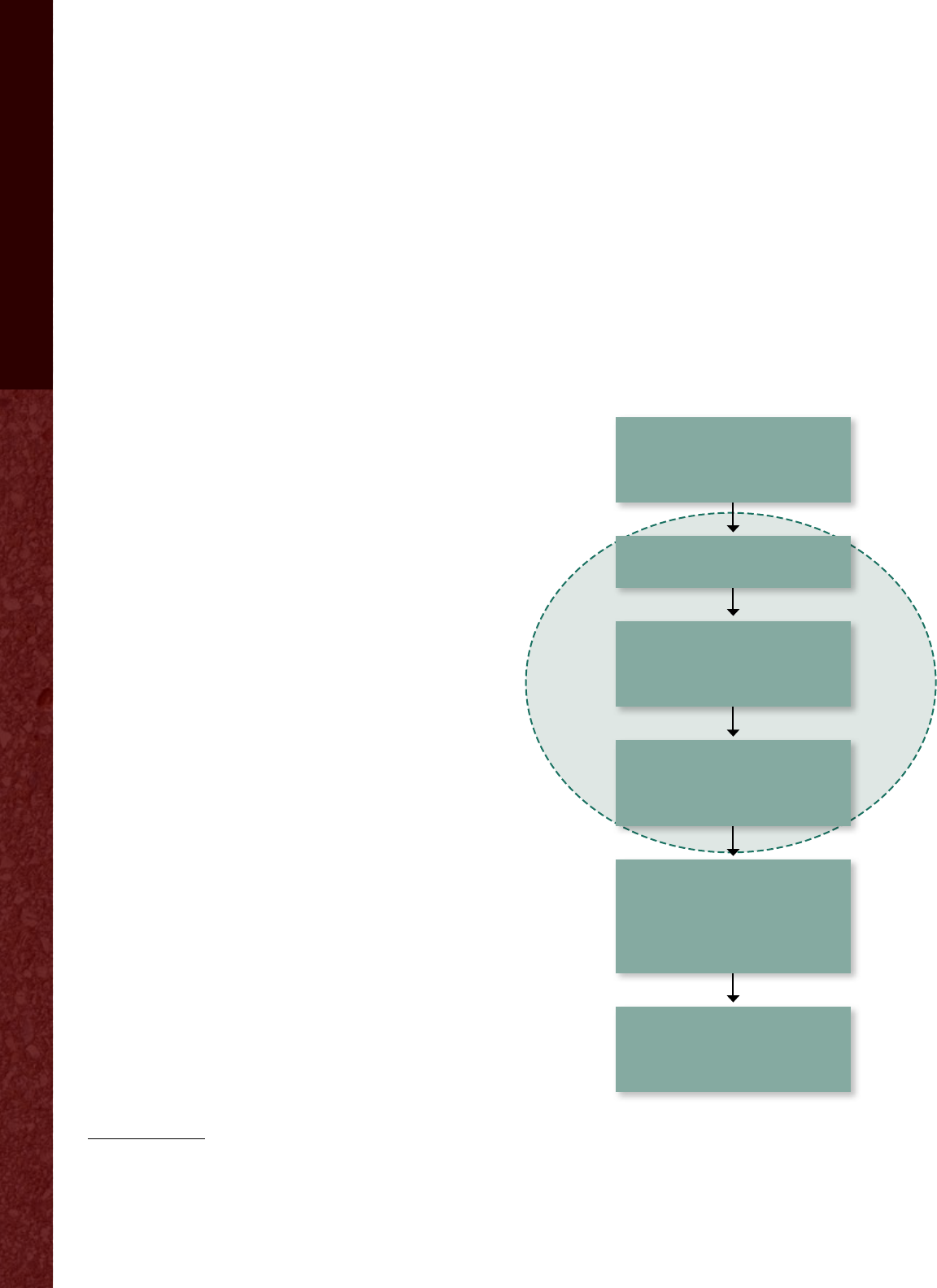

Risk can be managed at multiple levels (see figure

2). Enterprise risk management is a term that execu-

tives use when discussing risk. For this purpose,

enterprise risk management involves three levels—

agency, program, and project risk management.

Agency risk management is the responsibility of

highway agency executives. Executives benefit from

the process, but they are also responsible for defin-

ing and championing the process. Agency risks are

the uncertainties that can aect the achievement of

the agency’s strategic objectives (e.g., agency

reputation, data integrity, funding, safety, leader-

ship). Agency risk management is the consistent

application of techniques to manage the uncertain-

ties in achieving agency strategic objectives. There-

fore, agency risk management is not a task to

complete or a box to check, but a process to consis-

tently apply and improve. As we move down a layer,

risk management at the program level involves

managing risk across a network or multiple projects

(e.g., risks inherent in city or regional transportation

2

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

(2009). ISO 31000 Risk Management—Principles and

Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization,

Geneva, Switzerland.

Strategic

Objectives

Risk

Management

Asset

Management

Performance

Management

Figure 1. Relationship of risk management to transportation

agency management.

2 Executive Summary

planning, risk of material price escalation, design

standard changes, environment, structures). Finally,

risks may be unique to a specific project. Project risk

management occurs with sta familiar with the

specifics of that project and other technical experts

and stakeholders (e.g., utility relocation coordina-

tion, right-of-way purchase delays, geotechnical

issues, community issues). Figure 2 summarizes the

responsibility, type of risk, and risk management

strategies at these three levels.

Figure 2 describes many risk management strategies

highway agencies already practice in the United

States. Agency personnel manage risk daily. How-

ever, comprehensive risk management, from the

agency to the project level, is not common in the

United States.

3

This report describes the best prac-

tices of international organizations with the most

mature risk management programs. Adopting these

best practices will lead to improving agency gover-

nance structures, better aligning stakeholder func-

tions with facility user needs, saving short- and

long-term funds, reducing fatalities, and improving

other agency functions that have uncertainty.

3

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (2011).

Executive Strategies for Risk Management by State Depart-

ments of Transportation. NCHRP Project 20-24(74), National

Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation

Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC.

Purpose and Scope

From May 26 to June 12, 2011, a U.S. panel traveled

to Australia and Europe to learn from their signifi-

cant experience by conducting a scan of risk man-

agement practices for program development and

project delivery. The purpose of the scan was to

review and document international policies, prac-

tices, and strategies for potential application in the

Unites States. The team conducted meetings with

government agencies, academic researchers, and

private sector organizations that actively participate

in risk management eorts. The scan team also

visited project sites and personnel who were apply-

ing these practices. The scan team visited with

international organizations from the following:

New South Wales, Australia

Victoria, Australia

Queensland, Australia

London, England

Cologne, Germany

Rotterdam, Netherlands

Glasgow, Scotland

RESPONSIBILITY: Executives

TYPE: Risks that impact achievement of agency goals and objectives and involve

multiple functions

STRATEGIES: Manage risks in a way that optimizes the success of the organization

rather than the success of a single business unit or project.

RESPONSIBILITY: Program managers

TYPE: Risks that are common to clusters of projects, programs, or entire business units

STRATEGIES: Set program contingency funds; allocate resources to projects consist-

ently to optimize the outcomes of the program as opposed to solely projects.

RESPONSIBILITY: Project managers

TYPE: Risks that are specific to individual projects

STRATEGIES: Use advanced analysis techniques, contingency planning, and consistent

risk mitigation strategies with the perspective that risks are managed in projects.

AGENCY

PROGRAM

PROJECT

Figure 2. Levels of enterprise risk management (agency, program, and project).

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 3

Observations and Key Findings

The leading international transportation agencies

have mature risk management practices. They have

developed policies and procedures to identify,

assess, manage, and monitor risks. A brief summary

of the team’s observations includes the following:

Risk management supports strategic organiza-

tional alignment.

Mature organizations have an explicit risk

management structure.

Successful organizations have a culture of risk

management.

A wide range of risk management tools are in

use.

Risk management tools are key for program-

matic investment decisions.

A variety of risk management methods are

available.

Active risk communication strategies improve

decisionmaking.

Risk management enhances knowledge man-

agement and workforce development.

A fully functioning and mature risk management

program supports performance management and

asset management. It integrates strategic planning

with performance and asset management by focus-

ing on risks that could negatively impact overall

agency performance.

Benefits and Challenges of Formal

Risk Management

For agencies that do not currently conduct enter-

prise risk management, there is an investment to

begin. Developing an organizational structure and

investing in the development of methods and tools

are not trivial tasks. An understanding of the ben-

efits and challenges is helpful in developing an

enterprise risk management program.

Benefits

Helps with making the business case for

transportation and building public trust

Avoids or minimizes managing-by-crisis and

promotes proactive management strategies

Explicitly recognizes risks in multiple invest-

ment options with uncertain outcomes

Provides a broader set of viable solution

options earlier in the process

Communicates uncertainty and helps focus

on key strategic issues

Improves organizational alignment

Promotes an understanding of the repercus-

sions of failure

Helps apportion risks to the party best able to

manage them

Facilitates good decisionmaking and account-

ability at all levels of the organization

Challenges

Gaining organizational support for risk manage-

ment at all levels

Evolving existing organizational culture, which

can be risk averse

Developing and funding organizational

expertise for risk management

Implementing and embedding a new process

for risk management

Diculty in applying risk allocation alternatives

within organizational constraints

Lack of willingness to accept and address issues

that risk management will identify

Recommendations

The risk management scan team included Federal,

State, and private sector members with well over

100 years of combined experience in the operation,

4 Executive Summary

design, and construction of U.S. transportation

systems. Through this focused research study, the

team has gained a fresh perspective on how the U.S.

transportation industry can use risk management

practices to better meet its strategic objectives,

improve performance, and manage assets. The

following scan team recommendations oer a path

forward for the transportation community and will

help develop a culture of risk awareness and man-

agement in the United States:

1. Develop executive support for risk

management.

2. Define risk management leadership and

organizational responsibilities.

3. Formalize enterprise risk management

approaches using a holistic approach to sup-

port decisionmaking and improve successful

achievement of strategic goals and objectives.

4. Use risk management to reexamine existing

policies, processes, and standards.

5. Embed risk management in existing business

processes so that when asset, performance,

and risk management are combined, success-

ful decisionmaking ensues.

6. Identify risk owners and manage risks at the

appropriate level.

7. Use the risk management process to support

risk allocation in agency, program, and project

delivery decisions.

8. Use risk management to make the business

case for transportation and build trust with

transportation stakeholders.

9. Employ sophisticated risk analysis tools, but

communicate results in a simple fashion.

Implementation

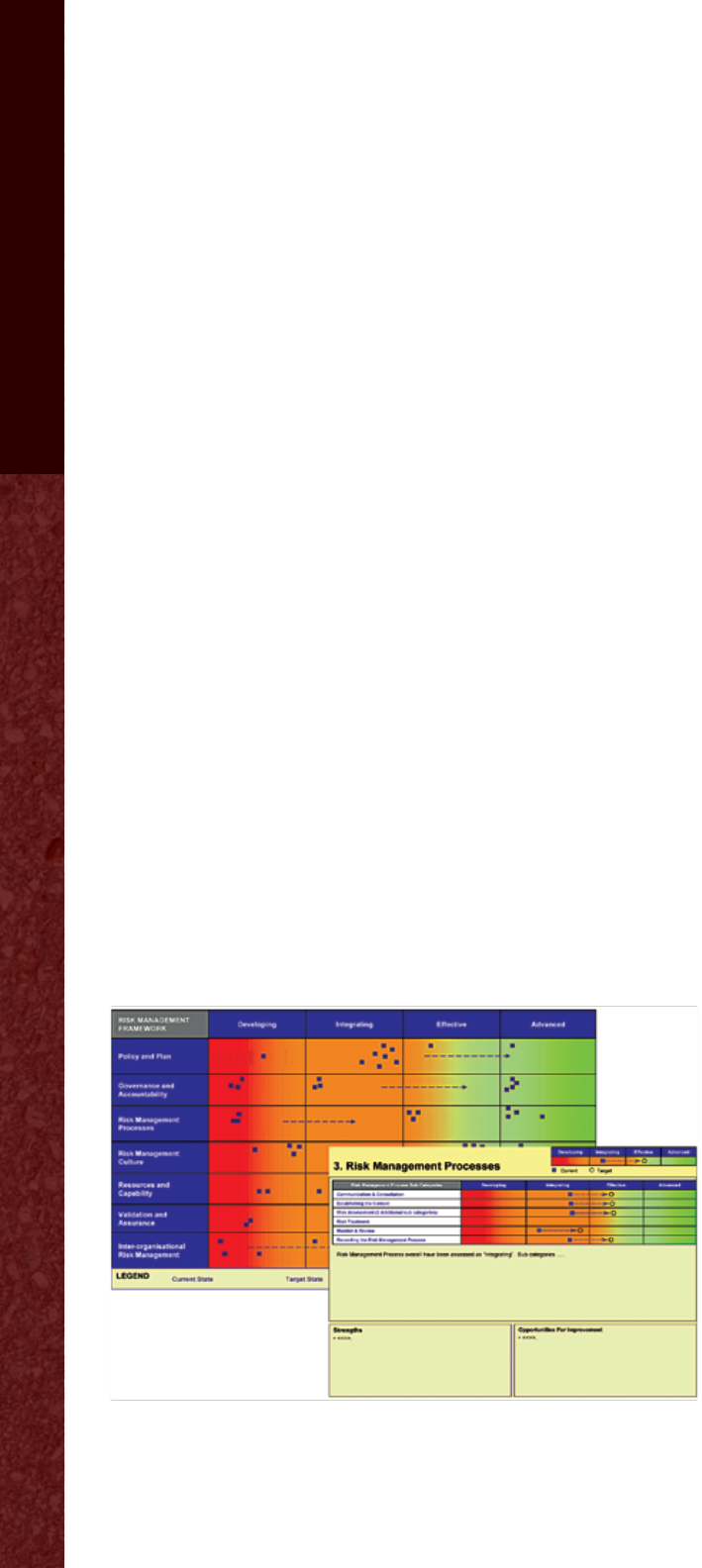

The risk management scan findings confirm that an

ecient and eective enterprise risk management

program is a powerful tool for the international

transportation agencies the team visited. The dem-

onstrated benefits for the agencies are both quanti-

tative, such as better controls over costs and

delivery schedules, and qualitative, such as less

likelihood of negative public relations issues. Risk

management provides information that allows

agencies to improve programs and projects by

making them more ecient. By identifying and

mitigating risks, agencies can avoid policies and

standards that are not practical for all cases. The

findings further confirm that risk management

programs can be a powerful tool and unifying

systems approach for State agencies. While today

each U.S. highway agency diers in its level of risk

management maturity, it seems reasonable that the

implementation activities associated with this scan

should advance enterprise risk management in State

agencies throughout the country. That is, agencies

need to do risk management at the agency, pro-

gram, and project levels to be fully successful.

The scan findings confirm the need for additional

implementation activities that fall into the categories

of research, training, governance, and communication

and marketing for knowledge transfer. The following

are some preliminary short- and long-term implemen-

tation suggestions to evolve and advance enterprise

risk management in U.S. highway agencies:

Conduct an executive-level risk management

workshop.

Host an international enterprise risk manage-

ment workshop.

Develop a guidebook on enterprise risk

management strategies, methods, and tools.

Develop and deploy risk management tools.

Develop risk management performance

measures.

Develop and implement risk management

assessment tools and a maturity model.

Introduce risk management case studies.

Activate an American Association of State

Highway and Transportation Ocials risk

management subcommittee (elevate from

a technical committee).

Update risk management training to incorpo-

rate lessons learned from the scan.

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 5

Most agencies would agree that they already do

some form of risk management, but few agencies

have reached the level of maturity found in the host

countries visited on this scan. The implementation

strategies will serve as a means to transfer the

practices from Australia and Europe that could

significantly improve highways and highway trans-

portation services in the United States. This technol-

ogy transfer enables innovations to be adapted and

put into practice much more eciently without

spending scarce research funds to re-create

advances already developed by other countries.

Successful implementation in the United States of

the world’s best practices is the goal of the eort.

Reader’s Guide to the Report

The report combines a discussion of common

practices and illustrative case studies of risk man-

agement in Australia and Europe with critical analy-

sis of the applicability of these techniques to U.S.

agencies and culture. Whenever possible, parallel

U.S. examples are provided to amplify techniques

that are directly applicable. This report begins with a

discussion of risk management strategies and tools

that are common to the agencies on the scan. It then

discusses applications of risk management at the

agency, program, and project levels. The document

concludes with recommendations for developing

risk management practices in the U.S. transportation

sector.

The report is designed to provide information to

various users in a number of ways. Chapter 3 on

agency risk management focuses on providing

information to transportation executives and inspir-

ing them to lead change in their agencies. It is rich

with examples of how transportation agencies can

benefit from a holistic approach to risk manage-

ment. Chapter 4 on program risk management is

geared to program managers and leaders of disci-

pline groups. It provides more comprehensive

approaches to aligning various risk management

eorts across highway agencies. Chapter 5 on

project risk management provides project managers

with examples and tools to improve their project

performance. Chapter 6 provides a framework for

enterprise risk managers in highway agencies to

implement risk management in their organizations

and support growth of risk management in the U.S.

transportation community.

6

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 7

CHAPTER 1:

Introduction

Background and Purpose

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

(NCHRP) studies have found that U.S. highway

agencies have only recently begun to develop

formal risk management policies and procedures at

the enterprise, program, and project levels.

4

Formal

enterprise risk management has the potential to

help highway agencies communicate uncertainty,

gain trust from the public, make the business case

for more public funding, provide a broader set of

viable solution options earlier in the process, and

apportion risks to the party best able to manage

them. The public highway sector trails public sector

counterparts such as the U.S. Department of Energy

and the Federal Transit Administration in risk man-

agement application at the project level. Adding

urgency is the current Federal highway reauthoriza-

tion plan, which is based on performance measures

that will necessitate an integrated risk management

approach to succeed.

Planners, engineers, and project and administrative

managers must coordinate a multitude of human,

organizational, technical, and natural resources.

Quite often, the engineering and construction

complexities are overshadowed by societal, eco-

nomic, and political challenges. Financial uncertain-

ties are pervasive and create cascading impacts

throughout transportation organizations because of

the length of the planning, design, and construction

process. Clearly, the tools of risk management

belong in the broad set management tools required

for successful delivery of national and State highway

facilities.

4

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (2011).

Executive Strategies for Risk Management by State Depart-

ments of Transportation. NCHRP Project 20-24(74), National

Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation

Research Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC,

May 2011.

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (2010).

Guidebook on Risk Analysis Tools and Management Practices

to Control Transportation Project Costs. NCHRP Report 658,

ISBN 978-0-309-15476-5, National Cooperative Highway

Research Program, Transportation Research Board of the

National Academies, Washington, DC, June 2010, 120 pp.

The purpose of this scan was to examine risk

management programs and practices in other

countries that actively assess transportation system

performance risks and manage them through a risk

management process. The scan objectives were to

document lessons learned from public agencies

that are administering mature risk management

programs under a variety of programmatic

strategies and project delivery methods. The

scan focused on risk identification, analysis, and

management techniques that result in successful

program delivery and enhanced stakeholder com-

munications. The scope of this scan was limited to

an exploration of risk management processes, tools,

documentation, and communication. Risk manage-

ment strategies, methods, and tools used by inter-

national agencies are the key information obtained

by this scan.

Methodology

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and

the American Association of State and Highway

Transportation Ocials (AASHTO) jointly sponsored

this scan with the cooperation of NCHRP. The scan

topic was selected by the Transportation Research

Board’s (TRB) NCHRP Panel 20-36 from a number

of competing proposals for the 2011 funding cycle.

After the proposal was accepted, Daniel D’Angelo,

deputy chief engineer and director of design for

the New York State Department of Transportation

(DOT), and Joyce Curtis, associate administrator

of FHWA’s Oce of Federal Lands Highway, were

appointed scan cochairs. They joined representa-

tives from the public and private sectors to

represent a cross-section of the industry. The team

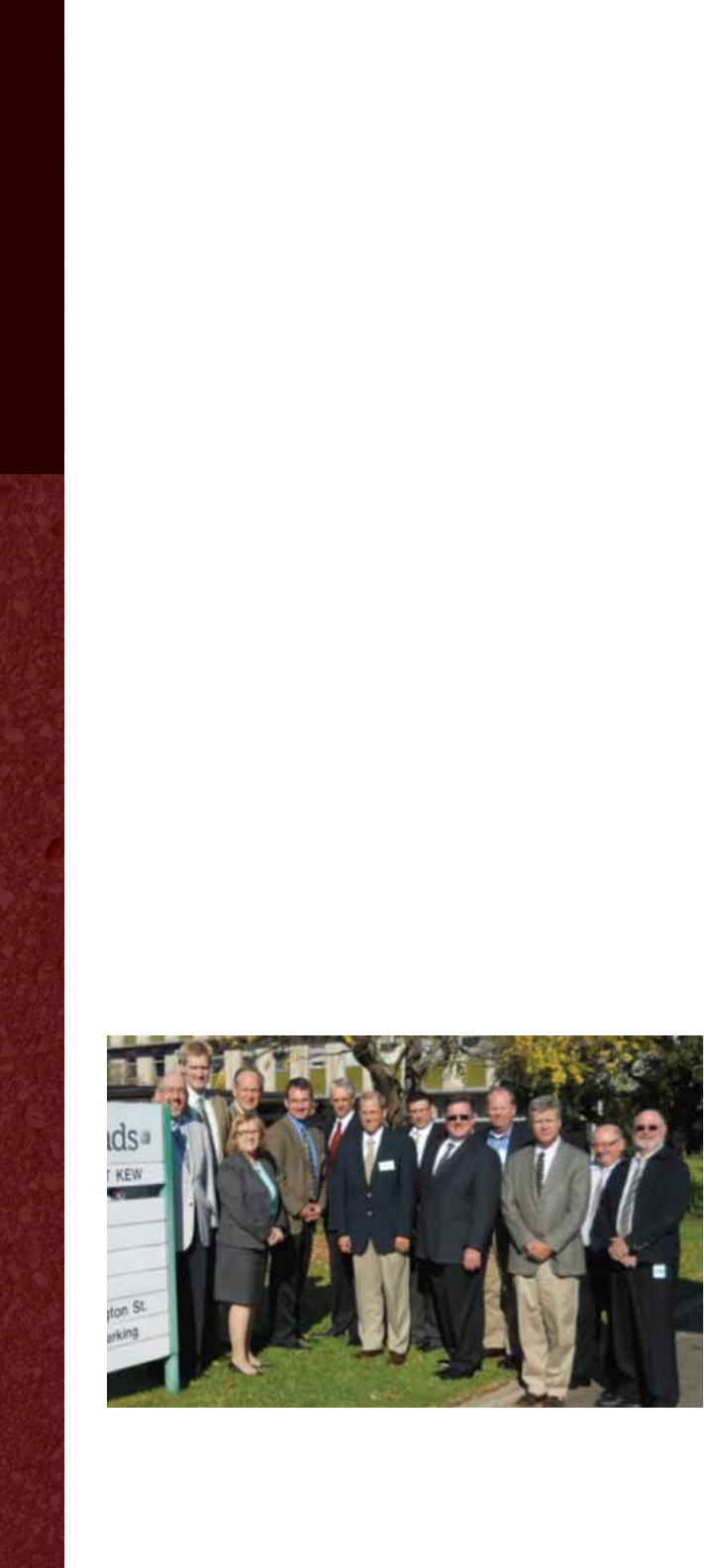

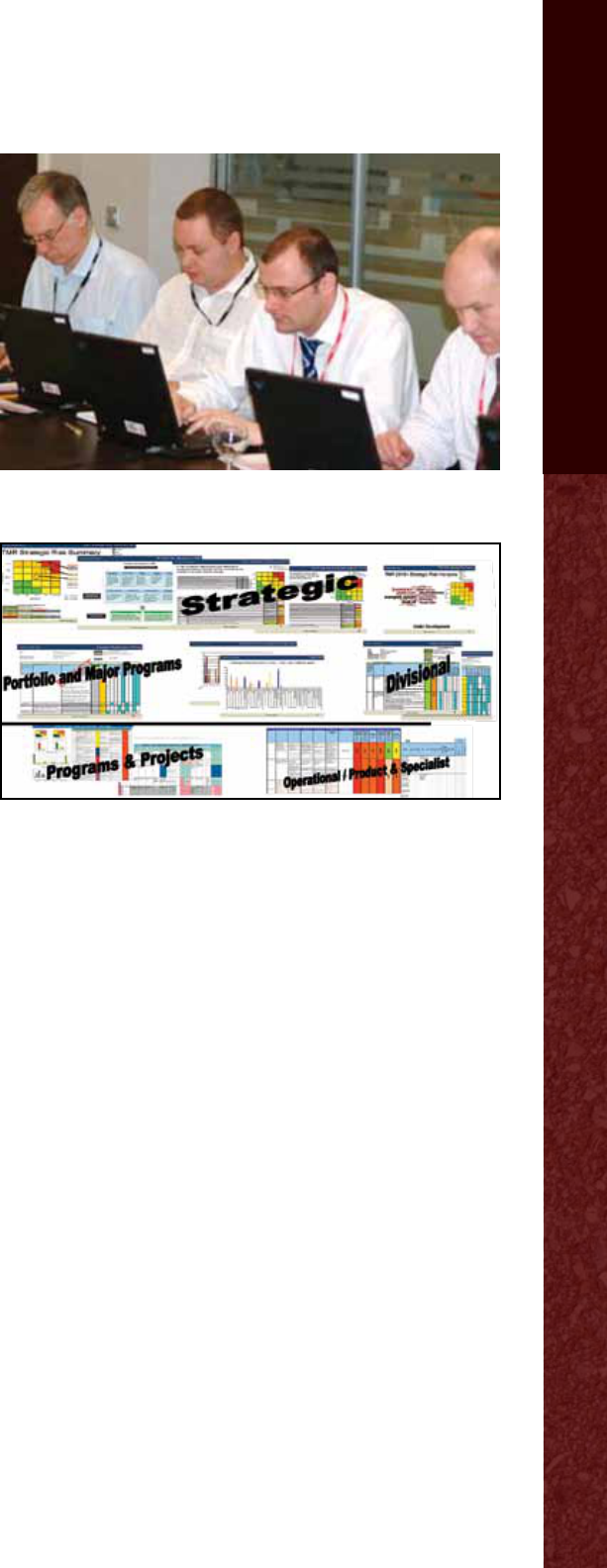

members are shown in figure 3 (see next page) and

their aliations are listed below. Contact information

and biographical sketches for the scan team

members are in Appendix A.

✓Formal risk management improves

decisionmaking and accountability

at all levels of the organization.

8 Chapter 1: Introduction

Joyce Curtis (FHWA cochair), associate admin-

istrator, FHWA Oce of Federal Lands Highway

Daniel D’Angelo, P.E. (AASHTO cochair),

deputy chief engineer and director of design,

New York State DOT

Keith R. Molenaar, Ph.D. (report facilitator),

professor and chair, University of Colorado

Boulder

Joseph S. Dailey, Wyoming Division

administrator, FHWA

Steven D. DeWitt, P.E., chief engineer,

North Carolina Turnpike Authority

Michael J. Graf, program management

improvement team leader, FHWA

Timothy A. Henkel, assistant commissioner,

Minnesota DOT

John B. Miller, Ph.D., president, Barchan

Foundation, Inc.

John C. Milton, Ph.D., P.E., director of

enterprise risk and safety management,

Washington State DOT

Darrell M. Richardson, P.E., assistant State

roadway design engineer, Georgia DOT

Robert E. Rocco, associate vice president

and risk manager, AECOM Transportation

The next step was to conduct a desk scan to select

the most appropriate countries for the scan team

to visit. The objective was to maximize the time the

panel spent reviewing its topics of interest. The desk

scan employed a two-tier methodology of literature

review and synthesis. The methodology provided for

data collection from government agencies, profes-

sional organizations, and experts who are most

advanced in the scan topics. Given the wide variety

of scan topics and the relatively short time in which

to collect information, the desk scan did not act

as an all-inclusive study of global activities, but it

provided concrete quantitative information to

select the most appropriate scanning partners.

The literature review focused on gathering docu-

ments that describe risk management organizational

structures, practices, and published guidance.

Document types, in order of importance, included

government reports, journal articles, conference

proceedings, periodical articles, and Web docu-

ments. Government reports are the most dicult

to locate. These documents were found through

previous scans and on governmental Web sites. The

main search engine for the journals and conference

proceedings is the Ei Compendex database.

Ei CompendexWeb is a comprehensive bibliographic

database of engineering research literature, contain-

ing references to more than 5,000 engineering

journals and conferences. Also useful was TRB’s

database of papers and conference proceedings.

World Wide Web searches yielded perhaps the most

useful results for this report. The scan employed

Google Scholar as the main Web search engine.

Three primary selection criteria were

analyzed for this desk scan: (1) risk

management organizational structure,

(2) transferability of practices to the

United States, and (3) adoption of ISO

31000 Risk Management standards.

Each agency’s organizational structure

was analyzed to see if it defined risk

management as a specific organizational

function. The applicability of an organi-

zation’s risk management practices to

the United States was also examined.

This was done by comparing the plan-

ning, design, and operations functions

to the United States. The government’s

political and economic structures were

also considered. The number of times

each agency was visited on past scans

Figure 3. U.S. scan team.

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 9

was used as an indicator of transferability of

practices. Finally, countries were selected on the

basis of their adoption of the ISO 31000 standard.

This standard is important because it provides the

framework around which an international commu-

nity of risk managers can be established. A country

that has ocially adopted this standard would be

more accessible to an investigation.

The results of the desk scan were presented to the

U.S. scan team at a Washington, DC, meeting to

select the host countries. The team also used the

meeting to finalize a panel overview document,

which was sent to the host countries to prepare

them for the U.S. delegation. The panel overview

explained the background and scope of the scan,

sponsorship, team composition, topics of interest,

and tentative itinerary.

Before conducting the scan, the team prepared a

comprehensive list of amplifying questions to further

define the panel overview and sent it to the coun-

tries it planned to visit. Some of the host countries

responded to the questions in writing before the

scan, while others used them to organize their

presentations. The team attempted to craft ques-

tions that were precise enough to elicit the informa-

tion that it anticipated, yet open-ended enough

that the host countries could bring new ideas—not

envisioned by the U.S. scan team—to light. The team

was successful in its assembly of the questions, as

documented throughout this report. The amplifying

questions are in Appendix B.

The delegation traveled to Australia and Europe

from May 26 to June 12, 2011. The team visit con-

sisted of a combination of meetings with highway

agencies and practitioners and site visits. The scan

team met with representatives of the following

organizations:

Roads and Trac Authority, Sydney, Australia

VicRoads, Melbourne, Australia

Transport and Main Roads, Brisbane, Australia

Federal Highway Research Institute (BASt),

Cologne, Germany

Ministry of Transport, Public Works, and Water

Management, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Transport Scotland, Glasgow, Scotland

Highways Agency, London, England

The team met with these agencies in a series of

day-long interviews. The team followed the amplify-

ing questions to ensure consistency in data collec-

tion. The team also collected documentation of risk

management policies and procedures from the

agencies. The results of this report are based on the

desk scan, the interviews and documents collected

in the interviews, and the synthesis of the scan team

members during and after the visits.

10

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 11

CHAPTER 2:

Common Definitions, Strategies,

and Tools for Risk Management

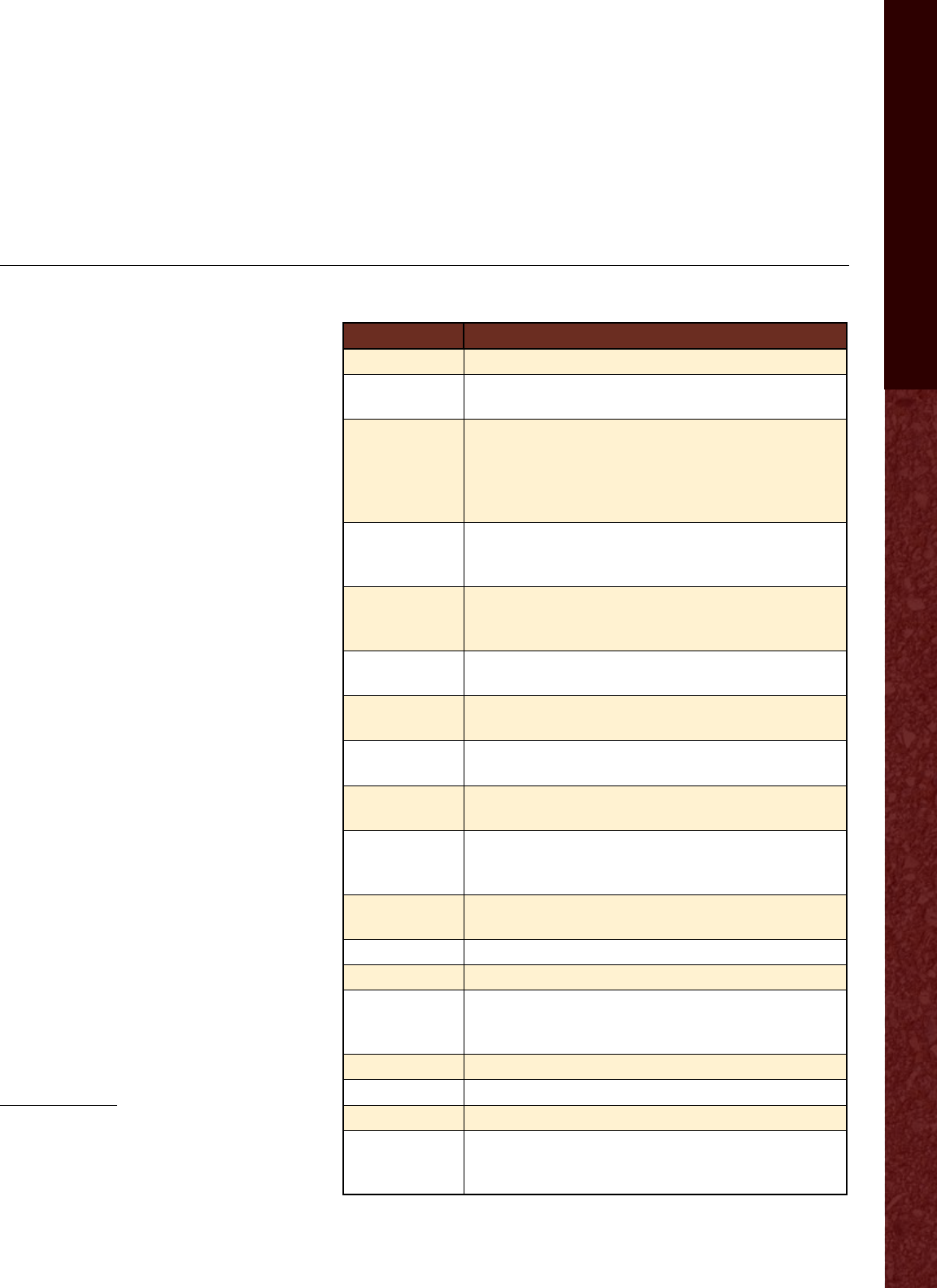

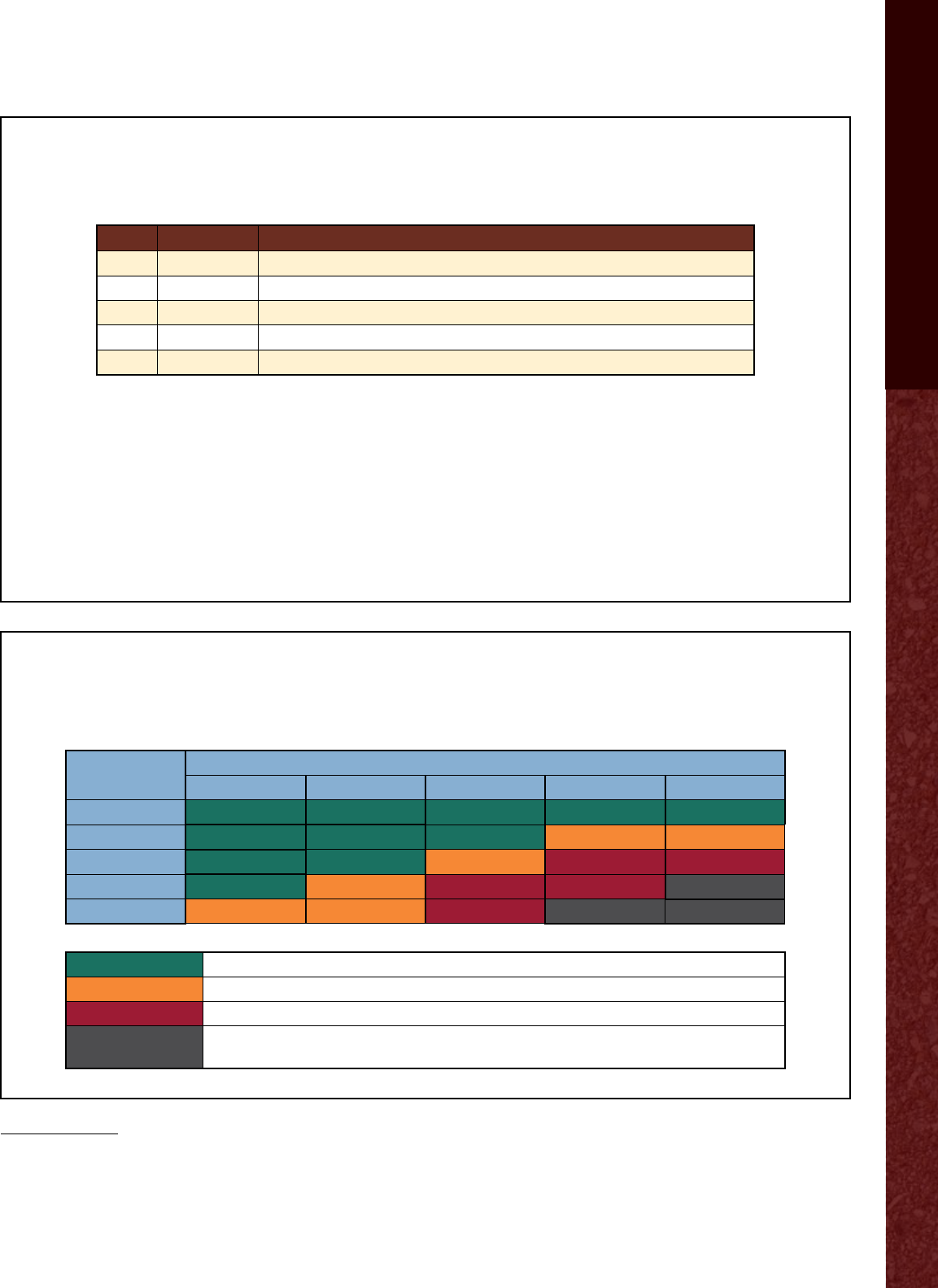

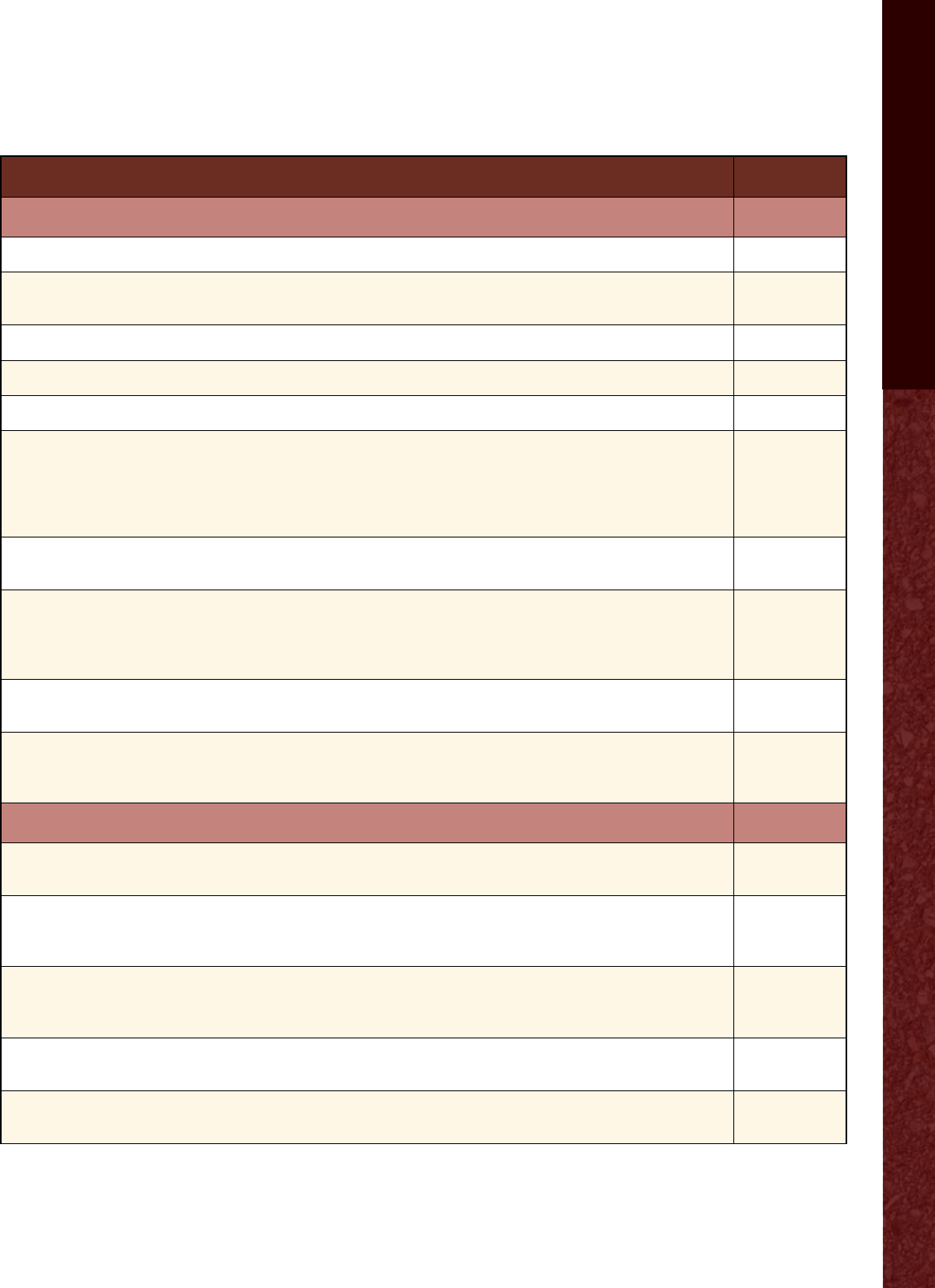

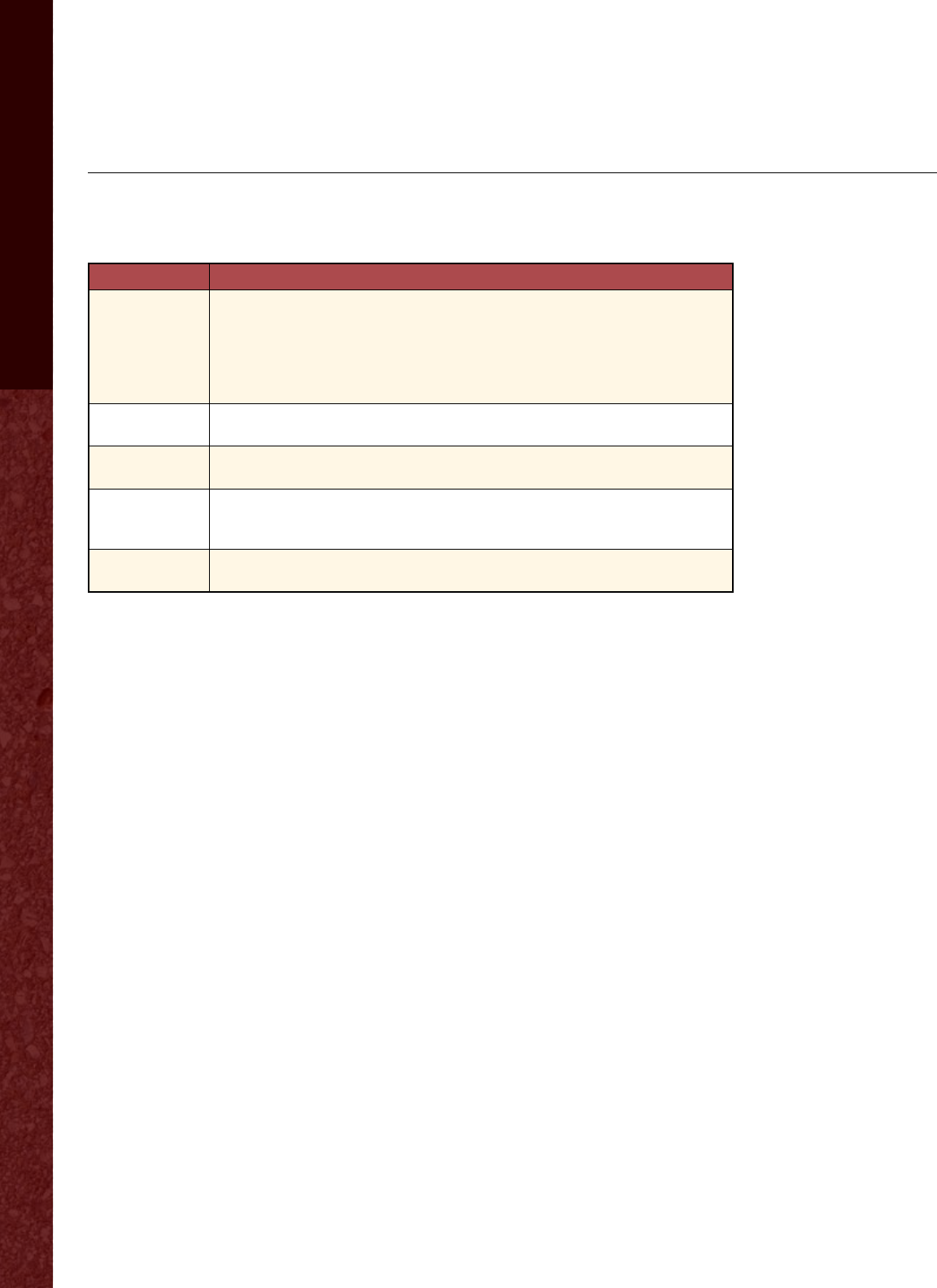

Table 1. Risk management definitions (from ISO 31000).

Term ISO 31000 Definition

Risk Effect of uncertainty on objectives

Risk

Management

Coordinated activities to direct and control an

organization with regard to risk

Risk

Management

Framework

Set of components that provide the foundations

and organizational arrangements for designing,

implementing, monitoring, reviewing, and

continually improving risk management throughout

the organization

Risk

Management

Policy

Statement of the overall intentions and direction of

an organization related to risk management

Risk

Management

Plan

Scheme within the risk management framework

specifying the approach, management components,

and resources to be applied to risk management

Risk Attitude Organization’s approach to assess and eventually

pursue, retain, take, or turn away from risk

Risk

Identification

Process of finding, recognizing, and describing risks

Risk

Assessment

Overall process of risk identification, risk analysis,

and risk evaluation

Risk Analysis Process to comprehend the nature of risk and

determine the level of risk

Risk

Evaluation

Process of comparing the results of risk analysis

with risk criteria to determine whether the risk and/

or its magnitude is acceptable or tolerable

Event Occurrence or change of a particular set of

circumstances

Likelihood Chance of something happening

Consequence Outcome of an event affecting objectives

Level of Risk Magnitude of a risk or combination of risks,

expressed in terms of the combination of

consequences and their likelihood

Risk Treatment Process to modify risk

Control Measure that is modifying risk

Residual Risk Risk remaining after risk treatment

Monitoring Continual checking, supervising, critically observing,

or determining the status to identify change from

the performance level required or expected

Introduction

Leading transportation agencies use

common strategies and tools for risk

management. These strategies and tools

were found to be consistent throughout

Australia and the European countries

the scan team visited. While risk analysis

techniques can be mathematically

complex and rigorous, the resulting

strategies and application tools are

simple. They communicate risk informa-

tion simply to decisionmakers. This

chapter presents risk management

definitions and the most common

strategies and tools. It provides a

foundation for the discussion of

agency, program, and project risks

in the chapters that follow.

Risk Management Definitions

While the vocabulary of risk manage-

ment terms varies slightly from agency

to agency, the fundamental definitions

are consistent throughout the globe.

Multiple industry organizations define

risk terms in an attempt to provide

standardization. The scan team found

that all the agencies in Australia and the

majority of agencies in Europe visited on

this scan refer to the definitions from the

ISO 31000 Risk Management—Principles

and Guidelines.

5

The most pertinent

definitions for this report are in table 1.

In addition to the ISO 31000 definitions,

a number of organizations have created

risk management definitions to clarify

5

International Organization for Standardiza-

tion (ISO) (2009). ISO 31000 Risk Manage-

ment—Principles and Guidelines. International

Organization for Standardization, Geneva,

Switzerland.

12 Chapter 2: Common Definitions, Strategies, and Tools for Risk Management

the process. Appendix D compares the primary

definitions and summarizes the terminology used

in this report. Appendix D cites some of the more

prominent national and international documents,

including the FHWA Guide to Risk Assessment and

Allocation for Highway Construction Management,

6

the NCHRP Guide for Managing NEPA-Related and

Other Risks in Project Delivery,

7

the NCHRP Guide-

book on Risk Analysis Tools and Management

Practices to Control Transportation Costs,

8

the

Project Management Institute’s Project Manage-

ment Body of Knowledge,

9

the Project Management

Institute’s Standard for Program Management,

10

and the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations

of the Treadway Commission’s Enterprise Risk

Management—Integrated Framework.

11

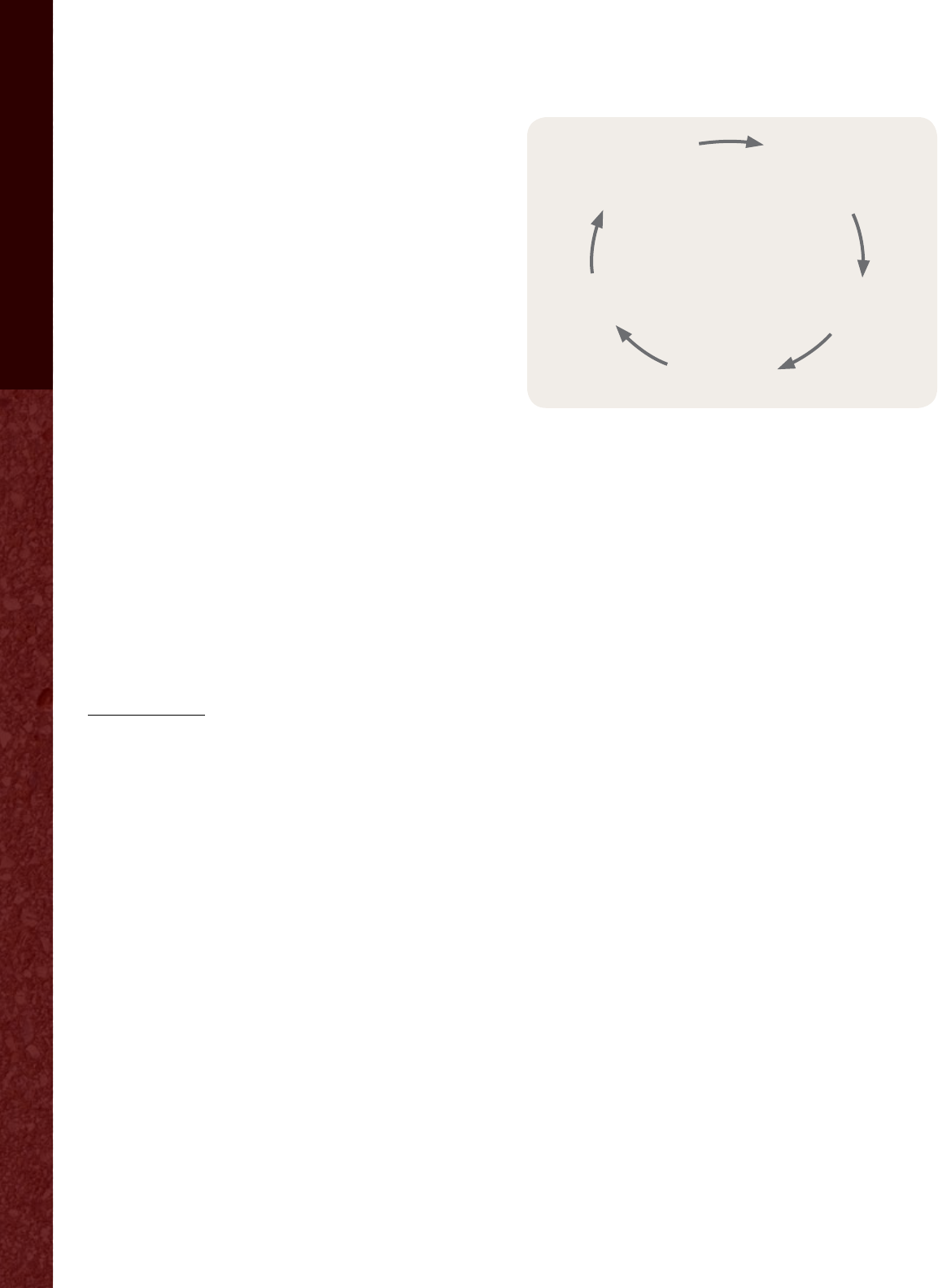

Risk Management Process

Several risk management steps (i.e., the risk man-

agement process) apply to all levels of transporta-

tion organizations. The guides from the Project

Management Institute, ISO, NCHRP, and FHWA

each have similar steps. Figure 4 outlines five steps

that have proven to be eective in managing risk:

(1) identification, (2) analysis, (3) evaluation,

(4) treatment, and (5) monitoring and review. Also,

as shown in figure 4, the risk management process

should be iterative. This means the steps must be

6

Federal Highway Administration (2006). Guide to Risk

Assessment for Highway Construction Management. Report

FHWA-PL-06-032, U.S. Department of Transportation,

Washington, D.C.

7

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (2011).

Guide for Managing NEPA-Related and Other Risks in Project

Delivery. NCHRP Web-Only Document 183, National Coopera-

tive Highway Research Program, Transportation Research

Board of the National Academies, Washington, DC.

8

National Cooperative Highway Research Program (2010).

Guidebook on Risk Analysis Tools and Management Practices

to Control Transportation Project Costs. NCHRP Report 658,

ISBN 978-0-309-15476-5, National Cooperative Highway

Research Program, Transportation Research Board of the

National Academies, Washington, DC.

9

Project Management Institute (2004). A Guide to Project

Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). Project

Management Institute, Newton Square, PA.

10

Project Management Institute (2006). Standard for

Program Management. Project Management Institute,

Newton Square, PA.

11

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway

Commission (2004). Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated

Framework. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the

Treadway Commission, www.coso.org.

repeated over time. As risk treatment eorts

are implemented, some risks no longer apply,

some residual risk may remain, and some new

risks may be identified. The nature of transporta-

tion development, design, construction, and

operations requires an iterative and active risk

management process.

Brief descriptions of each step follow. More detailed

explanations with descriptions and examples of

these steps are provided throughout this report.

1. Risk identification is the process of determin-

ing which risks might aect objectives and

documenting their characteristics. Risk identi-

fication uses simple tools such as brainstorm-

ing and checklists. Risks can aect objectives

at the agency level (e.g., achievement of

strategic goals), the program level (e.g.,

management of critical assets), and the

project level (e.g., attainment of budget or

schedule commitments). Risk identification

should occur continuously throughout the

risk management process.

2. Risk analysis involves defining, quantitatively

or qualitatively, the consequence (i.e., impact)

and likelihood (i.e., probability) of a risk. Risk

analysis can use simple methods to describe

risks, such as probability and impact matrices,

or more sophisticated probabilistic methods,

such as three-point estimates or probability

functions and Monte Carlo simulations. More

qualitative methods typically apply when

analyzing strategic goals and related items.

Figure 4. Cyclical nature of the risk management process

(adapted from PMI and ISO 31000).

RISK

MANAGEMENT

PROCESS

Monitoring

and Review Identification

Analysis

Treatment

Evaluation

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 13

More quantitative methods apply when analyz-

ing cost and schedule estimates or complex

design decisions.

3. Risk evaluation involves the process of

comparing the results of risk analyses with an

agency’s level of risk tolerance. If risks are too

great, action (i.e., risk treatment) will need to

be taken. Risk evaluation presupposes that an

agency has defined its risk tolerance and is

prepared to take action if a risk’s consequence

and likelihood are too great.

4. Risk treatment involves a risk response and

risk modification. Common options involve

avoidance, mitigation, or transference of the

risk. Risk avoidance is the best option if the

agency’s goals can still be achieved when the

risk is avoided. Mitigation typically involves

making an investment to reduce the conse-

quence or likelihood of a risk. Transference

involves allocating the consequence of the risk

to another party (e.g., a contractor), but there

is typically a price to transferring the risk

because the other party must mitigate the risk.

The fundamental tenets of risk transference

include allocating risks to the party best able

to manage them, allocating risks in alignment

with agency goals, and allocating risks to

promote team alignment with customer-

oriented performance goals.

5. Risk monitoring and review are the capture,

analysis, and reporting of risk status in relation

to performance. Risk monitoring and review

typically employ a risk management plan to

monitor risk status and identify changes from

the performance level required or expected.

Risk monitoring and review assist in contin-

gency tracking and resolution.

Structures for Successful Risk

Management

The scan team found structures for successful risk

management. Explicit structures can be shown with

organization charts and defined risk manager roles

and responsibilities, as described in Chapter 3. The

risk management policies described in Chapter 3 are

also a key to success. However, explicit structures

and policies are only part of a successful strategy.

The risk workshops and risk registers described in

this chapter are key tools found in each agency

visited on the scan. The outcome of these structures,

policies, and tools must be comprehensive risk

management plans and risk management communi-

cation. The most mature risk management organiza-

tions have structures that encompass the strategies

and tools described at the agency, program, and

project levels, explained in Chapters 2 through 5 of

this report.

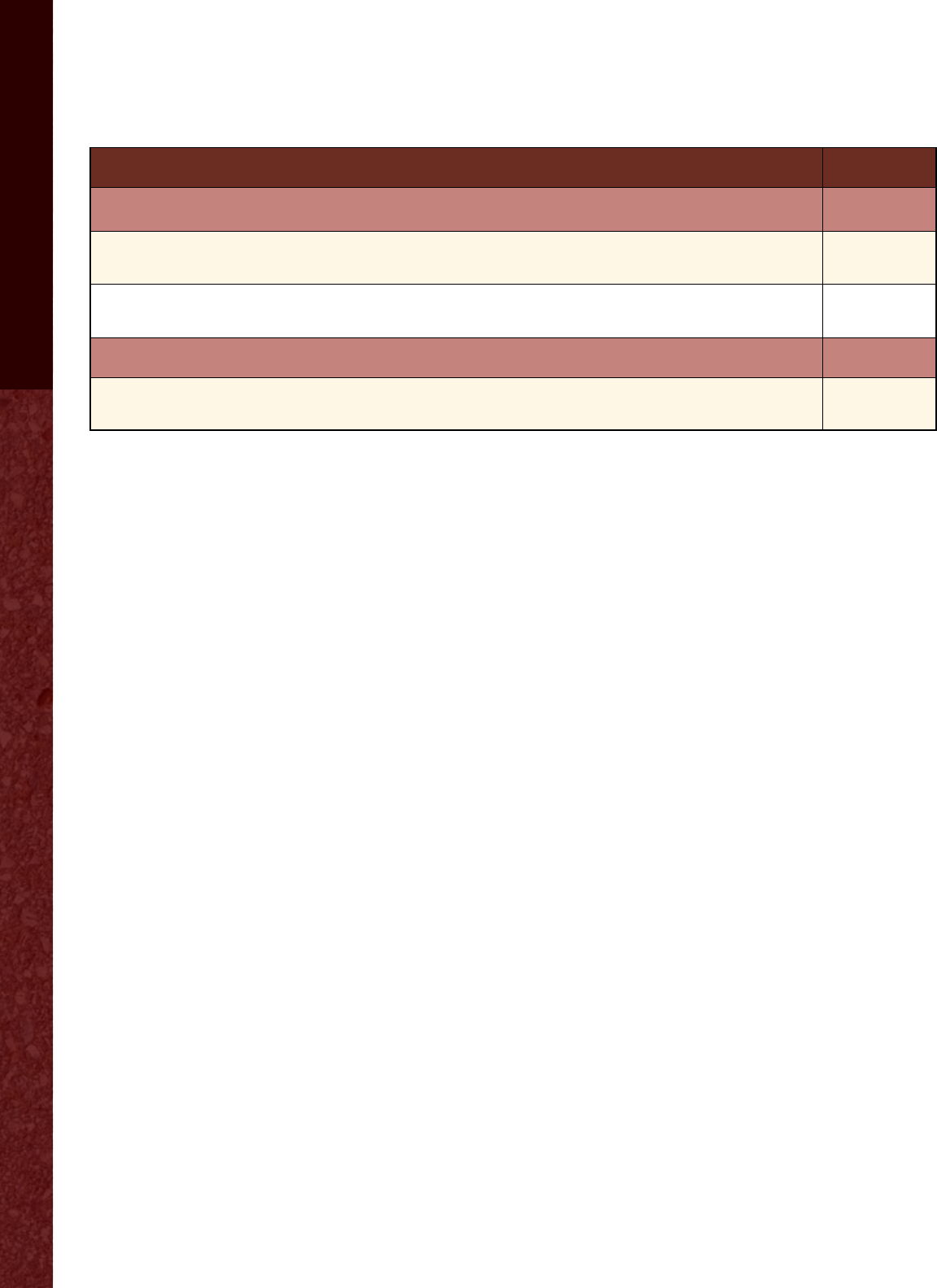

Risk Workshops

Risk workshops are formal meetings at which

agency sta, subject matter experts, and risk analy-

sis facilitators work together to identify and analyze

risks. Stakeholders from outside the agency can also

participate, if appropriate. The workshops can focus

on qualitative or quantitative risk analysis tech-

niques. Qualitative analyses typically identify and

rank risks. Quantitative analyses typically identify

risks, quantify uncertainty in performance (e.g., for

generating ranges of total cost and schedule), and

quantify the significance of each risk (e.g., for

subsequent risk management cost-benefit analysis).

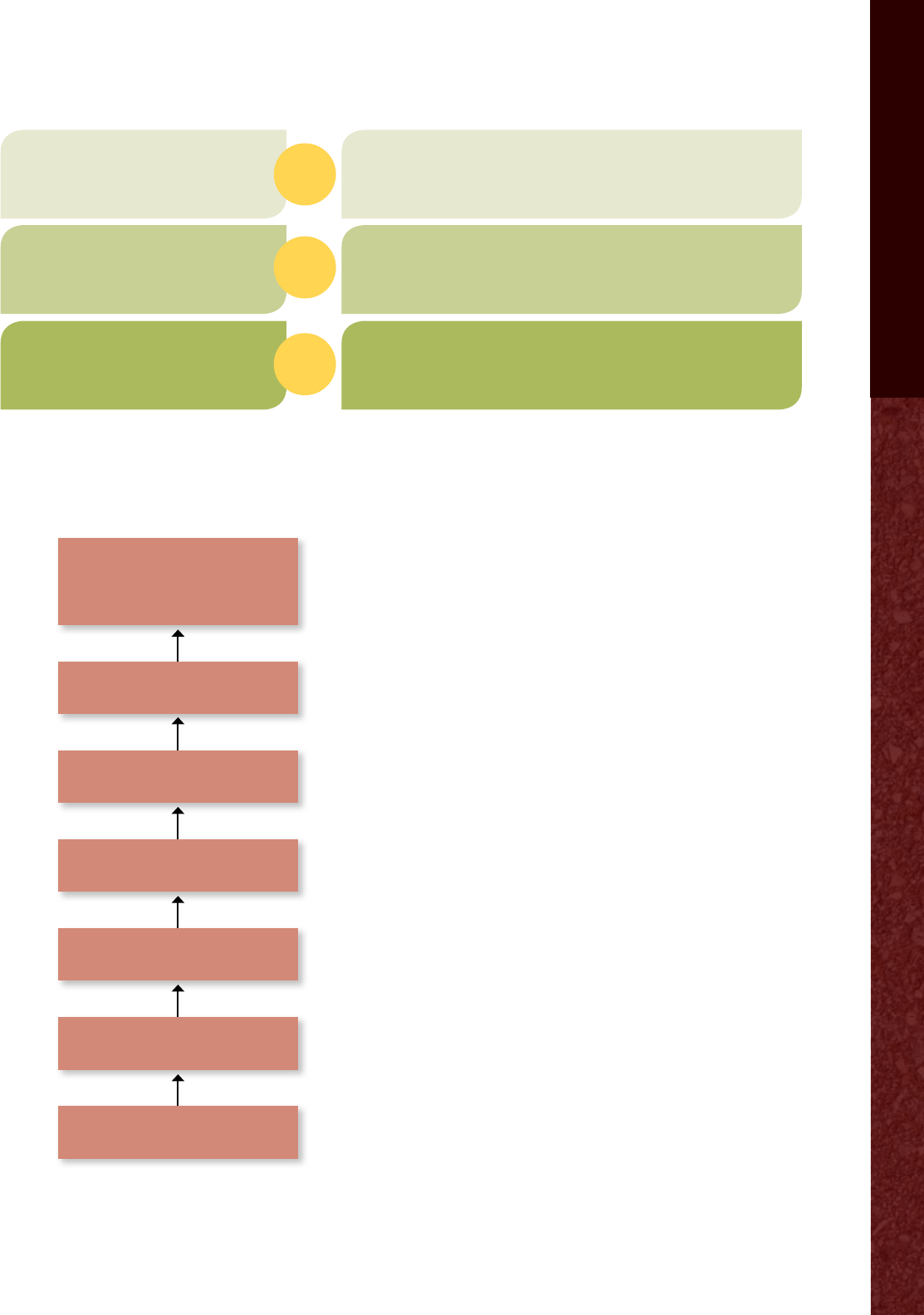

Figure 5 provides an example of a workshop

agenda and attendees. Risk workshops can vary in

length from a few hours to an entire week, depend-

ing on the outcomes desired. Workshops dealing

only with risk identification can typically be com-

pleted in a matter of hours. Workshops that result

in sophisticated financial or schedule simulation

models can last multiple days. A commonly cited

key to risk workshop success is finding the right

Figure 5. Generic risk workshop agenda and attendees.

1. Provide brief risk

identication training.

2. Dene scope and goals

of risk identication

workshop.

3. Discuss assumptions

and issues of risk.

4. Brainstorm risks.

5. Review historic check-

lists for any brainstorm-

ing oversights.

6. Summarize results.

• Risk Facilitator

• Project or Program

Manager

• Internal Subject Matter

Experts

• External Subject Matter

Experts

• Appropriate Internal

and External

Stakeholders

14 Chapter 2: Common Definitions, Strategies, and Tools for Risk Management

people to attend. Risk identification needs to come

from a variety of sources to be comprehensive, and

risk assessment should have a consensus input to

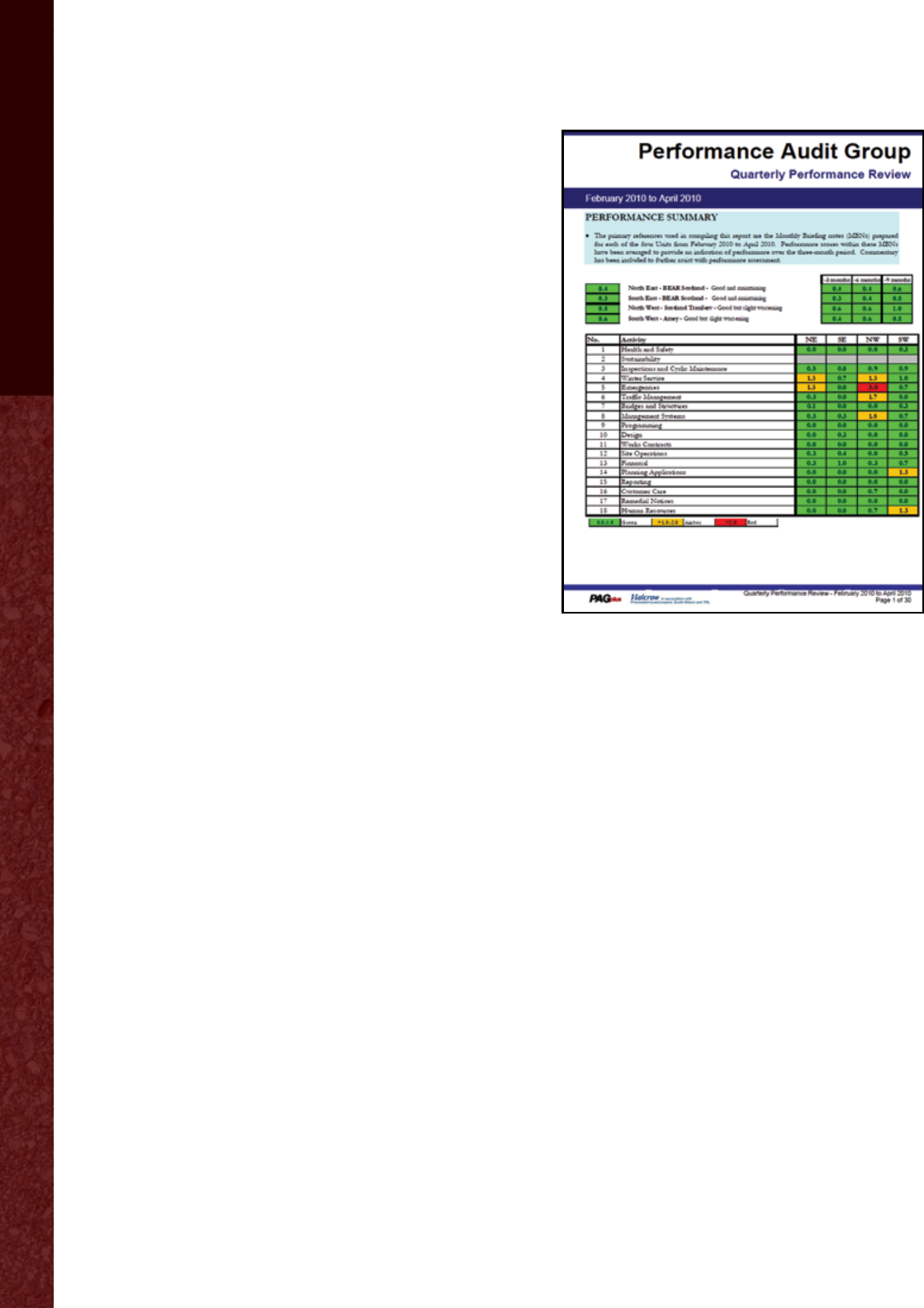

be accurate.

The products of risk workshops vary depending on

the complexity of the issues and time available for

the workshop. Common products from the least to

most complex are as follows:

A list of risks with complete descriptions

A quantification of risk for both consequence

and likelihood

A range of project costs and schedules to

support contingency estimates

Initial risk mitigation plans

Preliminary risk register and risk management

plan

In addition to these products, risk workshops

generally help align team members’ understanding

of objectives and risks and focus resources on the

areas that are most aected.

All agencies visited on this scan used risk work-

shops. Transport and Main Roads in Queensland,

Australia, used half-day risk workshops with its

board of directors to manage strategic risks. The

Highways Agency in England used risk workshops to

identify risks and rely on the experience and knowl-

edge of team members (and internal and external

stakeholders where appropriate).

12

Transport Scotland used risk workshops to identify

and quantify risks (see figure 6). Its workshops,

which use a proprietary system called GroupSys-

tems, were the most structured of all the examples

found on the scan. All workshop participants are

provided with a laptop computer to identify and

quantify risks anonymously. The agency has found

that the benefits include better brainstorming

because participants can debate and vote anony-

mously. The voting draws on the experience and

expertise of all participants, and the system helps

achieve consensus more rapidly and captures all

information automatically.

12

Highways Agency (2010). Highways Agency Risk

Management Policy and Guidance. Highways Agency,

London, England.

Risk workshops are a key tool in the risk manage-

ment process. Whether it be at the agency, program,

or project level, the use of workshops to gain input is

essential to the risk management process.

Risk Registers

A risk register is a tool that agencies use to address

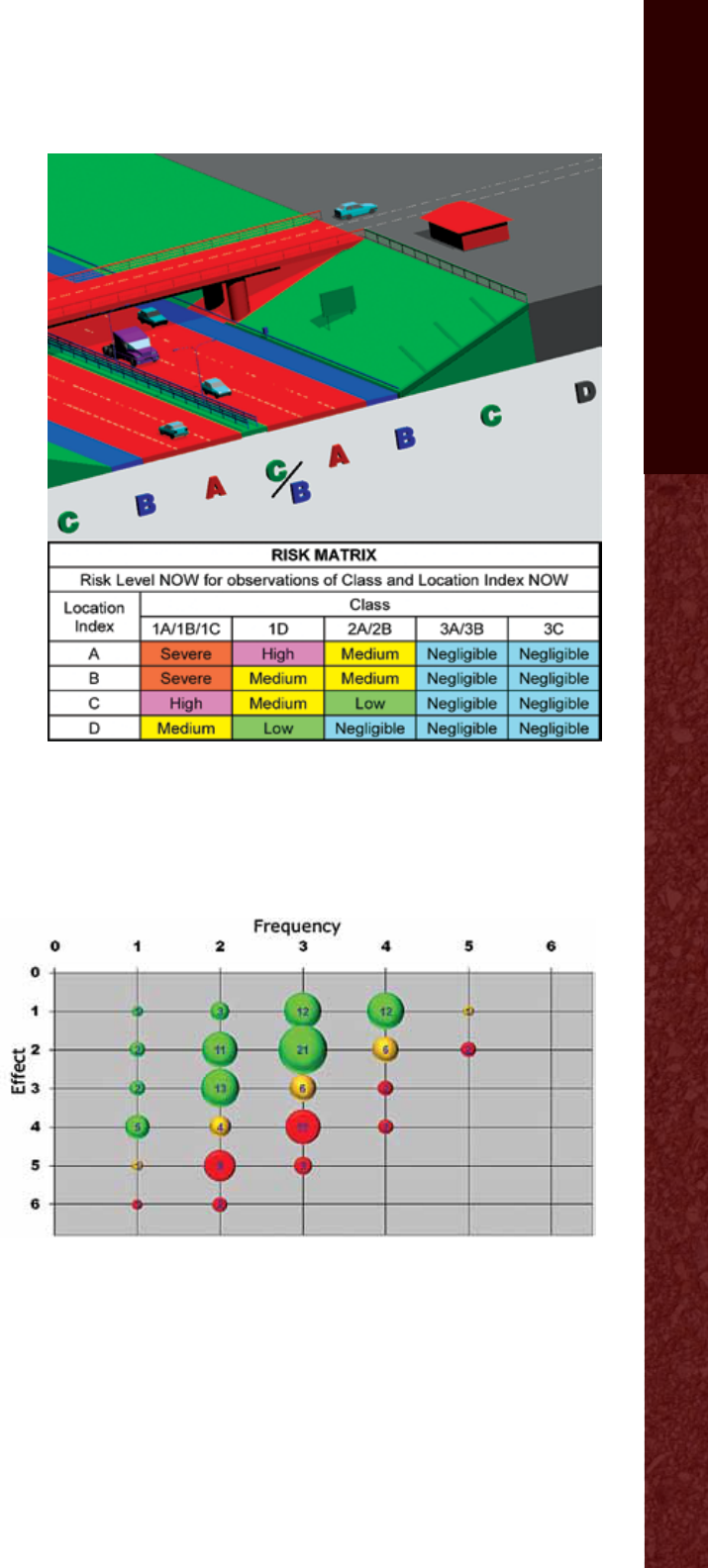

and document risks. They are often the product of

a risk workshop. The scan team found that the risk

register was the most common risk management

tool at all agencies. Figure 7 shows how Transport

and Main Roads in Queensland, Australia, applied

risk registers throughout the agency. The risk

register is a living document that describes risk

characteristics. For identified risks, the register

typically provides an assessment of the root

causes, the objectives aected (e.g., agency

goals, program performance measures, project

cost and/or schedule), an analysis of their likelihood

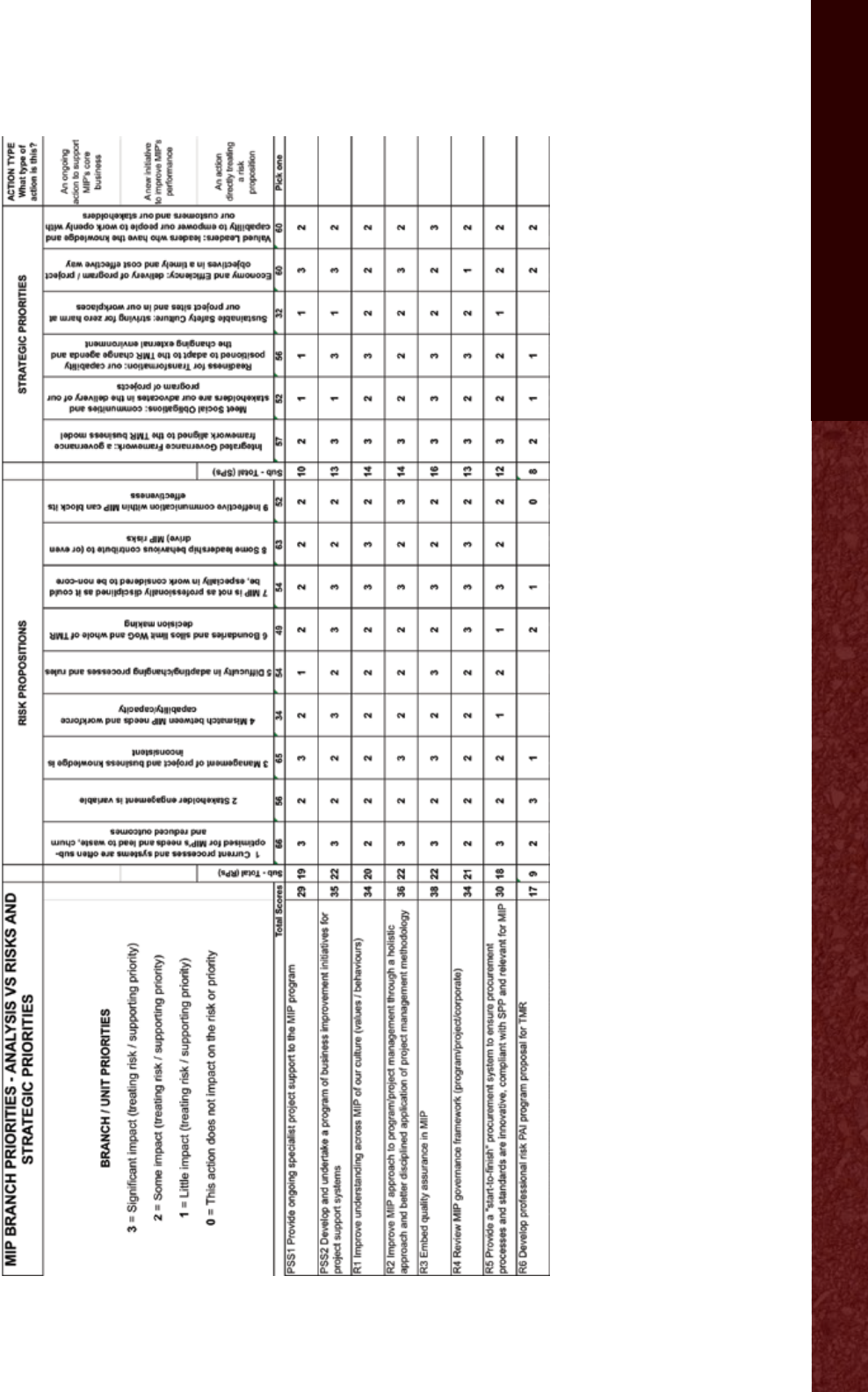

of occurring, their impact if they occurred, the

criteria used to make those assessments, and the

overall risk rating of each risk by objective. It can

include risk triggers, the response strategies for

high-priority risks, and the risk owner who will

monitor the risk. It is a comprehensive list of risks

and how they are being addressed as part of the

holistic risk management process. Although sophis-

ticated risk register software is commercially

available, the scan team found that risk registers

are generally kept on a spreadsheet that can be

easily categorized, updated, and maintained

throughout the agency.

A risk register is a living document. Transportation

executives update risk registers relating to their

strategic objectives in monthly or quarterly meet-

ings. Program managers update risk registers in

coordination with their asset management and

investment decisions. Project managers update their

risk registers as they progress through project

development and manage the cost, schedule, and

contingency budgets. There is no prescription for

how extensive a risk register should be. Based on

the scan team’s findings, the agency should deter-

mine the most beneficial use of the risk register, with

the objective of minimizing the impact of risks.

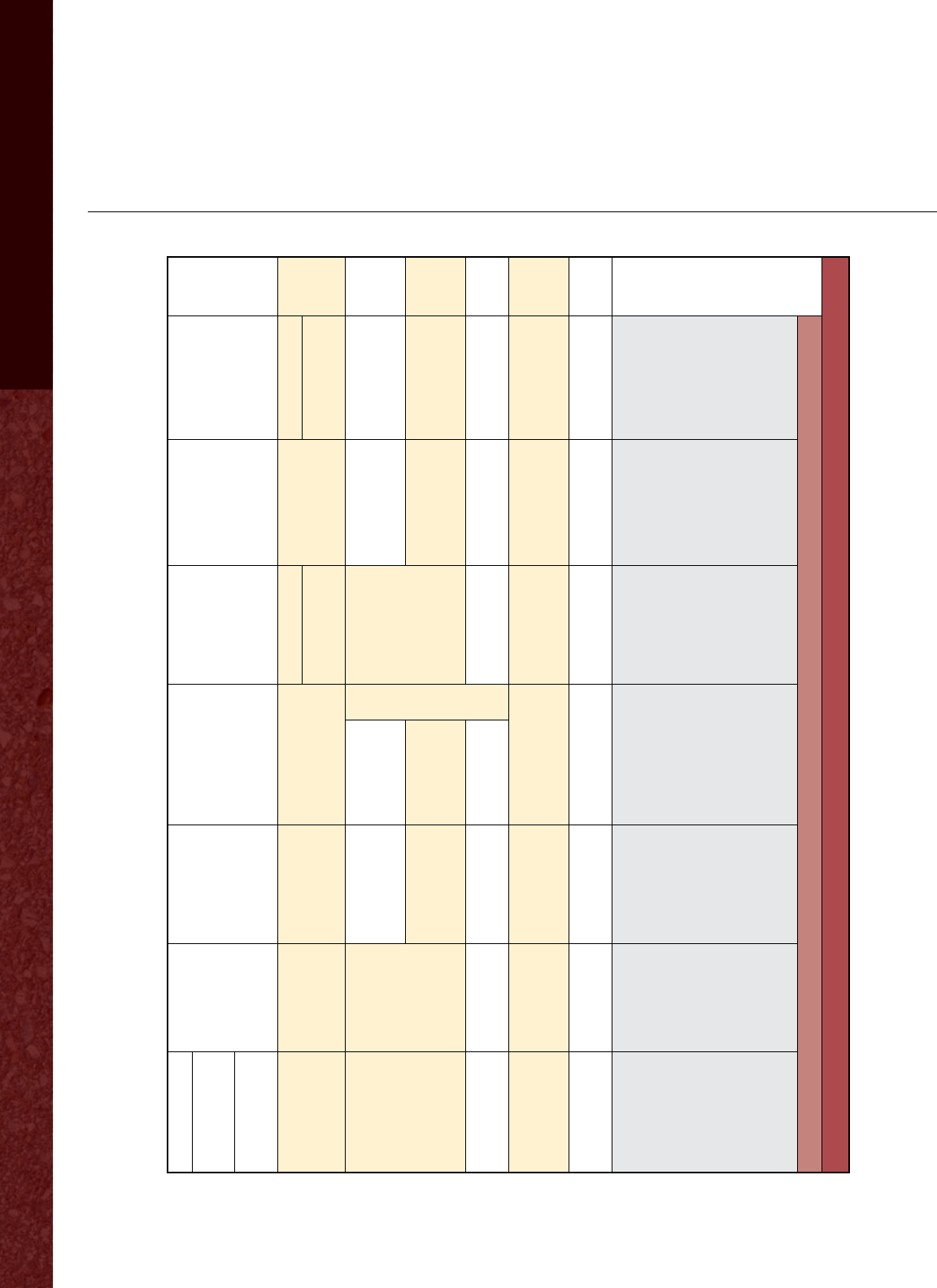

Figure 8 (see pages 16 and 17) provides an example

of a risk register template from VicRoads in Victoria,

Australia. The risk register covers the entire risk

management process. Risks are described in the first

column. The remaining columns describe important

Transportation Risk Management: International Practices for Program Development and Project Delivery 15

information about the risks relating to the manage-

ment process, including the following:

Key risk area

Reputation

Environment

Security of assets

Management eort

Legal and compliance

Health and safety of VicRoads

project activities

Business performance, scope, time,

and capability

Financial

Stakeholder management

Quality

Trac management

Risk reference

Potential cause (and assessment of

uncontrolled risk)

Existing risk controls, management actions,

and management tools

Risk assessment with existing controls

Consequence

Likelihood

Risk rating

Proposed further risk treatment actions

Action

Responsibility

Target completion

Risk assessment after treatment actions

Consequence

Likelihood

Risk rating

Progress report

Comment on progress

Responsible ocer

Revised forecast completion

The Highways Agency in England provided the scan

team with a copy of its risk register template (see

figure 9, page 18). The template contains fewer

details than the template from VicRoads, but it

provides similar information for each identified risk,

including the following:

Risk category

Risk reference

Gross risk status

Risk treatment

Controls in place

Control description

Lead for control action

Residual risk status

Planned further action

Lead for planned further action

Target risk level

Figure 6. Transport Scotland’s risk workshop.

Figure 7. Aligned risk management approach (Transport and

Main Roads, Australia).

16 Chapter 2: Common Definitions, Strategies, and Tools for Risk Management

Risk

Description

MPD Key

Risk Area

(Key Success

Factor)

Ref. Potential Cause

(and assessment of

Uncontrolled Risk)

Existing Risk Controls,

Management Actions

and Management Tools

Risk Assessment with

existing controls

Consequence Likelihood Risk

Rating

Identify and

describe

credible

events or

situations that

would impact

on the

achievement

of goals and

objectives.

Identify credible reasons

that the risk event might

occur. Consider credible

scenarios or potential

failures.

Make an informed

judgement of the likely

inherent risk without the

operation of existing

controls.

By considering the

inherent risk we are able

to prioritise and monitor

that the controls that

have been put in place

are working as intended.

Identify key policies,

management systems,

procedures, actions etc

that have been put in

place that will eliminate

or reduce the potential

consequences and/or

likelihood of the risk

event occurring.

Key controls should be

prioritised, monitored

and assessed to ensure

eectiveness in

reducing the uncon-

trolled risk level (e.g. by

audit or performance

monitoring)

Consider with

existing

controls in

place.

Consider

with

existing

controls in

place.

Assess risk

level with

existing

controls in

place.

Extreme

Division/Project—Consequences threaten the continuation of the

Business Area/Project and possibly major impact to the reputation of

VicRoads Major Projects Division requiring intervention from VicRoads

executive management—requires prompt action by Director Major

Projects to implement stringent new controls to treat the risk.

Key Risk Areas (Key Success Factors)

from MPD Project Risk Management

Assessment Guide

• Reputation

• Environment

• Security of Assets

• Management Eort

• Legal & Compliance

• Health & Safety of VicRoads Projects

activities*

• Business Performance, Scope, Time &

Capability

• Financial

• Stakeholder Management

• Quality

• Trac Management

High

Division/Project—Consequences threaten the eective completion of the

Business Area/Project—existing controls must be eective and requires

additional treatment action to be managed by Project Director level.

Medium

Project—Consequences threaten completion of a Business Area/Project

section or activity—existing controls must be eective and possibly

additional treatment action eectively implemented—action to be

managed at Project Delivery Manager level.

Low

Project—Risk is managed by current practices and procedures—conse-

quences are dealt with by routine operations at Team Leader level—moni-

tor routine practices and procedures for eectiveness.

Documentation is required to demonstrate that the typical

elements of risks in Attachment A have been considered. The

Corporate Risk Management Assessment Guide or MPD Project

Risk Management Assessment Guide should be used to deter-

mine the risk level and to determine if additional treatment action

is required.

MPD Risk Profile—Risk Register and Risk Management Plan